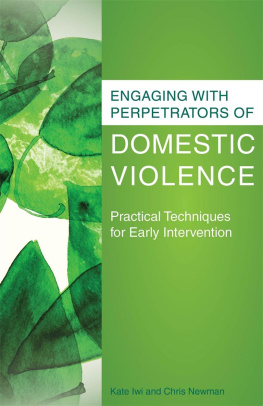

ENGAGING WITH PERPETRATORS OF

DOMESTIC VIOLENCE

by the same authors

Picking up the Pieces After Domestic Violence

A Practical Resource for Supporting Parenting Skills

Kate Iwi and Chris Newman

ISBN 978 1 84905 021 0

eISBN 978 0 85700 533 5

of related interest

Intimate Partner Sexual Violence

A Multidisciplinary Guide to Improving Services and Support for Survivors of Rape and Abuse

Edited by Louise McOrmond-Plummer, Patricia Easteal AM and Jennifer Y. Levy-Peck

Foreword by Raquel Kennedy Bergen

ISBN 978 1 84905 912 1

eISBN 978 0 85700 655 4

Changing Offending Behaviour

A Handbook of Practical Exercises and Photocopiable Resources for Promoting Positive Change

Clark Baim and Lydia Guthrie

Foreword by Fergus McNeill

ISBN 978 1 84905 511 6

eISBN 978 0 85700 928 9

Hearing Young People Talk About Witnessing Domestic Violence

Exploring Feelings, Coping Strategies and Pathways to Recovery

Susan Collis

Foreword by Gill Hague

ISBN 978 1 84905 378 5

eISBN 978 0 85700 735 3

Rebuilding Lives after Domestic Violence

Understanding Long-Term Outcomes

Hilary Abrahams

ISBN 978 1 84310 961 7

eISBN 978 0 85700 320 1

Talking to My Mum

A Picture Workbook for Workers, Mothers and Children Affected by Domestic Abuse

Cathy Humphreys, Ravi K. Thiara, Agnes Skamballis and Audrey Mullender

ISBN 978 1 84310 422 3

eISBN 978 1 84642 526 4

ENGAGING WITH PERPETRATORS OF

DOMESTIC

VIOLENCE

Practical Techniques for Early Intervention

KATE IWI AND CHRIS NEWMAN

Jessica Kingsley Publishers

London and Philadelphia

on pages 458 is reproduced from Calvin Bell with kind permission from Safer Families/Ahimsa.

The Risk Indicator Checklist on pages 557 is reproduced from CAADA with kind permission.

Information Sheet on p.143 is reproduced with kind permission from DVIP.

First published in 2015

by Jessica Kingsley Publishers

73 Collier Street

London N1 9BE, UK

and

400 Market Street, Suite 400

Philadelphia, PA 19106, USA

www.jkp.com

Copyright Kate Iwi and Chris Newman 2015

Front cover image source: Shutterstock. The cover image is for illustrative purposes only.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any material form (including photocopying of any pages other than those marked with a *, or storing it in any medium by electronic means and whether or not transiently or incidentally to some other use of this publication) without the written permission of the copyright owner except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of a licence issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd, Saffron House, 610 Kirby Street, London EC1N 8TS. Applications for the copyright owners written permission to reproduce any part of this publication should be addressed to the publisher.

Warning: The doing of an unauthorised act in relation to a copyright work may result in both a civil claim for damages and criminal prosecution.

All pages marked * may be photocopied for personal use with this programme, but may not be reproduced for any other purposes without the permission of the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978 1 84905 380 8

eISBN 978 0 85700 7384

CONTENTS

3.7: Conflict Resolution

INTRODUCTION

CHAPTER 1.1

Contextualising the Model

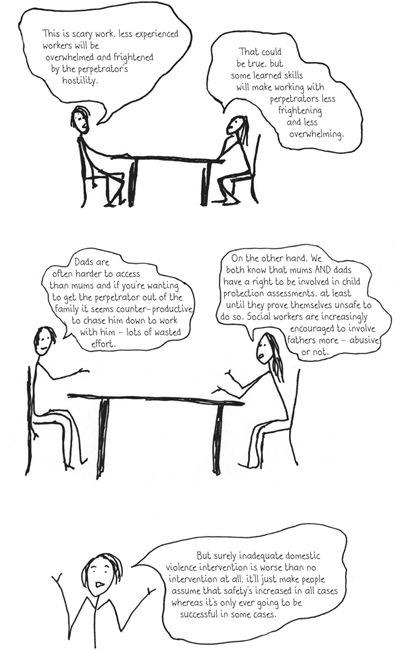

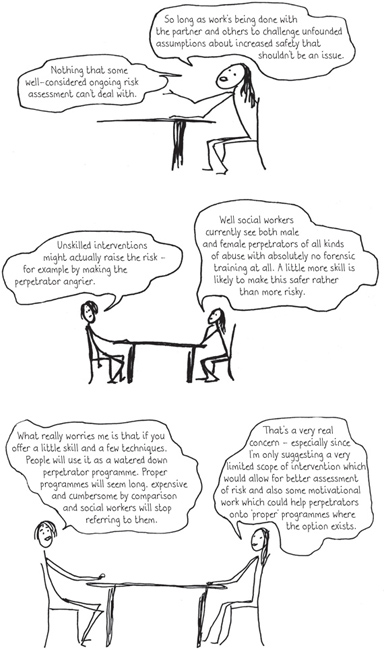

Child protection social workers and family support workers can today complete their training without learning a single thing about how to work with domestic violence perpetrators. Yet in case after case they are expected to do just that. This peculiar situation has arisen in part due to a controversy in the domestic violence (DV)1 field surrounding skilling up frontline professionals to work with perpetrators. The arguments on each side look something like this:

Despite all this, the benefits of skilling frontline workers to do this work remain compelling: in the absence of any work with the perpetrator, the onus falls upon the woman to undergo assessment and ultimately to change. She is the one that social workers and other professionals feel frustrated with and sometimes accusatory towards. She becomes the problem and is seen as failing to protect. Working with the perpetrator places the emphasis to change back on the person causing the problem.

But perhaps most importantly, a well-timed and well-placed intervention might genuinely make some people less risky and their children and (ex-)partners safer.

This book is primarily aimed at frontline practitioners like child protection social workers who want to engage with someone they suspect has been abusing an intimate partner. The exercises and techniques this handbook offers are aimed at helping them make the most of their limited client contact.

This handbook is not going to provide practitioners with a whole DV perpetrator programme. Accredited perpetrator programmes are long (24 weeks and upwards) and the research suggests that the resultant changes are deeper and more sustainable. There are lots of excellent perpetrator programmes out there at the back of this book we provide the details of Respect, a UK-based organisation whose role it is to signpost practitioners and abusers to whats on offer, both in terms of models and UK services. We are aware that recent changes to the England and Wales child protection system have set a strict 26-week deadline for care proceedings to finish. This is because delays to decision-making can have an adverse effect on outcomes for children. This change to the system also creates implicit pressure for quick fix interventions. Of course, pressure for shorter (and cheaper) interventions is not limited to England and Wales. Whilst it would be wonderful if we could find a brief intervention which reliably produced sustainable reductions in abuse and violence in the home, there is no evidence that such an intervention exists at the present time, and the exercises in this book are certainly not designed to serve that function though they can be used more positively, for treatment to be tested out before proceedings start.

The other thing this book is not is a guide to anger management, though it includes a couple of anger management techniques. This book is firmly directed at work with abuse in intimate relationships abuse thats usually about all sorts of expectations that people have of one another because theyre in an intimate relationship. Additionally, this book is not about anger per se which is just an emotion, and one the authors have no issue with its about abusive behaviour, which is a whole different ball game.

We very much hope that the techniques we are suggesting here will be delivered alongside some separate work with the victim of the abuse. That part of the intervention is probably going to be the best way to increase family safety. Whats more, theres always a danger that work with the perpetrator can mean that the victim feels relieved and reassured, but this may be unwarranted. A lot of women get back with partners or cancel plans to leave for a refuge when their abuser promises to get help. It could be that the abuser being worked with will prove impervious to these techniques and so its important to make sure that the victim is really clear that theres no guarantee of change. While somebody works with the abuser, somebody else (ideally not the same person that can get complicated) has to be encouraging the victim to continue assessing and planning for the safety of herself and the children.