PUBLISHED BY RANDOM HOUSE CANADA

Copyright 2013 Carolyn Abraham

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Published in 2013 by Random House Canada, a division of Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Distributed in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited.

www.randomhouse.ca

Random House Canada and colophon are registered trademarks.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Abraham, Carolyn

The jugglers children: a journey into family, legend and the genes that bind us / Carolyn Abraham.

Includes bibliographical references.

eISBN: 978-0-307-37215-4

1. Abraham, CarolynFamily. 2. Abraham family. 3. Genetic genealogy.

4. GenesPopular works. 5. Genetic disordersPopular works. I. Title.

QH 447. A 26 2013 929.20971 C 2009-906626-2

Cover design by Jennifer Lum

Cover images: Comstock / Getty images; Karinabak | Dreamstime.com;

Ekychan | Dreamstime.com; Luceluceluce | Dreamstime.com

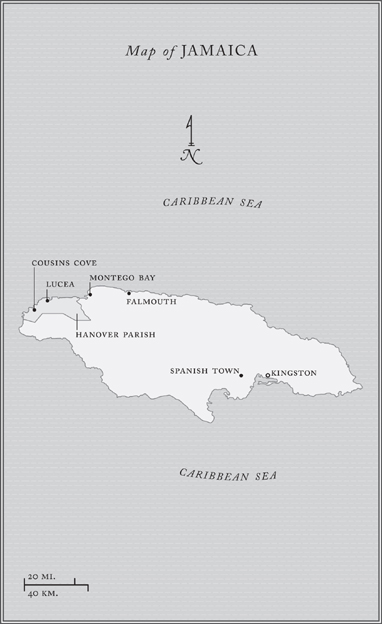

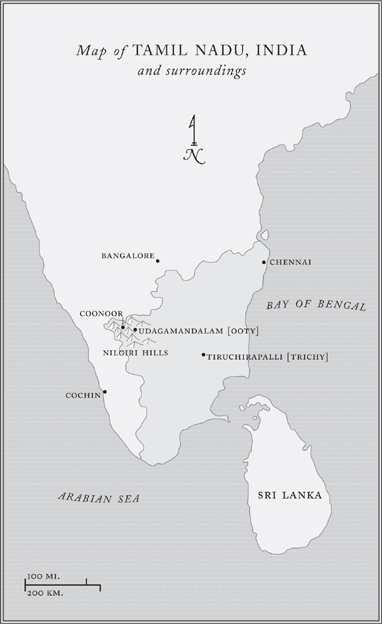

Maps: Paul Dotey

Interior images: All photos are property of the author.

v3.1

For Jade and for Jackson,

my x and y, my moon and sun

CONTENTS

If you cannot get rid of the family skeleton,

you may as well make it dance.

George Bernard Shaw, Immaturity

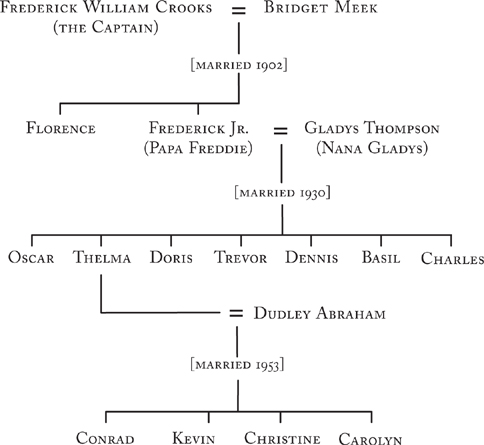

CROOKS FAMILY TREE

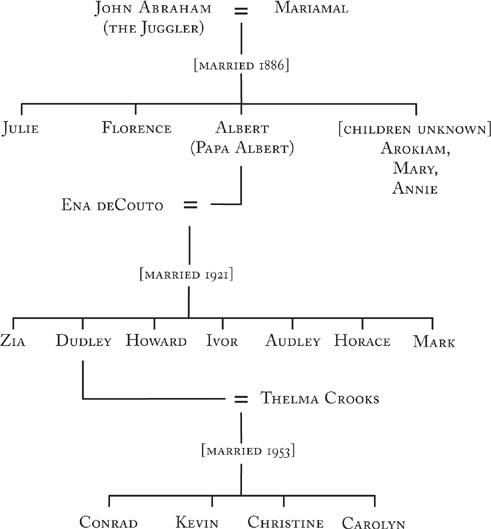

ABRAHAM FAMILY TREE

PROLOGUE

T here is a picture of my daughter taken about forty-eight hours after she was born. Shes propped up against pillows in our hospital room, pinched and scrawny, as newborns can be when they come early. Her eyes are half open, taking in the outlines of her new world, oblivious to the questions she pushed to the forefront of my mind in those first days of her life.

On her head is something that looks like a bonnet. Its white, shaped like a dome, and even has an elastic strap that stretches under her chin. If you look closely you can see its not a bonnet, but a mask, a regulation issue N-95, touted to keep out 95 percent of airborne particlesdust, pollution, viruses. In the spring of 2003 masks were as common as streetcars in our city. The hospital provided them to keep people from catching or spreading infection to others. But aside from a few doctors with masks of their own, and nurses in biohazard suits, there were no others. My husband and I never put the mask over her face while we were in that room.

Ten years later, if I try to pinpoint when the desire to know became the determination to find out, or why my daughter would know about DNA before she knew how to read, or how I became preoccupied with collecting it, from both the living and the dead, I keep returning to that picture. The birth of any child pushes the past into the present. It just so happened that Jade was born into a time and place where the clocks seemed to have stopped. An unexpected gift of time had come with her arrivalsix long days we spent under quarantine when the city had gone half-mad with fear and confusion.

A strange pneumonia had broken out that winter, a new viral disease called severe acute respiratory syndrome ( SARS ). Worldwide it infected more than eight thousand people and killed more than nine hundred. Forty-four died in Toronto. As a science reporter, I was writing about it for the Globe and Mail, and there was a lot to write. Ten thousand people were confined to their homes. Schools were closed. Conventions were cancelled. People stopped riding the subway and shaking hands, even in church.

For three months I chased the story, until the hot afternoon of June 5, when I became part of it. Eight months pregnant, I was at a meeting in a downtown coffee shop when my nose started to bleed heavily. I hailed a cab to the hospital, where nurses hooked up a fetal monitor, took a blood pressure reading and told me to call my husband.

My pressure is through the roof, I told Stephen. Theyre going to induce. Can you stop at the house and pack an overnight case?

He arrived with a hockey bag stuffed full of nearly everything wed bought or been given for our unborn child: washcloths, rattles, baby-safe detergent, a snowsuit sized for a three-year-old. It was just as well; we had to stay much longer than we expected.

A medical student working on the maternity ward developed the symptoms of SARS the day I was admitted. Anyone who had had contact with him was placed under strict ten-day quarantine. Women about to deliver would have to do so in a skeleton-staffed ward closed off from the rest of the world. That included me.

By nightfall of the following day, as the induction drugs took effect, I paced out my labour in a long, eerie corridor, quiet and dark except for the red glow of the exit signs. When the time came, Stephen had to run around the ward just to find a nurse.

Our daughter arrived before dawn, healthy and screaming, and just like that, the rapid pulse of our lives slowed. Alone in a double room with nowhere to go and no one to see, we snatched sleep at odd hours, fired N-95s across the room like slingshots, and took photoslots of photos.

She was the first baby in our family in more than a dozen years. Since no one could visit, everyone called. They asked the questions people do when a new life appears: What does she look like? Who does she look like?

She might have been fair and blue-eyed, like Stephens side, with hair of gold or red, or darker, like me. On my side the possibilities were wide and endless: a complexion of white or deep brown or anything in between. Her hair could have been smooth as black silk or coiled into springs too tight for a comb. She might have been a living testament to the ancestors whose stories had captivated me since I was a child, stories that inspired her name. We called her Jade, after Chinas imperial gem, beautiful and strong as an axe-head.

I wished my mums mother had lived to see her. I used to tell my grandmother about my work, the stories I was writing, the trips I took. She would lean in and whisper, But what about babies, my girl? When are you going to have babies? Oh, eventually, Id say and shrug. But there was always another story and new jobs and newspapers, and then one July morning in 1999 my mother called to tell me my grandmother had died.

I saw her before her body was taken away. Nana Gladys was still in her bed, the silver hair she curled meticulously lying in strings on her pillow, her mouth turned down in a grimace that reminded me of the expression shed wear if we were late picking her up.