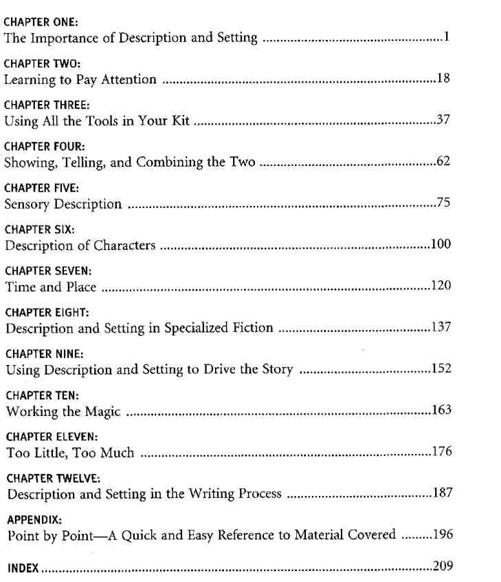

[ THE IMPORTANCE OF DESCRIPTION AND SETTING ]

One of the first things I learned about the difference between good and bad writing is that good writing is not entirely dependent upon the setting. And bad writing sometimes is.

I was in a college class called The American Novel on the third or fourth floor of the English building, watching the branches of a huge oak tree sway gently outside the open windows in the lazy breeze of a spring afternoon. We were nearly halfway through that odd duck of a decade called the seventies, and the professor used the adjective transcendental , which was almost always, in those times, paired with the noun meditation.

"Good writing is transcendental," the professor said. "It rises above time and place."

That little pearl has stuck with me ever since. And being for a long time now in the business of writinggood rather than bad, I hopeand teaching it, I can attest that it is true. If it weren't, then only people who grew up in rural Alabama in the early years of the Great Depression would be able to make much of To Kill a Mockingbird. But the fact is that any thoughtful reader can make a great deal of it, because To Kill a Mockingbird is not about Alabama or the Great Depression. Writing that is only about a time is not literature, it is history. If it is only about a place, it is geography. Literature is about neither; it is about people and all of the wide range of joys and troubles that people tumble into.

Now, having said that, I'd better quickly say this: Even though good writing is not entirely dependent upon the setting, a writer of fiction would be paving the way to miserable failure if he did not first create, using every tool at his disposal, the most clearly depicted time and place he could come up with. Because a story will not get very farmore specifically, your reader will not go very farwithout a setting that has been meticulously crafted.

Readers want to know a few things right up front, like what the weather is like and the lay of the land, the color of that lake, or the steep pitch of that steeple. Now whether or not these things have one iota to do with your story doesn't concern the reader. And it shouldn't; that's your business as the writer. That generic reader out there, who my students and I call the guy in Sheboygan, expects a few details from the start as part of his due for sitting down to spend any time with you at all.

The location and time frame of your story is more than just a stage for your characters to tromp around on. In some cases, the setting becomes a character itself. And all of the attendant detailssocietal conventions, seashores, mountains, regional dialectsdetermine the overall tone. In fact, if you do it right, setting and description become essential in your fiction. They become the foundation for the rest of your story to build on.

Very few existing novels or stories would work as well as they do, or work at all, in completely different times and places. It might be argued that To Kill a Mockingbird could be set in Nova Scotia in the 1980s, provided there was discrimination of some sort there, which there almost certainly was, discrimination being an abundant commodity in most times and places. In that venue, the story might possibly do the transcending my old professor spoke of. But, though it may survive such a transplant, it certainly wouldn't be the same book, or evenalmost surelya very good one. Harper Lee set her tale in the Deep South of the early 1930s, fertile ground for bigotry and family oddballs kept hidden away in crumbling old houses, a perfect bedrock for her unique novel.

Your fiction has to have a setting rich enough to match the story you intend to tell. It must be believable and sufficiently described to be as real for your readers as the rooms they are sitting in when reading it.

It's a tall order. But it's one that you'll have to fill before your writing can work on any level. This book will show you, through the use of explanations, examples, and practice drills, how you can go about establishing realistic, believable settings and providing engaging descriptions that will allow your readers to see, when they read your story, what you saw when you envisioned it.

craft and voice

Whenever I meet with a new class, the first thing I tell them is that creative writing consists of two things: craft and voice. I pilfer pretty liberally here from William Zinsser's On Writing Well, but he wouldn't mind; writers are usually gracious sharers and universally proficient pilferers. Then I tell the

class that I might be somewhat helpful to them regarding craft, which includes the tricks of the trade and various clever manipulation tools, like rabbits out of hats.

But when it comes to voice, the entirely individual way in which they spin their yarns, I admit that I'm not likely to be of any use whatsoever. They'll just have to dig around for that on their own. I can point them in the right direction, can show them examples of other peoples' voices, and can even tell them when they haven't found it. But finding it is a personal expedition.

This business of description and setting is rooted firmly in both craft and voice. The careful brush strokes that bring your story to life, the delicate tightrope walking between too little and too much, and the careful choice of a locale that makes your tale accessible to the guy in Sheboygan will require all of the tools in your kit and your ability to employ them. Jumbled in there-like screwdrivers and hammersare metaphors, similes, sentence-and paragraph-length variation, onomatopoeia, allusions, flashbacks, and many more things. Your job is to lift each one out as it is needed andin your distinctive voiceput it to work.

And while voice can't be taughtat least within the strictest definition of the word, by a teacher in a classroom or the pages of a how-to manual it can be learned. The process through which it finally emerges is a refiner's fire of mystical components, made up of honing the basic skills of storytelling, devoting plenty of time to reading a wide assortment of talented writers who have found their voices and put them to good use, and then undertaking, meticulously and slowly, the ancient enterprise of wordsmithing: the careful selection of each and every word and phrase.

the trinity

In each chapter, we'll look at various conventions and devices that undergird effective writing (craft), we'll dissect specific examples of how established writers have provided description and established setting (models), and we'll look at ways that you can go about the planning, writing, and fine tuning necessary to write quality fiction (wordsmithing).

Let's set some ground rules. Instead of dealing with craft and voice as two things, let's consider them from here on out as one. The tools and your unique use of them must be a single enterprise, the two fusing continuously into what will eventually be your finished product: a story or a novel. The

same is true of our dual topics, setting and description. One depends en tirely on the other, and separating them in our thinking or our treatment won't be helpful. For that reason, I've chosen not to break this book into two parts, one dealing specifically with setting and the other with description. They're going to have to work together in your fiction, so let's go at them as a single entity.

Finding and polishing the writing voice in which you will describe your setting is a solo voyage with you alone at the helm. But if you tinker sufficiently, using the many tools available to you, and pay attention to how other writers have used them, then your style will surface, like Ahab's white whale off there on the horizon. And it will get clearer and clearer as you row toward it. Here's a warning, however. This thing you are chasing is likely to give you as much trouble as the whale gave Ahab.