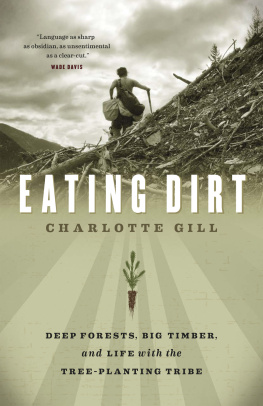

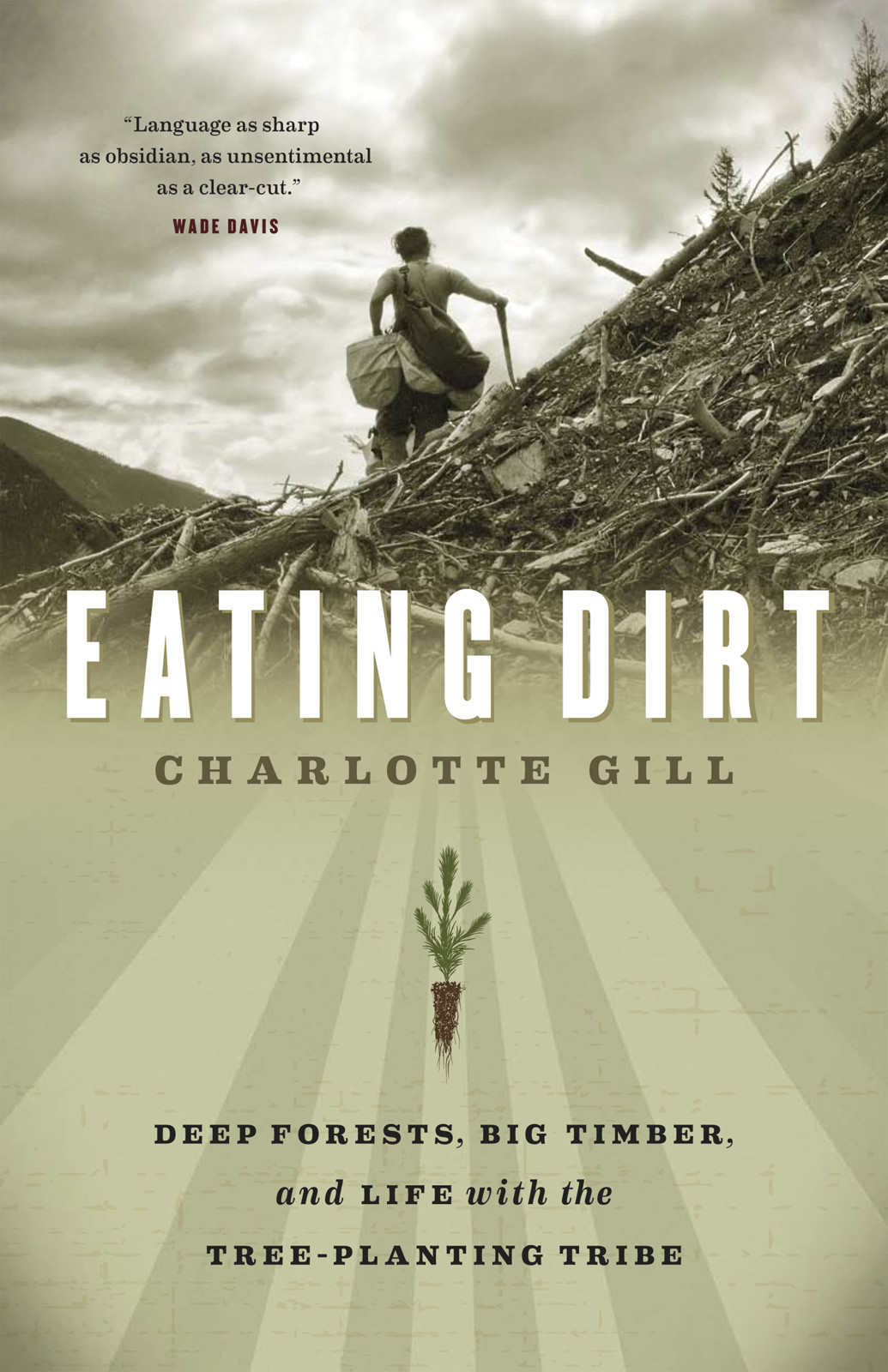

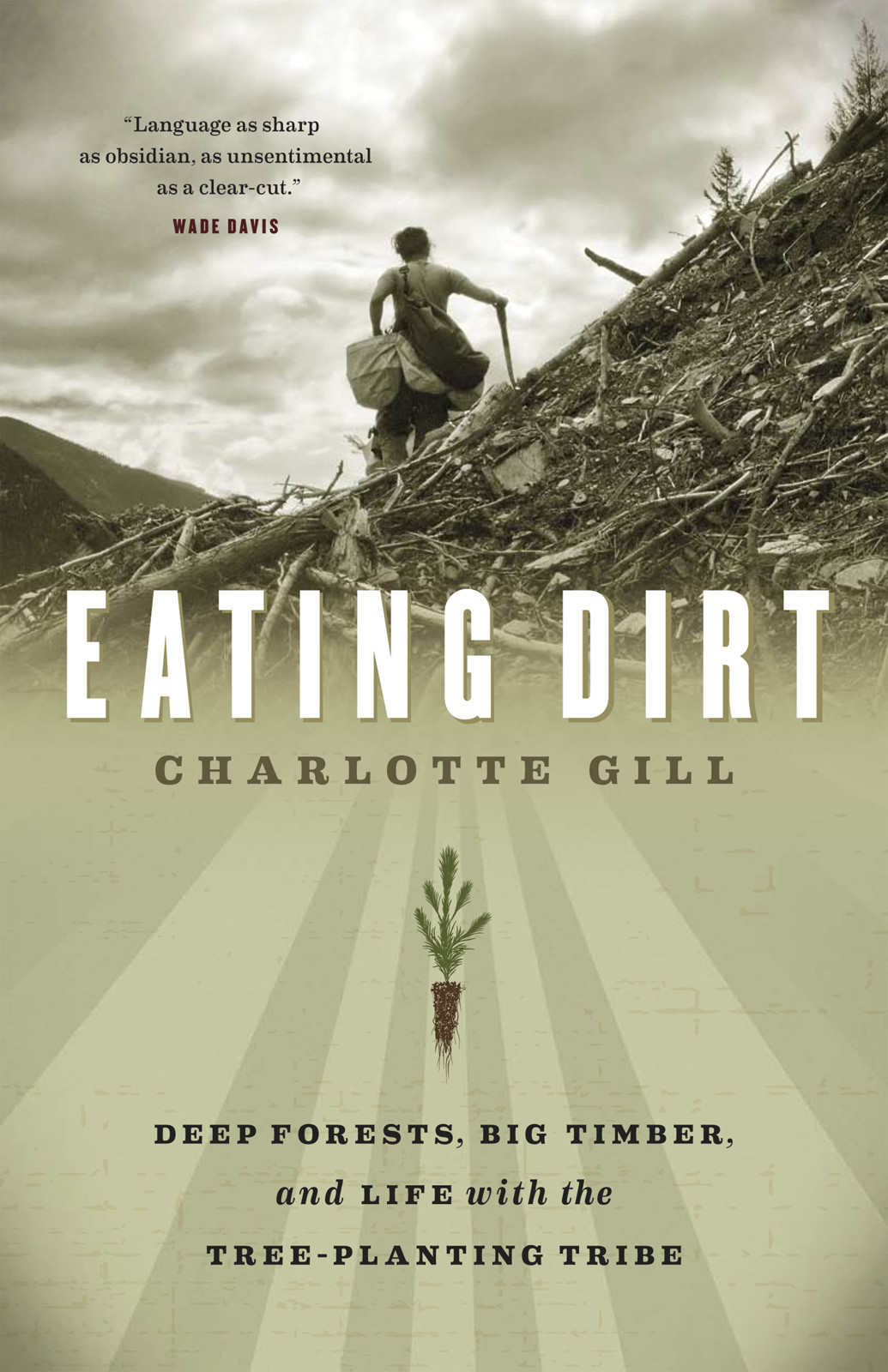

EATING DIRT

DEEP FORESTS, BIG TIMBER,

andLIFEwith the

TREE-PLANTING TRIBE

CHARLOTTE GILL

Copyright 2011 by Charlotte Gill

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior written consent of the publisher or a license from The Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright). For a copyright license, visit www.accesscopyright.ca or call toll free to 1-800-893-5777.

Greystone Books

An imprint of D&M Publishers Inc.

2323 Quebec Street, Suite 201

Vancouver BC Canada V5T 4S7

www.greystonebooks.com

David Suzuki Foundation

2192211 West 4th Avenue

Vancouver BC Canada V6K 4S2

Cataloguing data available from Library and Archives Canada

ISBN 978-1-55365-977-8 (cloth)

ISBN 978-1-55365-792-7 (pbk.)

ISBN 978-1-55365-793-4 (ebook)

Editing by Nancy Flight

Copyediting by Lara Kordic

Cover design by Naomi MacDougall

Cover photograph Hugh Stimson

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the Canada Council

for the Arts, the British Columbia Arts Council, the Province of British Columbia through the Book Publishing Tax Credit, and the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund for our publishing activities.

For the people of the tribe

I made a shift to go forward, till I came to a part of the field where the corn had been laid by the rain and wind. Here it was impossible for me to advance a step; for the stalks were so interwoven, that I could not creep through, and the beards of the fallen ears so strong and pointed, that they pierced through my clothes into my flesh. At the same time I heard the reapers not a hundred yards behind me.

JONATHAN SWIFT, Gullivers Travels, A Voyage to Brobdingnag

He was a work-beast. He had no mental life whatever; yet deep down in the crypts of his mind, unknown to him, were being weighed and sifted every hour of his toil, every movement of his hands, every twitch of his muscles, and preparations were making for a future course of action that would amaze him and all his little world.

JACK LONDON, The Apostate

Contents

{ }

W E FALL OUT of bed and into our rags, still crusted with the grime of yesterday. Were earth stained on our thighs and shoulders, and muddy bands circle our waists, like grunge rings on the sides of a bathtub. Permadirt, we call it. Disposable clothes, too dirty for the laundry.

The sun comes up with the strength of a dingy light bulb, dousing the landscape in shades of gray. The clouds are bruised and swollen. We stand in a gravel lot, a clearing hacked from the forest. Heavy logging machinery sits dormant all around, skidders and yarders like hulking metallic crabs. The weather sets in as it always does, as soon as we venture outdoors. Our raincoats are glossy with it. The air hisses. Already we feel the drips down the backs of our necks, the dribbles down the thighs of our pants. Were professional tree planters. Its February, and our wheels have barely begun to grind.

We stand around in huddles of three and four with toothpaste at the corners of our mouths, sleep still encrusted in our eyes. We stuff our hands down into our pockets and shrug our shoulders up around our ears. We wear polypropylene and fleece and old pants that flap apart at the seams. We sport the grown-out remains of our last haircuts and a rampant facial shagginess, since mostly we are men.

We crack dark, miserable jokes.

Oh, run me over. Go get the truck. Ill just lie down here in this puddle.

If I run over your legs, who will run over mine?

We shuffle from foot to foot, feeding on breakfast buns wrapped in aluminum foil. We drink coffee from old spaghetti sauce jars. We exhale steam. Around here you can hang a towel over a clothesline in November, and it will drip until April.

Adam and Brian are our sergeants. They are exactly the same height and wear matching utility vests made of red canvas. Heads bent together, they embroil themselves in what they call a meeting of the minds, turning topographical maps this way and that, testing the hand-held radios to ascertain which ones have run out of juice. Their lips barely move when they talk. Their shoulders collect the rain. We wait for their plan of attack as if it is an actual attack, a kind of green guerrilla warfare.

At the stroke of seven, we climb up into big Ford pickup trucks with mud-chewing tires and long radio antennae. We slide across the bench seats, shoving ourselves in together. Five diesel engines roar to life.

Adam sits at the wheel. He has an angular face, hair and skin turned tawny by the outdoor life, arresting eyes the color of mint mouthwash. He pulls out at the head of our small convoy. His pupils zip back and forth over the roads unpaved surface. He drives like a man on a suicide mission. No one complains. Speed is the jet fuel that runs our business.

While he drives, Adam wraps his lips around the unwashed lid of a commuter mug. He slides aluminum clipboards in and out of his bag and calls out our kilometers on the truck-to-truck radio. Logging trucks barrel down these roads, laden with bounty like land-borne supertankers. Adam slides his maps into various forms of plastic weatherproofing. Multitasking is his only speedas it is for all of ustoo fast, too much, and all at once. Were pieceworkers, here to make money, a lot of it, in a hurry. Earning our keep can feel like picking quarters off a sidewalk, and it can feel like an emergency.

Logging routes are like human arteries, main lines branching out into fine traceries. We pass from civilization to wilderness on a road with muddy ruts. Old snow decomposes along the shoulder. The land around here is jaggedly three-dimensional, fissured with gullies and brush-choked ravines. Mountains bulge from the seashore. We zoom through stands of tall Douglas-firs, conifers bearded with lichen. A green blaze, were driving so fast, skimming along the surface of our known world.

Most of us are veterans. Crusty, we call each other, like those Special Ops who crawl from war-ravaged mountains with wild hair, matted beards, and battle-mad glints in their eyes. Sean and Pierre were doing this job, they sometimes remind us, when the rest of us were in diapers. Pierre is fifty-five. He tells us he has a resting pulse rate lower than Lance Armstrongs. He tells us a hundred things, every day, in great detail. He shows us the display screen of his digital camera. He shows us photos of ravens and skunk cabbage. Snapshots from his civilian lifehis faraway kids, his foxy lady friends.

Sean is both wiry and muscular. He has a titanium hip. Some of his clothes are as old as his tree-planting careerthreadbare, unraveling around the edges. He plants trees for half the year and windsurfs the remaining portions. His lips and cheeks are speckled with liver spots from a life in the sun. But like Pierre, hes still going.

Jake, at twenty-one, is the youngest. Jake calls Pierre Old Man. He refers to himself as Elfie, in the third person.

Elfies not digging this action, he says. Elfie thinks this is fucked up.

Oakley and Jake are best pals. Jake is short and muscular, and he talks in rowdy shouts. Oakley is tall and sturdy. We always know where hes working, because his lunch box is a plastic tub that once contained a body-building supplement. Find the Mega Milk on the side of the road and you know Oakleys beavering away behind the rise. Oakley and Jake play Hacky Sack for hours every evening, and Pierre documents this, too, with his digicam.

Next page