Raising Ducks & Geese

Raising Ducks & Geese

John M. Vivian

Contents

Introduction

Before checking the latest advances in waterfowl raising for this small book, we looked into the prices youd have to pay in the supermarket for a duck or goose. The answer: $2.00 per pound for a little five-pound duck that would have to be stretched with plenty of wild rice, gravy, salad, bread, and a big mince pie to feed four people adequately. And a goose: $3.00 per pound for a young one in the ten- to twelve-pound range, if you can find one!

Now, prices have gone up across the board for food and all else, but this is ridiculous. For one thing, both kinds of birds will assay about a quarter fat. Its wonderful stuff for cooking eggs and popcorn, or greasing the hubs of old-time farm wagons or, boiled up so its good and clean, used to make soap or as is for hair pomade. Goose Grease is one fine, high-quality animal fat.

The reasons for these high prices are simple enough. Demand thus commercial capacity for either duck or goose products has just never developed very much in North America. Long Island duckling is a delicacy in many restaurants, and you can buy frozen ducklings in most large supermarkets (though my wife and I found that to dig out current prices we had to go mining deep in the frozen poultry bin to find a few ducks among the capons, leftover holiday turkeys, and such).

The store owner explained that there are only a few commercial meat duck operations in this country, and practically all geese are raised by small flock owners and are custom-slaughtered and dressed for Thanksgiving or Christmas. He did add that the popularity of each bird has picked up in recent years. Still, it will be a long time before commercial duck or goose will compare to the factory-raised chicken or turkey.

But store price is just one reason why you should raise your own. Probably the single most persuasive reason for raising ducks is that they will grow to five-pound (dressed) eating size in less than two months. By that time a chicken may weigh only half as much (depending on breed, feed, and management, of course).

As for geese, the only cost you really need incur is for your first birds and its considerable. They will cost you $8 to $10 per just-hatched gosling and considerably more per bird for mature breeding stock. If you want to try hatching fertile goose eggs, each egg will run you over a dollar. But after that, your costs can be practically nil, because geese are natural foragers, living on grass, weed seeds, and insects. In Europe, where the robust flavor of goose is vastly more popular than in North America, large flocks are herded from grazing field to field, traditionally by young children. But for the home place youll likely want no more than two or three pairs.

So lets start with the easier, smaller breed, the ducks.

Raising Ducks

The Kinds of Ducks

There are dozens of species of wild duck, divided mainly into two groups: freshwater or pond ducks and the saltwater varieties. No saltwater duck I know of has been domesticated.

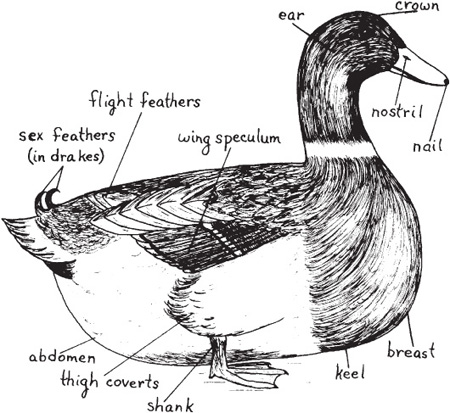

Practically all tame ducks have been bred from the wild Mallard. The male has green head feathers, a white ring around his throat, and variegated plumage in general. The female shares the patterns but not the bright coloration.

Mallards nest from the Arctic Circle to the middle latitudes all around the world. Winters are spent as far south as Borneo and just about anywhere else that the birds can find open water and plenty of food, which in the wild consists of pond weeds and such small aquatic creatures as snails and mosquito larvae.

The other wild ancestor of domestic duck stock is the Central American Pato, the Spanish word for duck. From this breed have been developed several color variants of Muscovy ducks accent on the Mus. (The name has nothing to do with Moscow, but is a slightly mauled pronunciation of Musk duck.) Muscovies look to be something of a cross between a duck and a goose, and they can get pretty large the male (or drake) often topping ten pounds, the lady (or duck) weighing some eight pounds.

Muscovies dont quack, but have a goose-like hiss. (Duck raisers tend to fall into two categories: those who like Muscovies, and those who dont.) The birds faces are bare of feathers and covered with red bumps called caruncles, the same sort of protuberances as a chickens or turkeys comb or wattles, but all over.

Muscovies are relatively slow growers, and unless they are kept tame they can be mean as all blazes. The flesh is perhaps the tastiest of all domestic ducks, if you enjoy the slightly wild, gamy flavor. However, unless you are into breeding your own and hatching the eggs, young ducklings of the species are too expensive to consider raising to eat. The last time I looked, a trio (drake and two ducks) of premium quality cost up to $75 or more, placing them (in our opinion) as fancy fowl, kept mainly for fun and show.

Among the Mallard-based breeds, by far the most common in commercial North American production is the White Pekin originally developed in Asia, as the name would lead you to believe. Both sexes are all white unless you feed them a lot of corn, in which case the plumage can yellow a bit but does no harm. A British-developed variation is the White Aylesbury.

Perhaps the fastest-growing duck, particularly if its water intake is restricted, the Pekin supplies those five-pound Long Island ducklings, which weigh about eight pounds live but come equipped with about three pounds of feet, feathers, and other discards. They reach green duck slaughter weight in less than two months from hatching.

Our favorite species is the Rouen (or domestic Mallard). Its mature weight is the same as the Pekin perhaps nine pounds for the drake, eight for the duck. The major advantage from our perspective is that the Rouens, developed in France, share more or less the same sex-differentiating coloration with their wild ancestors, though they are almost three times the size. The color lets you avoid the sex-identification process, necessary when its time to select young birds for slaughter or breeding.

The breeding flock usually consists of one male to each half dozen or so females. If you are new at bird sexing, you may end up as we did our first year (using the recommended Pekins) with an all-male breeding flock. No eggs.

Vaguely related to this is the story of the first time I tried caponizing (de-sexing males) of another kind of bird, chickens. This is major surgery, really, as the males testes are located in the abdominal cavity up along each side of the backbone. All went shakily but well till I came to one bird that had sexed out as a male but didnt seem to have the appropriate internal equipment. I removed the next-best-looking organs, figuring the bird to be a slow developer. The bird never did much of anything, and later, when we culled and slaughtered it, I discovered that he was a she Id removed the vestigial ovaries of a hen. Made a good stew, though. (Well get to sexing birds when we come to geese, where its more important, and the sexes particularly when young, eating size look identical).