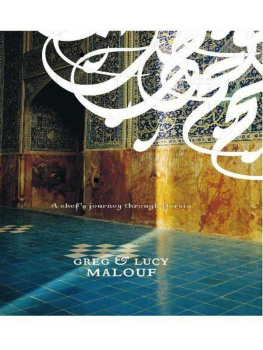

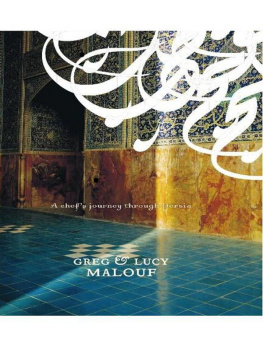

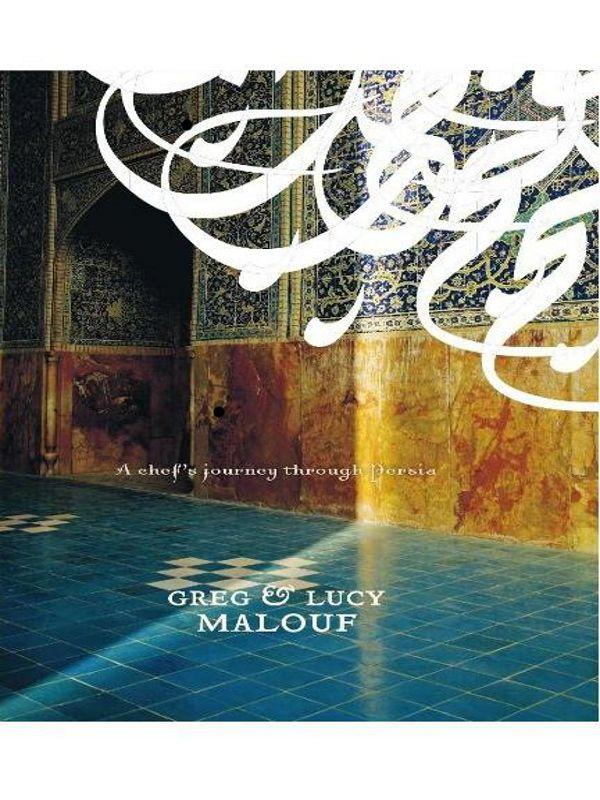

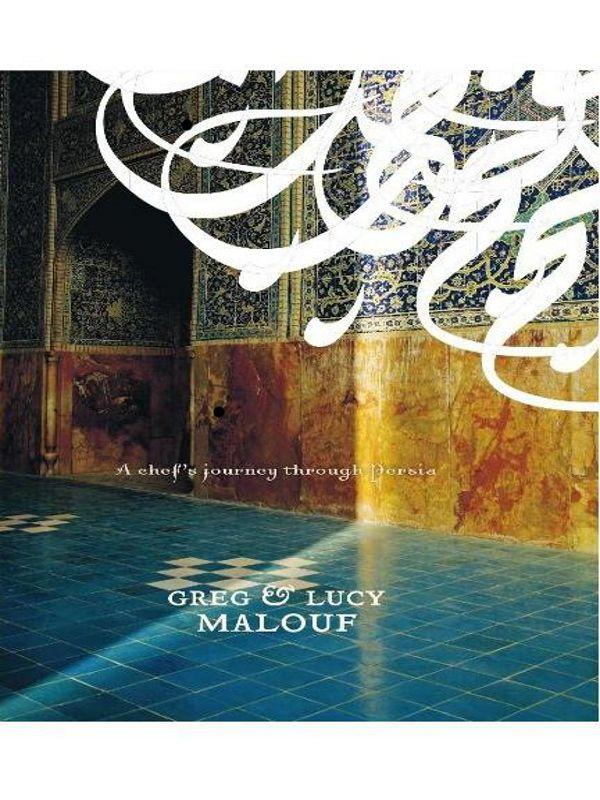

GREG & LUCY

MALOUF

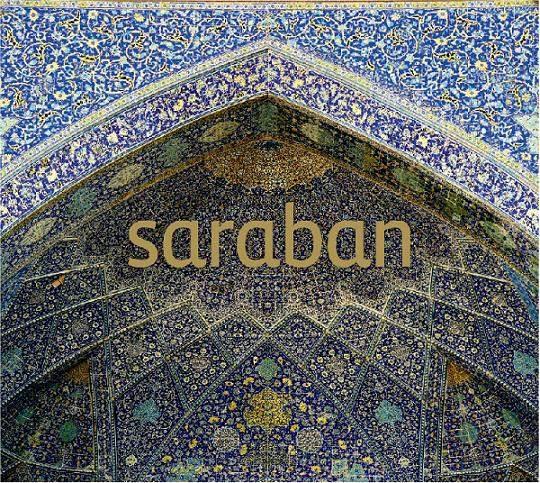

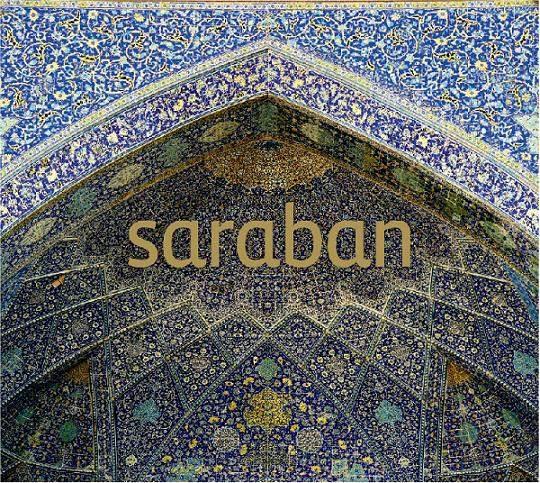

Saraban

A chefs journey through Persia

PHOTOGRAPHY BY

Ebrahim Khadem Bayat and Mark Roper

Published in 2010 by Hardie Grant Books

Hardie Grant Books (Australia)

85 High Street

Prahran, Victoria 3181

www.hardiegrant.com.au

Hardie Grant Books (UK)

Second Floor, North Suite

Dudley House

Southhampton Street

London WC2E 7HF

www.hardiegrant.co.uk

Designer: Sandy Cull, gogoGingko

Editor: Caroline Pizzey

Photographer (location pics): Ebrahim Khadem Bayat

Photographer (recipe pics): Mark Roper

Stylist: Glen Proebstel

Typesetter: J&M Typesetting

Map: Sandy Cull, gogoGingko

Cataloguing-in-Publication data is available from the National Library of Australia.

ISBN 978 174066 8 620

Colour reproduction by Splitting Image Colour Studio

Printed and bound in China by C&C Offset Printing

Copyright text Greg Malouf and Lucy Malouf

Location photography Hardie Grant Books

Food photography Mark Roper

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publishers and copyright holders.

In loving memory of May Malouf, 19322010

Contents

W e arrive in the early afternoon, when the sun is at its hottest. After the long, dusty drive we are beginning to understand a little of how it must have felt in the old caravan days, to be part of a camel train moving slowly across the burning desert, with only the low silhouette of distant mountains to hold the eye and the shimmering promise of a far-off oasis to rekindle hope in the heart.

/

We park our car at the edge of the old city and trudge through the sun-baked alleyways to the hotel our modern-day caravanserai. The ancient wooden door is embedded in a thick mud-brick wall that reveals nothing of what lies within. We push it open and pass through a cool vestibule into a courtyard garden.

/

The hotel is far from luxurious, but on this stifling afternoon it offers a welcome glimpse of Old Persia. The rooms are arranged traditionally around a central courtyard. There are tall trees, colourful flowers and a long pool lined with bright-turquoise tiles. Here is all the promise of paradise: the sound of tinkling water, cool shade that beckons, and rest and refreshment to be enjoyed on low, cushioned daybeds. A young man appears from nowhere bearing a tray of ice-cold watermelon and tall frosted glasses of pomegranate juice. All is languid pleasure, delight upon delight. Within minutes our senses are revived, our good humour restored, and the welcome break in our journey gives us time to pause and reflect.

/

If truth be told, we were singularly unprepared for this Iran. Despite the many months of research and planning, nothing we had read or heard or seen of the countrys recent history had suggested that there was anything left here of the old caravanserai romance. In fact it was exceedingly difficult to put together any convincing picture of the place at all. Like the shifting mirage of a desert oasis, Iran itself proved elusive and enigmatic. It often seemed as if the real country whatever that might be had dissolved like day into night after the 1979 revolution. Since then, the only perspective that the rest of the world has had is one reflected through a prism of anti-Islamic hostility, particularly in the West, where the very name Iran is weighed down with negative connotations: at best it is seen as mysterious, secretive, baffling; at worst it is a dark, frightening place full of dark, frightening people, geopolitically menacing and religiously intolerant.

/

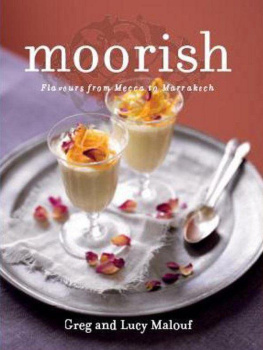

It is certainly not at the top of many lists as a must-do travel destination, and for months before our departure people had been asking us, Why Iran?. That question, at least, was easy to answer. In our previous books we have explored other cuisines of the Middle East: the Arabian food of Lebanon and Syria, the Ottoman and Anatolian food of Turkey, and the Moorish food of North Africa. And there is no doubt that Persian food is the other great cuisine of the region. There are a number of impressively researched and inspiring cookbooks about traditional Persian food, and we knew from our reading that it is one of the most sophisticated, elaborate and complex food cultures in the world. But unless you live in a city with a flourishing Iranian population (and the diaspora is surprisingly far-flung), there are remarkably few opportunities to eat Persian food. Most Westerners, if they give it any thought at all, would most likely lump it in the general Middle Eastern basket of kebabs and rice and baklava.

/

But we were certain that there was much, much more than this to discover. In the end it seemed that there would be no way around it: if we really wanted to find out about Persian food we would have to go to Iran.

/

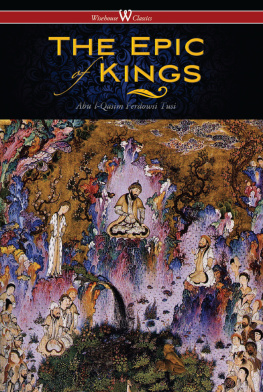

Iran or Persia? This proved to be the first of many conundrums, with each name conjuring up different, contradictory images. To many Westerners, Iran is the dour, puritanical place of the present day, while Persia is a romantic world of the distant past: of Scheherazade spinning her tales of one thousand and one nights; of fluffy cats, exquisite miniature paintings and gorgeous carpets; of roses and nightingales; of Omar Khayyams Rubaiyat , and of caravan trails along the ancient Silk Road.

/

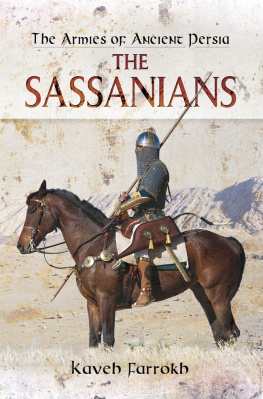

There is an element of truth and exaggeration in each version, but they are, of course, one and the same place. For most of its history, Iran has been known outside its borders as Persia, a corruption of the Greek name Persis, and it only became Iran in 1935 when Reza Shah Pahlavi declared it to be the countrys official name. To Iranians, however, their country has been known as Iran, the land of the Aryans, since the first millennium BC, when Indo-European tribes began to settle on the Iranian plateau.

/

Today Iran and Persia are used seemingly interchangeably although sometimes with subtle political reasons and we soon found ourselves quite happily using both, too. For this book we made the decision not to agonise over political or historical correctness, or how and when to use each, so in the pages that follow youll find both, which seems somehow quite in keeping with the duality of life in this complicated land.

/

This duality, these contrasts, the opaqueness once we arrived in Iran, we realised that they all contribute to a very real sense of mystery, and of reward. In this ever-contracting and connected world it often seems there are few things left that are strange and new. But as it turned out, this sense of being explorers in an unknown land was one of the most thrilling aspects of our journey around Iran. It felt as if we were being spun back to the days when travel was still an adventure, as if we were seeing places and things about which others from our world knew little.

Next page