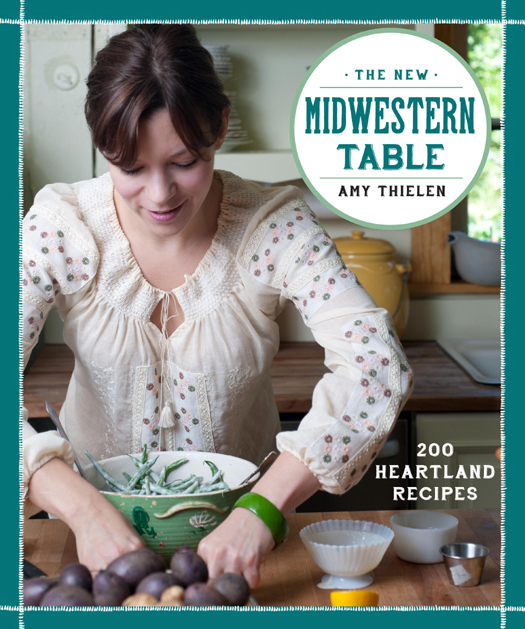

Copyright 2013 by Amy Thielen

All photography Jennifer May with the exception of , courtesy of Joan Dion

Illustrations copyright 2013 by Amber Fletschock

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Clarkson Potter/Publishers, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

www.crownpublishing.com

www.clarksonpotter.com

CLARKSON POTTER is a trademark and POTTER with colophon is a registered trademark of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Thielen, Amy.

The new Midwestern table/Amy Thielen.

pages cm

1. Cooking, AmericanMidwestern style. I. Title.

TX715.2.M53T49 2013

641.5977dc23 2012047058

Hardcover ISBN 978-0-307-95487-9

eBook ISBN 978-0-307-95488-6

Cover design by Marysarah Quinn

Cover photography by Jennifer May

v3.1

R eturning to this remote spot in the upper Midwest, to the forest at the edge of the plains, I realize that the immensity and flatness of this landscape are part of its charm, its severe weather a main character in the greater drama. The views are long, the winters cold, the summers hot, and the harvests are small, potent, and brief.

Nearly anywhere you want to go here involves a drive, so thats what we do, black triangular pines lining the road like a corrugated edge, guarding our passage. Driving past houses whose lights shine in the dark, the hanging fixtures glowing hearth-like over the kitchen tables, I wonder, as I have since early childhood, whats cooking inside those kitchens? What are the flavors that make their lives different from mine?

If Midwestern cooking has been hard to pin down, I think its because our best food has always been a celebration of this large, dynamic, plain-spoken place. Like the food, the vast interior of this country may seem ordinary to outsiders looking in, but it feels privately epic to those of us who live here. Film director Alexander Payne nails this sentiment when he writes that his home state, Nebraska, is at once the middle of nowhere and the center of the universe.

Even though the region is dotted with great restaurants, you cant judge Midwestern cuisine entirely on its public face; as is the case with other rural foodways, our most iconic dishes get passed hand-to-hand around a kitchen table. The roots of our cooking remain behind closed doors, where the old ways of preparing foodgardening, preserving, fishing, hunting, and otherwise plucking good things from the woods or the fieldsare not only still alive, but enjoying a transformative, active present tense.

Born and raised in the rural Midwest, I had an understanding of the regions food culture that deepened when, at age twenty-two, I moved with my boyfriend, Aaron, to his rustic nonelectric cabin on eighty acres near the unincorporated community of Two Inlets, twenty miles from my hometown in northern Minnesota.

A freshly minted English major, I cooked three days a week at a German-American diner on Park Rapids Main Street, working the early breakfast shift, which on Sunday mornings was the hellstorm of brunchschnitzels frying next to pancakes sitting next to spitting onions on the greasy griddleand on weekdays a pretty mellow business of feeding the regulars. With each ding of the bell I sent basted eggs, smoked pork chops, and hash browns to the boisterous group of coffee klatchers in the corner booth; a single order of white toast to the elderly twin sisters who sat side-by-side, chain-smoking; a lunchtime chef saladno eggs to my dad; and at 2:30 each afternoon, for Ron (a regular who seemed to be serving a parched life sentence), I put up three eggs poached hard and burnt rye, dry.

The rest of my time was spent at our house out in the woods, where the long distance from any power line dictated days spent performing the rituals of simple livingwood-hauling, water-pumping, vegetable gardening, berry-picking, and, of course, cooking.

After putting a kettle of water on my 1940s propane-fired Roper stove to boil for dishes, I would set up shop at the dining room table, an oil lamp burning patiently in front of me. The blush from the flame illuminated stacks of cookbooks, everything from ring-bound community collections to obscure classics. Obsessed with my new chores, I often called my grandma Dion for a refresher on making her famous white bread, to find out the desired temperature for fermenting my crock of sauerkraut, or how finely to grind the poppy seedswhich, by the way, is until theyre as fine as snuff.

Our neighbors, descendants of the areas original homesteading families, didnt hold back on advice or memories, either. Electricity was late to canvas this far-flung community, so still-good metal buckets were freely slung in our direction; spare parts for our grain mill were dug out from the backs of sheds; outhouse jokesoldies but goodieswere joyfully discharged on us. When we visited our friend Marie Kueber, she freely gave me her jelly recipe and my choice of the jeweled rows of jars setting up on her counter, but laughed heartily when I asked her to share her fruit-picking spot.

After three summers of nonelectric living (without power we couldnt stay past freeze-up), Aaron and I decided to move to New York City, instead of Minneapolis, for the winter. I signed up for culinary school and within nine months was working at David Bouleys Danube in Tribeca. Newly opened and recently given four stars from the New York Times , Danube was staffed with Austrian chefs (all veterans of three-star Michelin kitchens in Europe) and a strong brigade of New York City line cooks, and it was packed. I went straight from shelling garden peas on my porch to deveining foie gras. And back again, because I was still shelling peas, but now also blanching, peeling, splitting each one in half, and cooking them in truffle butter. I felt a weird kinship with these Austrians, who were frying noodles in browned butter and making pork sauce like my mom did. At Danube I saw how the European peasant food tradition has always influenced haute cuisine, and how simple rural dishessuch as those I grew up withcould be threaded into fine dining. One of the Austrian sous chefs drove it home, telling me that good cooking is potatoes and onions.