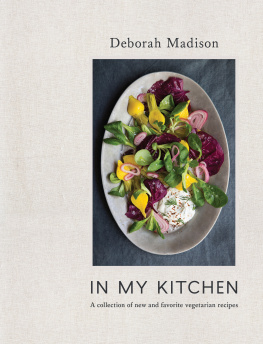

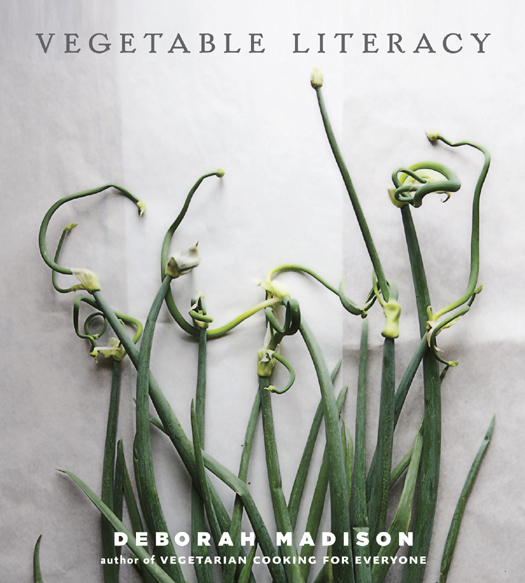

Copyright 2013 by Deborah Madison

Photographs copyright 2013 by Christopher Hirsheimer and Melissa Hamilton

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Ten Speed Press, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

www.crownpublishing.com

www.tenspeed.com

Ten Speed Press and the Ten Speed Press colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Madison, Deborah.

Cooking and Gardening with Twelve Families from the Edible Plant Kingdom, with over 300 Deliciously Simple Recipes Deborah Madison. First edition.

pages cm

1. Cooking (Vegetables) 2. Food cropsIdentification. I. Title.

TX801.M235 2013

641.65dc23

2012030968

eBook ISBN: 9781607741923

Hardcover ISBN: 9781607741916

v3.1

For Patrick and Dante, who make so much possible.

CONTENTS

RECIPES

INTRODUCTION

I T STARTED WITH a carrot that had gone on in its second year to make a beautiful lacy umbel of a flower. I was enchanted and began to notice other lacy flowers in my garden that looked similarparsley, fennel, cilantro, anise, as well as Queen Annes lace on a roadsidethey are all members of the same plant family, as it turned out. Similarly, small daisy-like flowers, whether blue, yellow, orange, enormous or very small, bloomed on lettuce that had gone to seed as well as on wild chicories, the Jerusalem artichokes, and, of course, the sunflowers themselves. Were they related? They were, it turns out. And did edible members of this group somehow share culinary characteristics as well? Often they did. That led me to ask, What are the plant families that provide us with the vegetables we eat often, what characteristics do their members share, and what are their stories?

When we look closely at the plants we eat and begin to discern their similarities, that intelligence comes with us into the kitchen and articulates our cooking in a new way. Suddenly our raw materials make sense. We can see how we might substitute related vegetables when cooking, or how all the umbellifer herbs, including cilantro, parsley, and chervil, flatter umbellifer vegetables, such as carrots and fennel. And when we encounter plants with all their leaves, roots, and maybe even flowers intact, we can observe the shapes of leaves, the patterns of petals, the changing forms as they progress from their first true leaves to the perfect stage for eating to maturity and, finally, their going to seed. Curiously, we might discover that broccoli leaves and stalks are quite edible, or that a neglected leek makes the same flower as a chive when it finally blooms. Bringing plants features into view can free us as cooks, make us unafraid to use some amaranth thats going full guns in the garden in place of spinach, which has bolted and dried up. They are, after all, related.

I began to cook as a teenager. But as for growing something, that was another story. My botanist father could pick up a plant that caught his eye from a neighbors trash pile, put in the ground, and walk away and it would grow, just like that. He had ten green fingers and we had a lot of interesting plants in our garden, many of them edible. Despite his example, it didnt occur to me to plant anything until I was in my mid-thirties and living at Green Gulch Farm. My then husband, Dan, and I lived in a cabin that had been fashioned from a shed that had housed two prize Hereford bulls (though not at the same time). The yard area, such as it was, was mud when it rained and clay when it dried. It had been trampled upon for years by creatures weighing over a ton. I looked at this sad ground with nothing growing in it and thats when I got the idea to plant something. I sought out Wendy Johnson, Green Gulchs head gardener, who gave me a tiny sage plant. When shovel and fork failed to penetrate the compacted soil, I went back to her for a pickaxe. Once the sage plant was safely embedded in its little niche, I was hooked. All I could think about was plants and gardens, and how to design mine.

One Sunday Dan and I went to a nursery that was said to be especially interesting. Called Western Hills, it was tucked back in the lush folds of Sonoma County. As we entered we were handed glasses of champagne for it turned out that Western Hills was celebrating a birthday. But the way a dog never forgets the storefront that harbors a stash of canine treats, for many years I harbored the vague expectation that I would always be handed a glass of champagne when I went to a nursery. Plants had, it seemed, become an occasion for celebration.

In spare hours and minutes, over a period of five years, I did eventually make a garden with mounds of ceanothus, a screen of tall rosemary along the front, old roses, a stellar crab apple, unusual flowers and grasses. Twenty years later I was a farmers market advocate, a market manager, and a faithful shopper. One day I looked at some beans and thought, I could grow those! And I started a garden in New Mexico.

Growing vegetables was exciting. I could harvest what I grew, I could cook it, share it, and watch my plants do whatever it is they were prone to do. I could also plant odd things like salsify, cardoons, black-eyed peas, and heirloom varieties of plants from the Seed Savers Exchange, like Rat Tailed radishes and Sultans Crescent beans, vegetables I couldnt find elsewhere.

As I worked in the garden I began to notice how plants moved through their cycles. I experimented using them in different stages, like chard that had bolted, or the tiniest of thinnings. Where plants had been allowed to stay long enough to drop their seeds I saw that the following spring they were up weeks before the planting dates on seed packages. I learned to recognize the first leaves, the cotyledons, which is very useful if you want to know whats coming up and whether or not to pull it out. Elm trees you want to extract; larkspur stays. I saw that if you dont mess with your soil too much and you leave the fall leaves in place, all kinds of things will come up that you hadnt known would. Mostly I learned that despite the all the excellent books on gardening, the garden cant help but teach you about itself. It tells you when to leave it alone, that the flea beetles will leave at a certain point, and, at least where I live, that there will always be squash bugs. It tells you that there is no point in planting seeds in cold soil, even if the days are warmer than usual; you might as well wait. You begin to notice areas of sun and shade, the heat reflected off of adobe walls, what plants like it, what plants dont. You start to observe what thrives, and what doesnt; what the gophers feast on and what they ignore. Ive learned that five eggplant plants are too much for two people, but that five shishito plants are not because I like having a mass of them at a time. Ive seen that not every year is the same. Some years are tough, other years the garden seems to flourish with ease. I work just as hard in both cases. I think it could take forever to learn my garden. I suspect that it will.