The Real McCaw

For Mum and Dad and my sister Jo.

Your love and support have helped me every step of the way.

And to all my other family and friends,

a very big thank you.

Contents

O ne of the first things Richie said to me when I saw him in late December 2011, a couple of months after the Rugby World Cup final, was I feel like Ive been in a tunnel for four years and just got out.

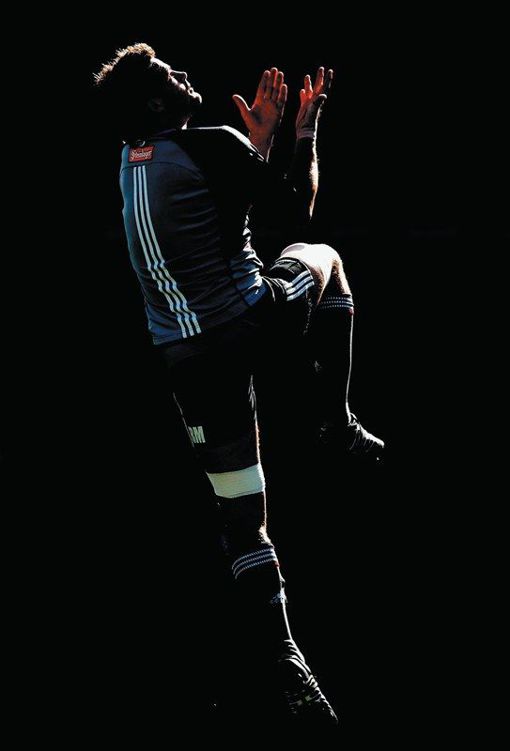

The image of him Id been carrying was from moments after the whistle blew in the final: that battered, bloodied warrior at the end of his tether, not so much on his last legs, but, as we now know, on his last leg, and looking a decade older than his 30 years.

Two months later, the young man who opened the door of his townhouse in Christchurch was scarcely recognisable as the same man, despite the moon boot. He looked radiant. He looked like a man with the sun on his face.

Id come down to Christchurch to ask a question, before anything was signed and sealed. I wanted to ask him face to face with no agents or publishers around if he was doing the book out of a sense of obligation or pressure, because if he was, I doubted that Id get the access or material the book would need. I should have known better. Richie doesnt commit to anything lightly, and after about two minutes, I knew it was a question Id never have to ask.

What was supposed to be a half-hour chat turned into an animated two-hour exchange about what we were going to do, how we were going to attack it. His opening statement suggested a way forward: that we go back into that four-year tunnel and discover what it took to find the light. From there, we would spin backwards at opportune times to defining events and people in Richies life.

As we did that, I came to see Richard Hugh McCaw as an increasingly rare alchemy of old-school and contemporary. His origins are as rural and tough as any All Black icons of the past, yet hes also a boarding school and university-educated urbanite. Hes technologically extremely adept, runs everything off his smart phone, but would as soon eat his own entrails as tweet. Hes the consummate professional yet essentially plays for the love of the game. Hes driven by an elemental fierce joy for the conflict, yet has sought out an understanding of the psychological underpinnings of behaviour and motivation. He trusts his instincts and what he knows, but is hungry to learn what he doesnt know. And perhaps the biggest paradox in his life these days: he now occupies a hugely public position in the nations psyche, yet is a man who likes to keep a substantial part of himself to himself.

He shares some characteristics it seems, with all champions. Dominic Lawson of The Independent was thinking of Roger Federerwho, more than most champions, gives an impression of languid grace and effortless geniuswhen he wrote: A proper investigation of the careers of the supreme achievers, whether in sport or other fields, reveals that they are based above all on monomaniacal diligence and concentration. Constant struggle, in other words. Seen in this light, we might define genius as talent multiplied by effort.

I would hesitate to call Richie monomaniacal, given his many other interests and pursuits, but my hope is that no one who reads this book should be left in any doubt about what it took for him to do what he did.

Greg McGee

July 2012

I was 12 years old when my father told me Id enjoy my rugby more if I got fitter. That was how he put it. I was a big kid, and he could have said I might make a better player for losing some weight, or that I might be selected for better teams. Instead, he said Id enjoy it more.

That stuck; I dont know why.

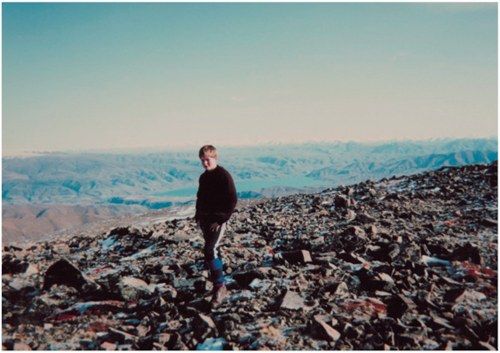

The County Council had left markers in blue paint on the verge of the loop road and I worked out these markers were 500 metres apart, so I tried to run five markers one way and back three or four times a week. Three kilometres, four kilometres, five. Right through late summer, as the sun burnt the valley brown, I jogged down our shingle driveway after school, past the sheep yards and on to the loop road.

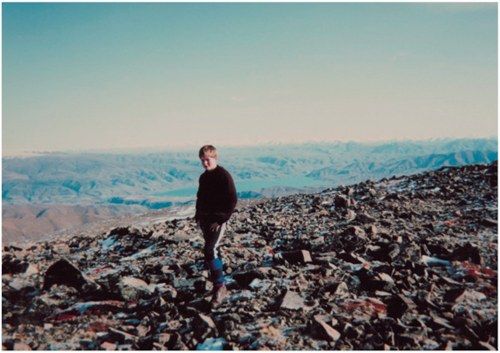

Id turn left and head up towards the Kirkliston Range, past my grandfathers farm, to where the road turned north and linked back to the main road running up the valley towards Cattle Creek. On either side, grazing and cropping flats rose to high-country tussock, where thered be snow on the tops through to October most years. Familiar sentinels watched over me: the Kirklistons in front of me, Mount Domett and Te Kohurau to the south, the Hunter Hills running up towards Mount Menzies to the north, where the road petered out and our river began. The Hakataramea River ran down through our valley and fed into the Waitaki. At the confluence, there was a one-way wooden bridge across to Kurow, a little two-pub town on the road that connected the Mackenzie Country basin to Oamaru on the east coast. These were the boundaries of the world I knew.

A year later, my world expanded when I became a boarder at Otago Boys High School in Dunedin. When they left me there, Mum and Dad told me this was a big opportunity that I had to make the most of. I put myself up for every sport that came along and worked so hard at my studies through the years that some of my mates from the First XV and First XI felt I was overdoing it, in danger of becoming a geek.

That didnt worry me. What worried me more was letting myself down.

Aged 12, on top of the Kirklistons. Behind me, Lake Aviemore looking towards Otematata.

In our end-of-year exams for sixth-form maths, I got 99.4 per cent. I missed one bloody mark. The very last question on the paper. I can still remember what I missed and how I missed itit was the only one I didnt check. There was a diagram of a circle, with a hexagon inside it. I had to work out how much of the circle was left if you removed the hexagon. I worked out the radius and tangents, made the calculations and wrote it down. I forgot to multiply it by six.

If I hadnt known the answer, I could accept that. I could forget it.

The reason I still remember every detail of it is because I did know it, but lost concentration.

The following year, my world enlarged again, when I was selected for the New Zealand Under 19 trials. We had one camp in Wellington before Christmas and one after, and wed been given a programme for the summer to get fit for the trials in late January.

After I got home from the first training camp, my Mums brother, John Bigsy McLay, and his family met us in Timaru for a family lunch prior to Christmas. Uncle Bigsy had been a really good rugby player whod been selected for the New Zealand Colts and New Zealand Universities. He hadnt quite reached his potential due to injuries from a car accident, but hed still played around 100 games for Mid Canterbury, many of them alongside Mums other brother, Peter. Uncle Bigsy was someone in the family who knew a bit about rugby and was a mentor, interested in strategy and motivation.

There were a few of us sitting around McDonalds waiting for our ordersmy folks, my sister Joanna, my aunty and cousins. I was sitting next to Uncle Bigsy and showed him the book Id been given, with the training programme in it.