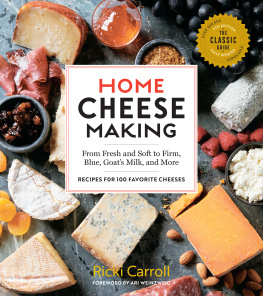

Text excerpted from Home Cheese Making by Ricki Carroll (Storey, 2002)

The mission of Storey Publishing is to serve our customers by

publishing practical information that encourages

personal independence in harmony with the environment.

Edited by Nancy W. Ringer and Carey L. Boucher

Cover design by Carol J. Jessop (Black Trout Design)

Illustrations by Elayne Sears

Text production by Jennifer Jepson Smith

2003 by Ricki Carroll

All rights reserved. No part of this bulletin may be reproduced without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages or reproduce illustrations in a review with appropriate credits; nor may any part of this bulletin be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or other without written permission from the publisher.

The information in this bulletin is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. All recommendations are made without guarantee on the part of the author or Storey Publishing. The author and publisher disclaim any liability in connection with the use of this information. For additional information please contact Storey Publishing, 210 MASS MoCA Way, North Adams, MA 01247.

Storey books and bulletins are available for special premium and promotional uses and for customized editions. For further information, please call 1-800-793-9396.

Printed in the United States by Excelsior

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Carroll, Ricki.

Making cheese, butter, & yogurt / by Ricki Carroll.

p. cm. (A Storey country wisdom bulletin; A-283)

ISBN 978-1-58017-879-2 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Cheese. 2. CheeseVarieties. 3. Butter. 4. Yogurt. I. Title.

II. Series.

SF271.C39 2003

637dc21

2003012691

CONTENTS

CHEESE is one of the earliest foods made that is still consumed by people. It dates back to at least 9000 B.C.E . Cheese making was important to the ancient Greeks, whose deity Aristaios was considered the giver of cheese. Homer sang of cheese in the Odyssey. And Greek Olympic athletes trained on a diet consisting mostly of cheese. Both yogurt and butter date back to at least 2000 B.C.E . and were historically regarded as foods of the gods.

The arts of making cheese, butter, and yogurt have been refined, but not substantially changed, over the centuries. The recipes in this bulletin help keep alive the pleasures of these processes, encouraging a holistic approach and a connection with the environment. Remember, cleanliness is of the utmost importance when dealing with milk, so follow these instructions carefully. Start with the soft cheeses () and advance to the rest later they will take more time and patience. Most of all, have fun.

The Ingredients

Most cheese-making ingredients can be purchased from cheese-making supply houses. You can buy milk, of course, at the grocery store. In the right hands, these ingredients can be turned into gastronomic delights.

Milk

Milk is a complicated substance. About seven-eighths of it is water. The rest is made up of proteins, minerals, milk sugar (lactose), milk fat (butterfat), vitamins, and trace elements. Collectively, these components are called milk solids. When we make cheese, we cause the protein part of the milk solids, called casein, to coagulate (curdle) and produce curd. At first, the curd is a soft, solid gel, because it contains all the water along with the solids. But as it is heated, and as time passes, the curd releases liquid (whey), condensing more and more until it becomes cheese. Most of the milk fat remains in the curd. Time, temperature, and a variety of friendly bacteria determine the flavor and texture of each type of cheese.

When making the cheeses in this bulletin, you can use whatever milk is available in your area. Store-bought milk will work fine, and you can even use dried milk powder for making any of the soft cheeses, as well as butter and yogurt. But no matter what type of milk you use, it must be of the highest quality. Always use the freshest milk possible. If it comes from the supermarket, do not open the container until you are ready to start making cheese.

Milk Yields

One gallon of milk yields about 1 pound of hard cheese or 2 pounds of soft cheese. The yield will vary slightly from milk to milk. The yield from goats milk and from nonfat milk is lower than that of cows milk, and the yield from sheeps milk is higher.

Now lets address the different types of milk, because the kind you end up working with may have an effect on the cheese-making process.

Cows milk. In the United States today, cows milk is the most popular for use in cheese making. This is not the case in the rest of the world, however, as goats and sheep feed the majority of the globes population. Yet cows milk is abundant, its curd is firm and easy to work with, and it produces many wonderful cheeses.

Goats milk is more digestible, more acidic, ripens faster, and needs less rennet than cows milk. It also produces a whiter and slightly softer cheese. When using it to make hard cheese, use calcium chloride and lower the temperature two to five degrees during the renneting process, because the curd tends to be delicate.

Sheeps milk is high in protein and vitamins and produces a very high cheese yield almost 2 times what you would expect from cows or goats milk. Use three to five times less rennet than you would for cows milk and top-stir carefully. Cut the curd into larger cubes and take thicker slices when ladling to preserve moisture. Use half of the required salt and press lightly. If necessary, add water to the curds at the cooking stage to help them float.

Raw milk comes directly from an animal and is filtered and cooled before use. It is not pasteurized, so it has a high vitamin content and rich flavor. It might also contain pathogens that can produce diseases such as tuberculosis, brucellosis, and salmonellosis.

If you use raw milk to make cheese that is aged fewer than 60 days (this includes most fresh cheeses), you must consult a veterinarian to be absolutely sure that there are no pathogens in the milk. Never use raw milk from an animal that is suffering from mastitis (inflammation of the udder) or receiving antibiotics. As a rule, if in doubt, pasteurize.

Homogenized milk produces a curd that is smoother and less firm than that of raw milk, so I recommend adding calcium chloride when using homogenized milk for cheese making. Homogenized milk may require up to twice as much rennet as does raw milk.

Pasteurized milk. In effect, pasteurization kills all bacteria, which is why you add a bacterial starter to pasteurized milk for most cheese recipes. Pasteurization also makes proteins, vitamins, and milk sugars less accessible to the body.

Ultrapasteurized milk keeps a long time unopened, but the protein in it is completely denatured, so you may as well drink water. You must use calcium chloride in ultrapasteurized milk. Do not use ultrapasteurized milk to make 30-Minute Mozzarella (see ).

How to Pasteurize Milk

If you acquire milk from a cow or a goat and need to pasteurize it, follow this simple procedure.

Pour the raw milk into a stainless-steel or glass pot and place the pot inside another, larger pot containing hot water. Put this makeshift double boiler on the stovetop.

Heat the milk to 145F, stirring occasionally to ensure even heating. Hold the temperature at 145F for exactly 30 minutes. The temperature and time are important. Too little heat or too short a holding time may not destroy all the pathogens. Too much heat or too long a holding time can destroy the milk protein and result in a curd that is too soft for cheese making.