Realizing the Dream Of Owning a Place In the Country

With careful planning and a modest investment almost anyone can turn the dream of owning a small farm or a few acres of country land into a reality. And with some effort this land may provide a significant portion of lifes amenities: wood for the fireplace, fresh produce for the table, a pond for fishing or swimmingeven waterpower to generate electricity. But as with any other major purchase, care and caution are required.

The first step is to have, in general terms, a strong notion of what it is you want. Those desiring year-round warmth will obviously have different priorities than those who wish to see the seasons change. Prospective part-time farmers will look for one kind of land, whereas weekend sojourners will look for another. Whether you enjoy isolation or prefer neighbors nearby is another consideration to ponder. And, of course, there is the matter of money: how much you can afford to put down, how much you can pay each month for a mortgage and taxes. Once you have made these decisions, pick an area or two to investigate. Get the catalogs of the Strout and United Farm real estate agencies, and look for ads in the Sunday paper real estate section. Also subscribe to local papers from the regions of your interest; these may provide lower priced listings plus information on land auctions.

When a property appeals to you, investigatefirst by phone and then in person. When looking, do not neglect small matters, such as television reception, the contours of the land, and the style of the farmhouse; but never lose sight of your ultimate goals or basic priorities, and gauge the property in that light.

To Buy or Not to Buy: Resist That Impulse

Once you have found a piece of property that appears to meet your needs, resist the temptation to come to terms. This is the time for an in-depth investigation rather than a purchase. After leaving the parcel, think about it, talk about it, try to remember its contours, and list all the things you do not like as well as the things you do. If after a week or so the land still is appealing, arrange to spend an entire day tramping about it.

Walk slowly about the property in the company of your family. Among the subjects of discussion should be these: Is the ratio of meadow to woodlot about what you have in mind? Does the woodlot consist of hard or soft woods? (The former are generally more valuable as timber and fuel.) Is the meadow overlain with ground cover, indicating some fertility? Is it swampy? Is there a usable residence on the property? If not, can you afford to build? Is there a road that cuts across the property into a neighbors driveway? If so, there is likely to be an easement on the parcel, conferring on the neighbor the right to cross at will. If there is no electricity, gas, or telephone service, ask yourself honestly how well you can get along without these conveniences. And if your goal is to be a part-time farmer and full-time resident, check into employment possibilities in the area.

If the answers to most of these questions are satisfactory, then begin a more formal survey of the property. For those who plan to grow vegetables, grains, or fruits, the question of soil fertility becomes a major factor in any ultimate decision. Take a spade and dig downway downin several widely scattered places. Ground that is adequate for good crops will have a layer of topsoil at least 10 inches deep; 12 or 15 inches deep is better. The topsoil should be dark, and when handled it should feel soft, loose, and crumbly to the touch. If the topsoil seems rich enough and deep enough, make doubly certain by taking several samples to the nearest county agent; he can analyze it for acidity (pH) and mineral content and tell you what crops are best to grow on it. Another way of discovering what crops the soil will support is to find out what the neighbors are growing. If the farm over the fence has a healthy stand of corn, and a thriving vegetable garden, the chances are good that the land you are looking at will also accommodate those crops.

When walking the land, look for evidence of soil erosion. Gullies are a sign of erosion, as are bared roots of trees and bushes. Parched, stony, light-colored soils indicate that erosion has carried off the rich topsoil. If you are only planning a small kitchen garden, erosion and lack of topsoil can be repaired. But if extensive cropping is your goal, the cost of restoring scores of acres to fertility may be beyond your reach.

Check the drainage capacity of the land. If the subsoil is so compacted or rocky that it cannot quickly absorb water, then the plants you sow are likely to drown. Also bear in mind that poor drainage can make it difficult to install a septic system, since sewage will tend to back up or rise to the surface. Inspect the property in the wake of a heavy rainstorm. If the surface is muddy or even very spongy, it is a sign that the drainage is poor. Dig several widely spaced holes in the ground, each one about 8 inches around and 3 to 4 feet deep. Check the soil near the bottoms. If it is hard-packed and unyielding to the touch, chances are it is relatively impermeable to water. Or pour a bucket of water on the ground, wait 10 minutes, and dig to see how far the water has penetrated. For the most accurate information, a percolation test by a soil engineer is necessary.

If you are planning on building a house, carefully inspect possible construction sites. The land for the house should be reasonably flat, with easy access to a public road. Do not overlook the sites relationship to the winter sun. A house with a northern exposure, particularly if it is on a slope, is likely to cost considerably more to heat than one with a southern exposure that can take advantage of the warming rays of the low-lying winter sun.

Finally, there is the all-important matter of waterthe lack of a reliable source of water for drinking and irrigation can make an otherwise desirable site worthless. The subject is discussed in detail below.

In all events, try to delay a commitment until you see the land in all seasons; both the blooms of spring and the snows of winter can hide a multitude of evils.

Buildings Are Important But Water Is Vital

In assessing country property the most important single consideration is the availability of an adequate supply of fresh, potable water. With water virtually anything is possible; without it virtually nothing. Consider, for example, that a single human being uses between 30 and 70 gallons per day; a horse between 6 and 12; a milk cow about 35; and a 500-square-foot kitchen garden, if it is to thrive, must have an average of 35 gallons of water per day. Even if the property is to be used only as a country retreat, a family of four will require a bare minimum of 100 gallons every day for such basic needs as drinking, washing, cooking, and sanitation. In short, complete information about water availability is an imperative when assessing country property. This is not to say, however, that a piece of land should, in all cases, be rejected if the existing water supply is inadequate, since in most instances a water system can be developed (see pp.4246). Nevertheless, this can be an expensive, laborious, and time-consuming effort, and it is far more satisfactory if a water system is already in place.

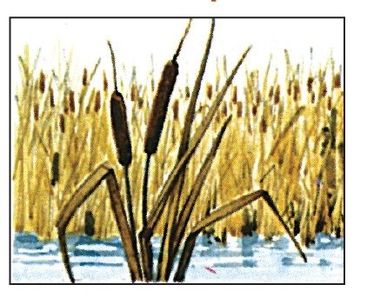

Plants that provide clues to water in dry country