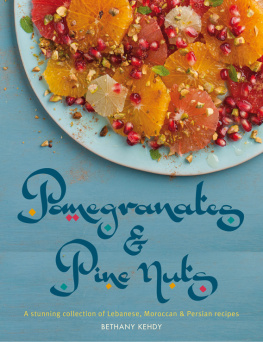

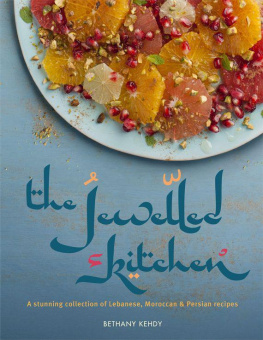

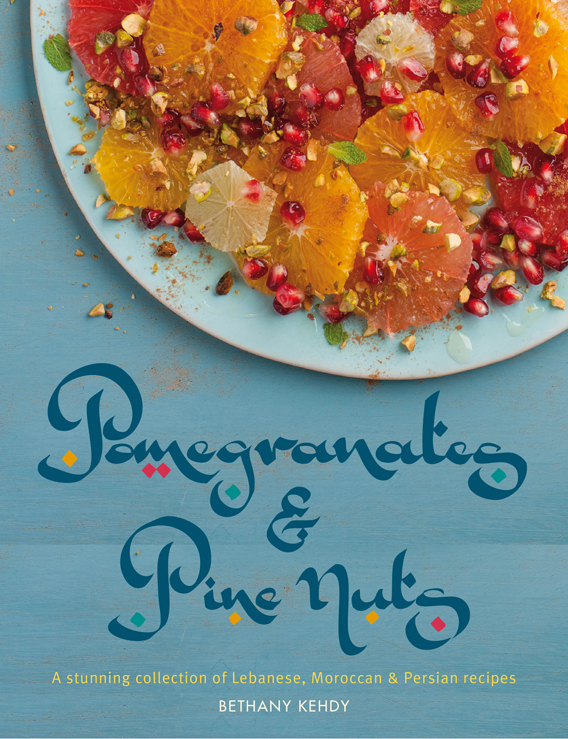

A stunning collection of Lebanese, Moroccan & Persian recipes

BETHANY KEHDY

DUNCAN BAIRD PUBLISHERS

LONDON

Culinary Reflections

B eirut, circa 1985. My delicate, fidgeting fingers in the bone-breaking grip of my grandfathers (jeddos) hand, his other hand firmly clasps the daunting, gold, lion-faced ornament mounted on his signature walking stick. As the foot of the stick beats against the asphalt, the thumping sounds are in sync with our steps. Together, we pace down a war-ravaged street in Fassouh, Ashrafieh, en route to my kindergarten. Along the way, we pause by the corner store, where we are greeted by the ruddy-cheeked owner, Rizkallah. Here, my jeddo spoils me with the sweets my young self adored so much. Most notable among them were Tutti Frutti and one we knew as Ras El Abed, with its fez-shaped crunchy outer fortification concealing a soft, meringue interior. As Rizkallah puts them on the counter, my jeddo gestures for me to choose from any one of the sugar-loaded pyramids populating the chilled cabinet. Jus ananas, jeddo, I proclaimpineapple juice, grandfather. He then pierces the inconspicuous aluminum-masked porta with the straw, before passing it to me.

The sweets are reserved for rcr, but only if I am a well-mannered girl, who has eaten all her tartine for lunch. This could be Arabic bread spread with labneh (strained yogurt) and dotted with olives, or perhaps cheese and cucumber, ham and cheese or cheese and jam, my grandmothers (tetas) favorite. Returning home with the sandwich uneaten isnt something I even dared to consider. Worse still would be to abandon it in the garbage, for somehow the school maitresse will discover this ultimate sin and bear news of it to my teta, much to Gods outrage. Allah atena akel ya tebreene, fee gheirna am b jouoGod has blessed us with food, others are starving.

These are my earliest memories of food, and the fear of my tetas wrath, which is a very plausible reason as to why my plate is never given a second to entertain a crumb.

The crumbs that led me to the kitchen

At home in Beirut, we could always expect a soul-stirring rendition from the seasons star characters as they rehearsed on the stovetop before asserting themselves center stage on our beige, checked, foldable kitchen table. Our meals consisted of many of the quintessentially Lebanese homecooked dishes, from the basic to the intricate. My tetas social foundation schedule, as active as olive oil in a Lebanese kitchen, meant certain days would be reserved for simpler dishes like mujadarah, musaqaa or mutabaqa. Mutabaqa, meaning layered in this instance, is a Lebanese relative of ratatouille, and was sometimes made too often for my jeddos palate. It often triggered the complaint, Tabate a albna ya maraYouve caved in our hearts with this dish woman. Playing on one of the several meanings derived from the root word tabaqa, it was a coy effort to express his underwhelmed appetite.

Regardless of what was on the table, though, as the clock struck noon, you could count on my grandfather to stroll over from his nearby law office every day of his married life. Lunch over, he would listen to the news on his radio, read a book or do some writing before his dreams hijacked him into a gentle afternoon siesta.

On Saturday mornings or during school vacations, I would shadow my teta as she went about her grocery shopping. First, we would whiz over to Hanna al laham (Hanna the butcher); both his body and his store still strong and upright, their facades evidence of times great pilgrimage. Ahlan b sit Adla,Welcome our lady Adla, he would greet her, a prelude to a short exchange of words about the well-being of each others families before the serious business of shopping began, signaled by Hannas request, Omoreen ya sitnaYour orders, Madame. In her stern voice, bereft of hesitation, teta would question the meats source and time of slaughter. Btarefn ya Hanna ma bebal gheir b ahsan shee.You know me, Hanna, I am only satisfied with the best.

At the greengrocer, she would shamelessly bury her hands right to the bottom of the vegetable pile, pulling out several contenders before picking the most worthy. In no way would she be outsmarted by the grocers conspiracy to keep the older vegetables most exposed. Tomatoes would get a full, twirling, close-up inspection as though they were a model at a casting. Eggplants would be fondled to test their tenderness, and often tossed back in disappointment. On bad mornings, I would hear her discontented muttering: Tetete, shou hal bdaa ya Rizkallah! Ndahle bas yejeek ahsan!Such terrible quality of produce! Give me a ring when you get better! she would announce, before turning on her heel and marching me out of the shop.

Cherished gifts from the land

I was four years old when my parents separated. Born in Houston, I returned to Lebanon with my father, while my siblings remained in the United States with my mother; it was a long time before we would all rendezvous again.

My mother was a beautiful, all-American Texan with golden blonde hair, shimmering, ocean-blue eyes and eyelashes that, when fluttered, could get her into Fort Knox. My Lebanese father was tall, robust and olive skinned, with large, piercing eyes. A hardworking, handsome, 20-something lawyer meant I spent most of my time soaking up the attention of my grandparents. My long, lean and imposing jeddo, with his chiseled cheekbones and a smile that, even in memory, can still light up my heart, was a renowned lawyer and author across the Arab world. His was a fascinating story of hard work, triumph and unmatched determination, deserving every blotch of ink on the flickering pages of Lebanons history books. His presence could shake a room, was something I often heard said about him. My grandmother, born to the only commercial tobacco farmer in Lebanon at the time, grew up along the shores of the northern town of Batroun. Stern and articulate, she never missed a beat, and it was said she could read a person and their motives in the glimpse of an eye. Family was the central focus of our life and I was always surrounded by the people who played a pivotal role in my upbringing: my grandparents, aunts and uncles.

My mother returned to Lebanon for a little while with my sisters in tow, and, as the civil war grew with fury and pain, we entrenched ourselves in our ancestral village of Baskinta, in the foothills of Mt. Sannine. My father set up a dairy farm where we spent the next five years embracing the land, its bounty, its unpredictable nature and the general, all-around, rugged goodness.

During the summers, my sisters and I would run in the terraces, hide in the pine forest, explore caves, swing from trees and compete to see who could jump the highest. Quite often, we were bribed to water the orchards, make cheese and help to bring in the harvest in exchange for an allowance that we squandered on junk food, usually a Snickers bar and a Pepsi. My idea of fun was to set up store just outside the house, my toy wagon overflowing with seasonal produce: corn, chickpeas, apples, anything I could sell to ghostly foot traffic. Needless to say, my only customer was my jeddo.