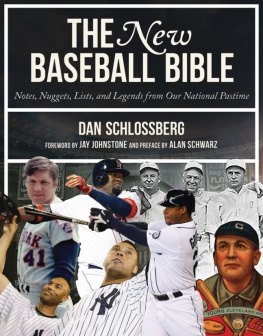

The Emerald Diamond

How the Irish Transformed Americas Greatest Pastime

Charley Rosen

www.harpercollins.com

To the Coyote Man, for his unwavering friendship

Cast your mind on other days

That we in coming days may be

Still the indomitable Irishry.

William Butler Yeats

You can take a boy out of Ireland but you cannot take Ireland out of the boy.

Irish saying

Contents

Baseball was mighty and exciting to me, but there is no blinking at the fact that at the time the game was thought, by solid sensible people, to be only one degree above grand larceny, arson, and mayhem.

Connie Mack (born Cornelius McGillicuddy)

F or the most part, the unfolding of an exhibition baseball game played in 1894 between the Pittsburgh Pirates and the Kansas City Cowboys would seem almost familiar to modern fans, full as the day was with men in uniform, albeit blousy wool ones, and with green grass, a blue sky, and scores of enthusiastic fans.

But then some profoundly unfamiliar playing rules would soon disconcert and confuse the modern onlooker. For example:

The entire game was played under the jurisdiction of only one umpire.

Balls bunted foul counted as strikes but not as third strikes.

The pitcher threw overhandedthat had been the case for only a few yearsbut both feet had to stay on the ground.

A hitter could take full swings and foul off a pitchers first twenty offerings and the count would remain 00, the only other exception being a foul tip gloved by the catcher, which would be a strikebut never strike three.

Pitchers were permitted to use any means to doctor the ballglomming it with mud, tobacco, licorice, or just plain saliva. These substances served to increase the sinking/curving action of the pitches, as well as to make the ball difficult for the hitters to track. Moreover, even when struck solidly, the heavy ball wouldnt travel very far.

Since the home team was required to provide only a handful of baseballs per game, they frequently opted to bat first in order to hit against relatively unblemished balls.

In the 1800s, the National League was the only universally accepted major league, but there were twenty-five other leagues in North America of varying professional status and stability. Even the NL was financially shaky, so before, after, and even during the season, most clubs sought to increase their revenue by engaging in numerous contests against whichever non-NL teams could offer them acceptable dates.

There were dozens and dozens of such extra games appended to every season.

Thats why the NLs Pirates were in Kansas Citys Exposition Park to play a midsummers contest against the Cowboys, one of the premier teams in the Western League. In fact, seventeen of the Cowboys were either once or future major leaguers.

Behind the plate for Pittsburgh was Connie Mack, a second-generation Irishman born to Michael McGillicuddy and Mary McKillop in Massachusetts. Mack was also the player-managerand would rightfully come to be celebrated as one of the eras most astute tacticians.

The Pirates led 86 and the Cowboys were batting in the top of the ninth with two outs and runners on second and third. Thats when the batter struck a fly ball that bounced just beyond the reach of Pittsburghs left fielder.

One runner scored easily, but the accurate relay to the shortstop and then to Mack was a cinch to beat the tying run to the plate by a large margin.

However, a feisty Irishman named Tim Donahue was the K.C. captain and third-base coach of the moment. As the runner rounded the bag, Donahue took off and ran ahead of him, much like a pulling guard leading a halfback into the line of scrimmage. Taking care to stay on the nether side of the foul line, Donahue plowed into Connie Mack just before the catcher could receive the throw.

Mack bounced one way, the ball bounced another way, and the runner was safe at home. Because Donahue never trod on fair territory, his trick was totally legal!

Since Connie Mack was famous for his own relentless search to discover exploitable loopholes in the existing rules, he was, however bruised, also quite impressed by Donahues maneuver.

In any event, the run counted and the score was knotted at 88 when the Pirates came to bat in the bottom of the ninth. Mack was coaching at third, with a man up and a man on first. The batter smacked a line drive over the third basemans head that was a sure double. What was uncertain, however, was whether the runner on first could come all the way around to score the winning run.

The odds seemed long when the Cowboys left fielder made a swift recovery and launched a strong throw toward catcher Fred Lake. Indeed, the ball was already in Lakes glove when Mack waved the runner homethen proceeded to barrel down the line in a duplication of Donahues successful ploy. Mack crashed into Lake with such force that the ball was, dj vu, knocked loose.

The umpire on duty signaled that the run counted and the game was over. In a flash, the riotous hometown fans stormed out of the stands and battled the police for control of the field, while Lake turned and punched the ump in the jaw.

Thereby concluding what was deemed to be just another exciting day in the ballpark.

No matter how violent, marginally legal, or downright illegal an action might be, winning a ball game always justified the means. And early in baseballs history, there was a name for this ruthless game plan.

Irish baseball.

H UMBLE B EGINNINGS

Arrival

Even if the hopes you started out with are dashed, hope has to be maintained.

Seamus Heaney

T he profound influence of the Irish people on virtually every aspect of Western culture is well known.

From James Joyce to F. Scott Fitzgerald; Maureen OHara to Daniel Day-Lewis. From Eugene ONeill to John OHara; Bruce Springsteen and Van Morrison to John Fogerty and U2. From Ed Sullivan to Stephen Colbert.

The list of American presidents with roots in the Emerald Isle is even more significant: Andrew Jackson, James Polk, James Buchanan, John Fitzgerald Kennedy, Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton, as well as both Bushes. (And as weve come to learn, Barack Obama is one-eighth Irish.)

But in America, the vital contributions of the Irish to what we call our national pastime remains largely unknown and absolutely unappreciated. Indeed, from the mid-nineteenth to the early twentieth centuries, it was primarily Irish baseball players who popularized and modernized the game.

B ack in the 1880s, two out of five players on what were considered to be major league teams were Irish.

Throughout baseballs glory years, names like Mickey Cochrane, Joe Cronin, and Joe McCarthy were legendary. Walter OMalleys was infamous.

That influence has continued into our lifetimes, with the likes of Dennis McLain, Al Kaline, and Mark McGwire. Paul ONeill is in New Yorks Irish-American Baseball Hall of Fame, and Kevin Millar told the Red Sox just to believe and they did. Tim McCarvers voice can still be heard on the air.

Even now, there are more than four dozen Irish players in the major leagues, the third largest minority group behind African Americans and Hispanics.

More impressively, Cooperstown includes a total of fifty-four players, managers, umpires, and executives of either full or partial Irish descent.

That represents the most numerous ethnic group of inductees.

T he Irish influence on our national pastime all began with an agricultural catastrophe that has been called the greatest human tragedy of the nineteenth century. At the time, it was believed to be a divine punishment inflicted on either sinful peasants or on greedy landlords and middlemen. Others opined that the disaster most likely had more rational causes: perhaps the static electricity and smoke created by the newfangled locomotives, or else deadly vapors leaking from underground volcanoes. In retrospect, it is generally agreed that the Irish Potato Famine was caused by a fungus that originated in Mexico before being transported in the holds of ships.