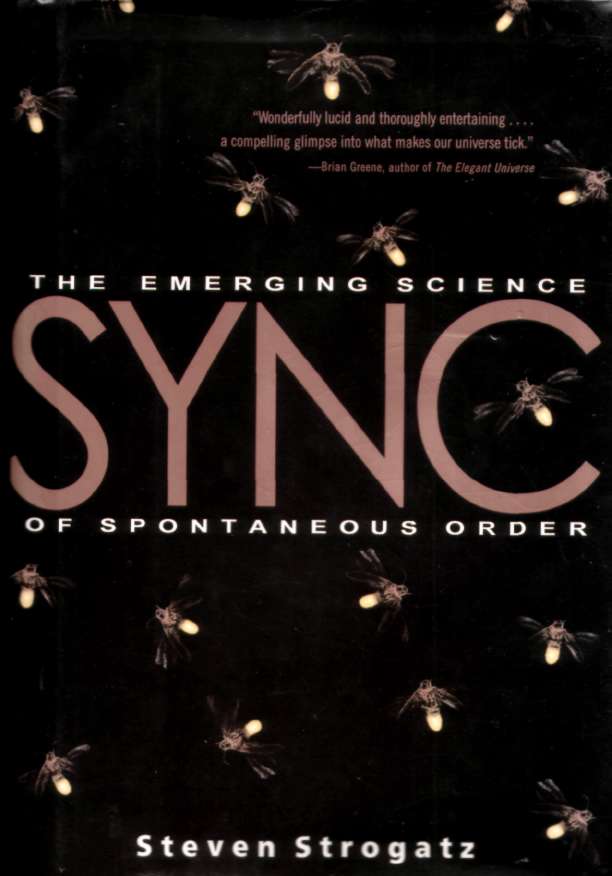

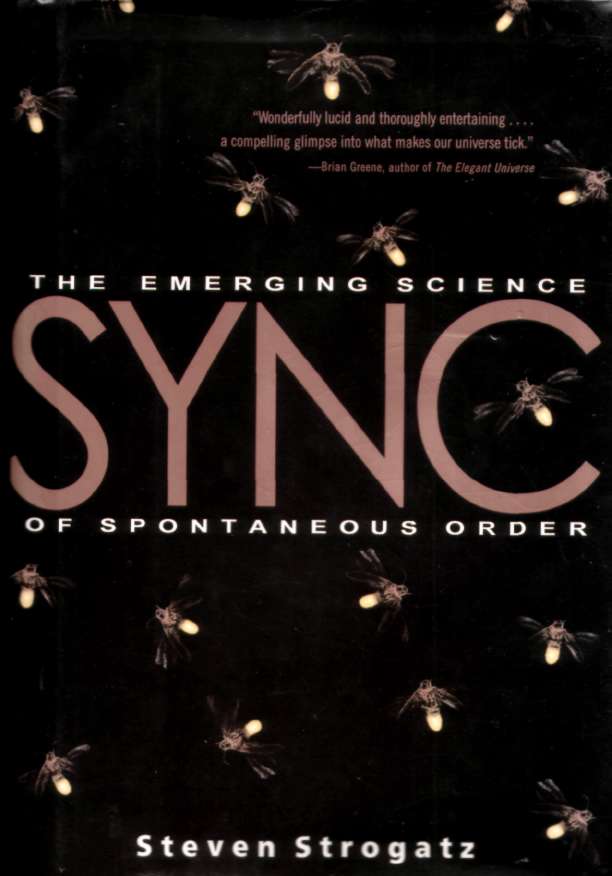

STEVEN STROGATZ

SYNC

The Emerging Science of Spontaneous Order

ISBN 0-7868-6844-9

FIRST EDITION

To Art Winfree Mentor, inspiration, friend

CONTENTS

Preface 1

I Living Sync

One

Fireflies and the Inevitability of Sync 11

Two

Brain Waves and the Conditions for Sync 40

Three

Sleep and the Daily Struggle for Sync 70

II Discovering Sync

Four

The Sympathetic Universe 103

Five

Quantum Choruses 127

Six

Bridges 153

III Exploring Sync

Seven

Synchronized Chaos 179

Eight

Sync in Three Dimensions 206

Nine

Small-World Networks 229

Ten

The Human Side of Sync 260

Epilogue 285

PREFACE

AT the heart of the universe is a steady, insistent beat: the sound of cycles in sync. It pervades nature at every scale from the nucleus to the cosmos. Every night along the tidal rivers of Malaysia, thousands of fireflies congregate in the mangroves and flash in unison, without any leader or cue from the environment. Trillions of electrons march in lockstep in a superconductor, enabling electricity to flow through it with zero resistance. In the solar system, gravitational synchrony can eject huge boulders out of the asteroid belt and toward Earth; the cataclysmic impact of one such meteor is thought to have killed the dinosaurs. Even our bodies are symphonies of rhythm, kept alive by the relentless, coordinated firing of thousands of pacemaker cells in our hearts. In every case, these feats of synchrony occur spontaneously, almost as if nature has an eerie yearning for order.

And that raises a profound mystery: Scientists have long been baffled by the existence of spontaneous order in the universe. The laws of thermodynamics seem to dictate the opposite, that nature should inexorably degenerate toward a state of greater disorder, greater entropy. Yet all around us we see magnificent structuresgalaxies, cells, ecosystems, human beingsthat have somehow managed to assemble themselves. This enigma bedevils all of science today.

Only in a few situations do we have a clear understanding of how order arises on its own. The first case to yield was a particular kind of order in physical space involving perfectly repetitive architectures. It's the kind of order that occurs whenever the temperature drops below the freezing point and trillions of water molecules spontaneously lock themselves into a rigid, symmetrical crystal of ice. Explaining order in time, however, has proved to be more problematic. Even the simplest possibility, where the same things happen at the same times, has turned out to be remarkably subtle. This is the order we call synchrony.

It may seem at first that there's little to explain. You can agree to meet a friend at a restaurant, and if both of you are punctual, your arrivals will be synchronized. An equally mundane kind of synchrony is triggered by a reaction to a common stimulus. Pigeons startled by a car backfiring will all take off at the same time, and their wings may even flap in sync for a while, but only because they reacted the same way to the same noise. They're not actually communicating about their flapping rhythm and don't maintain their synchrony after the first few seconds. Other kinds of transient sync can arise by chance. On a Sunday morning, the bells of two different churches may happen to ring at the same time for a while, and then drift apart. Or while sitting in your car, waiting to turn at a red light, you might notice that your blinker is flashing in perfect time with that of the car ahead of you, at least for a few beats. Such sync is pure coincidence, and hardly worth noting.

The impressive kind of sync is persistent. When two things keep happening simultaneously for an extended period of time, the synchrony is probably not an accident. Such persistent sync comes easily to us human beings, and, for some reason, it often gives us pleasure. We like to dance together, sing in a choir, play in a band. In its most refined form, persistent sync can be spectacular, as in the kickline of the Rockettes or the matched movements of synchronized swimmers. The feeling of artistry is heightened when the audience has no idea where the music is going next, or what the next dance move will be. We interpret persistent sync as a sign of intelligence, planning, and choreography.

So when sync occurs among unconscious entities like electrons or cells, it seems almost miraculous. It's surprising enough to see animals cooperating thousands of crickets chirping in unison on a summer night; the graceful undulating of schools of fishbut it's even more shocking to see mobs of mindless things falling into step by themselves. These phenomena are so incredible that some commentators have been led to deny their existence, attributing them to illusions, accidents, or perceptual errors. Other observers have soared into mysticism, attributing sync to supernatural forces in the cosmos.

Until just a few years ago, the study of synchrony was a splintered affair, with biologists, physicists, mathematicians, astronomers, engineers, and sociologists laboring in their separate fields, pursuing seemingly independent lines of inquiry. Yet little by little, a science of sync has begun coalescing out of insights from these and other disciplines. This new science centers on the study of "coupled oscillators." Groups of fireflies, planets, or pacemaker cells are all collections of oscillatorsentities that cycle automatically, that repeat themselves over and over again at more or less regular time intervals. Fireflies flash; planets orbit; pacemaker cells fire. Two or more oscillators are said to be coupled if some physical or chemical process allows them to influence one another. Fireflies communicate with light. Planets tug on one another with gravity. Heart cells pass electrical currents back and forth. As these examples suggest, nature uses every available channel to allow its oscillators to talk to one another. And the result of those conversations is often synchrony, in which all the oscillators begin to move as one.

Those of us working in this emerging field are asking such questions as: How exactly do coupled oscillators synchronize themselves, and under what conditions? When is sync impossible and when is it inevitable? What other modes of organization are to be expected when sync breaks down? And what are the practical implications of all that we're trying to learn?

I've been fascinated by such questions for 20 years, first as a graduate student at Harvard University and then as a professor of applied math at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Cornell University, where I now teach and do research on chaos and complexity theory. My interest in cycles goes back even further than that, to an epiphany I had as a freshman in high school. For one of the first experiments in Science I, Mr. diCurcio gave each of us a stopwatch and a little toy pendulum, a tricky gadget with an extensible arm that could be lengthened or shortened in discrete steps, like one of those old telescopes you see in pirate movies. Our assignment was to clock the pendulum's periodthe time it takes for one swing back and forthand to figure out how its period depends on its length: Does a longer pendulum swing faster, slower, or stay the same? To find out, we set our pendulums to the shortest length, timed its period, and plotted the result on a piece of graph paper. Then we repeated the experiment for progressively longer pendulums, always stretching the arm one click at a time. As I drew the fourth or fifth dot on the graph paper, it suddenly dawned on me that a pattern was emerging: The dots were falling on a parabolic curve. The same parabolas that I was learning about in Algebra II were secretly governing the motions of these pendulums. An enveloping sensation of wonder and fear came over me. In that moment of revelation, I became aware of a hidden but beautiful world that can be seen only through mathematics. It was a moment from which I have never really recovered.

Next page