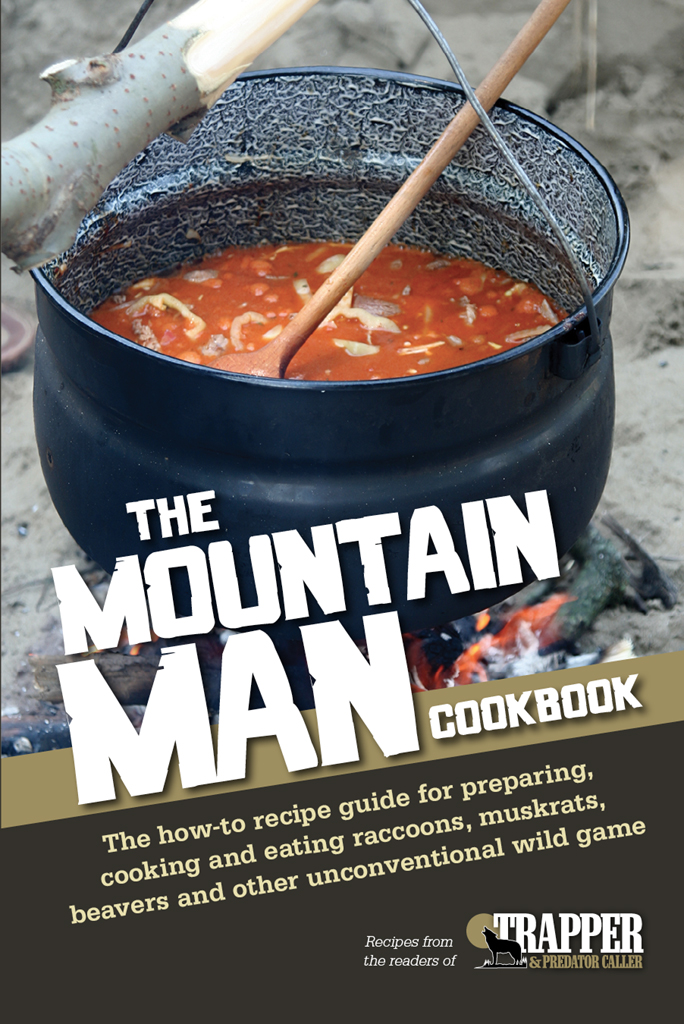

The how-to recipe guide for preparing, cooking and eating raccoons, muskrats, beavers and other unconventional wild game

Thank you for purchasing this Deer and Deer Hunting eBook.

Sign up for our newsletter and receive special offers, access to free content, and information on the latest new releases and must-have deer and deer hunting resources! Plus, receive a coupon code to use on your first purchase from ShopDeerHunting.com for signing up.

or visit us online to sign up at

http://deeranddeerhunting.com/ebook-promo

Introduction

Turning Furbearers into Food

By Serge Larivire

The people I work with in my day-to-day job have a different outlook on trapping than many of us do. Indeed, the James Bay Cree of northern Quebec is a First Nations group that still puts a high value on trapping but for reasons much different than our own. This group of aboriginal harvesters, a people that have survived for centuries in the inhospitable northern boreal forests, have learned long ago to use every source of energy available to them. For them, furbearers are simply food-bearers, and trapping for food is often just as important as trapping for fur.

Trapping for food? Yes, you heard me right. The animals we harvest for fur also provide high-quality meat for those who are willing to put a little time and effort into preparing them for the table.

And dont go thinking that eating furbearers is reserved only for those with native ancestry and those living a much more traditional lifestyle. Eating furbearers is probably one of the most underrated aspects of trapping. I am willing to bet that with time, more trappers will realize the value of the animals they catch not only in their fur sheds but also for their freezers.

After all, it has always been the belief of most of us that we should use as much of every animal we catch as possible. Yes, we catch furbearers primarily for fur, but when we can, we also collect and sell glands, and we can sometimes find markets for skulls, carcasses for bait and meat for the table.

In the true spirit of the earlier settlers, fully using the animals we catch includes using what we can for the table. Most First Nations groups would tell you that trappers are crazy to sell the pelt and throw the carcass of a beaver away, when for them beaver is considered the best bush food available. But before we get into the nitty gritty of recipes for furbearers, let us first examine which of the animals we catch are commonly table fare.

Fur and Food

The diversity of the furbearers we catch and sell for fur is amazing. Depending on where you live, the list of actual species we can eat varies from a handful of five or six to more than 20 species in some areas.

Just based on the number of species available, the vast majority of edible furbearers are from the family Carnivora carnivores, or meat eaters. These include all the canids (foxes, coyotes and wolves), mustelids (mink, marten, fishers and otters), felids (lynx and bobcats), procyonids (raccoons and ringtails) and ursids (bears).

But based on availability alone, the group that dominates trappers dinner plates often is Rodentia rodents. Of course, three species come to mind immediately beavers, muskrats and nutria. We could obviously add squirrels as well. Rodents are common fare worldwide, and the bigger the rodent, the more it is relished and sought as food. For a Northern trapper, beaver is like pork tender and juicy with a unique, mouth-watering taste.

But animals from other groups can also be consumed. I think first of the cats (lynx and bobcats), which also rank near the top for their quality of meat. Opossums (a marsupial) are also commonly consumed in some areas. Among the mustelids, the most often consumed species is the river otter. I have not met or heard of people choosing to eat mink. Interestingly, I have met some native people who remember eating skunks when available.

As for canids, or the dog family, they are probably the less commonly consumed furbearer group, at least by choice. They are consumed in some Asian countries, however. I mention the choice issue because it is obvious that in extreme cases, anything can probably be consumed if you are hungry enough. I have met elders who have eaten red foxes, marten and even mink, but that certainly is not a common occurrence today.

So, if you are willing to try to eat furbearers, the list of most-wanted includes beavers, muskrats, nutria, squirrels, lynx, bobcats, raccoons and bears.

I have tried all of the above, and all are top-quality meats that no one should be afraid to eat with a little care and some very basic, simple recipes. Those who know me know I am not a great chef, but I love to eat, love eating meat and do not mind trying new foods and recipes.

As a student, I remember one day years ago when I was sitting in a university cafeteria and a foreign student from France walked over as I was enjoying my lunch. When he peeked into my salad bowl and noticed some meat, he said Hi hunter, what are you eating today? I truthfully replied, Bobcat salad! To make your own, boil the back legs until the meat falls off the bones, let it cool, chop it up and mix it with whatever greens and dressing you like voil!

Basic Rules Before You Cook

This being said, just like any wild meat, there are some basic rules to follow to ensure a quality experience. The first one is freshness. The best animals to eat are those freshly caught, and eating a raccoon that has been dead in a trap and lying in the sun for days is a bad idea. Ditto for all species, so daily trap checks are best, although under-ice beavers will remain very good fare even if left in the cold water for a few days.

The second rule of thumb after you have a fresh catch is to process and cool the meat as rapidly as possible. I usually skin first and gut after because it makes the job of skinning easier. Either way, removing the skin and taking the guts out should not be delayed. I also pay special attention to keeping the meat clean on an animal I intend to eat. Avoid cutting glands on beavers because that will spoil the meat.

The third step is a simple examination for normality. I say this because you do not need to be a pathologist or an expert wildlife biologist to detect anything out of the ordinary. I look at the animal and only eat the ones that look healthy. As I gut the animal, I examine it further. If anything looks odd, I will throw it in the bait pile.

On rodents such as beavers, muskrats and nutria, the liver must be examined. Tularemia is a nasty disease that is detectable by strawberry livers livers with little white dots (dead cells) all over. If the liver looks unusual, throw it away. Dont take chances. Honestly, in all the years of cleaning and eating animals, I might have found only one or two with tularemia, so it is certainly not common.

If an animal looks healthy, is freshly caught and was rapidly gutted, cleaned and cooled, you can now consider the cooking part.

Cooking Furbearers

This is where your creativity and taste buds come into play. If you like fancy, you can let your imagination roam and enjoy furbearers in a wide variety of ways. The only thing I would urge is that you cook wild meat well regardless of species. Some animals, such as bears, might carry invisible parasites in the meat that can make you ill. Although this is rare, thorough cooking is the best way to avoid problems.