THE

DOG BOOK

Dogs of Historical Distinction

THE

DOG BOOK

Dogs of Historical Distinction

Kathleen Walker-Meikle

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Dogs have been mans closest companion for over 10,000 years, ever since they were first domesticated from the grey wolf. Since then, Canis lupus familiaris can be traced nearly all over the globe, in breeds from the burly Newfoundland to the diminutive Pekingese. Over the millennia, they have been keen hunters, trusted guardians or beloved pets; but some of the dogs featured in this book had more a unusual place in society, such as the multitude of performing dogs who delighted audiences on the stage and, later, on the screen. Wherever their owners went, dogs followed, and so we also find dogs in the middle of battlefields (occasionally getting lost!), in witchcraft trials, mascots for regiments and postal workers, and even flying over the North Pole

Throughout history, the most praised quality of the dog and that which set it apart from other animals has been its loyalty and devotion to its master or mistress. Although this is an anthropomorphic interpretation of canine behaviour, it forms the basis of many of the tales found in this book, such as those animals pining on their masters grave, or trying to save them from danger. Basic rituals of dog-ownership such as keeping the animal fed, or adorning it with specialist accessories such as collars and leashes are also in evidence across the ages, along with the related perils of overfeeding your pet or extravagantly spending a fortune on coats (or in the case of one Indian prince, an elaborate canine wedding complete with elephants in attendance!).

This book can only recount a fraction of famous accounts of historical dogs, but presents a selection of memorable movie-stars, pampered palace pets, performing poodles and dogs on the battlefield through various mediums including satirical poems and anxious newspaper notices for stolen animals. There are loyal dogs and spoiled pets, tales of exemplary behaviour and misbehaviour, and the beloved companions of famous figures including Prince Rupert of the Rhine, Lord Byron and President Roosevelt. In literature they have been alternately praised and satirised, due to the vast affection their owners have long lavished upon them. From Roman mosaics to the Bayeux Tapestry and depictions of the Last Supper, the iconography of dogs can also be found almost everywhere, and touching personal portraits of owners and their dogs reveal how a pet often became an essential and proud part of their identity. Keep an eye on history, and you will start seeing dogs everywhere!

Kathleen Walker-Meikle

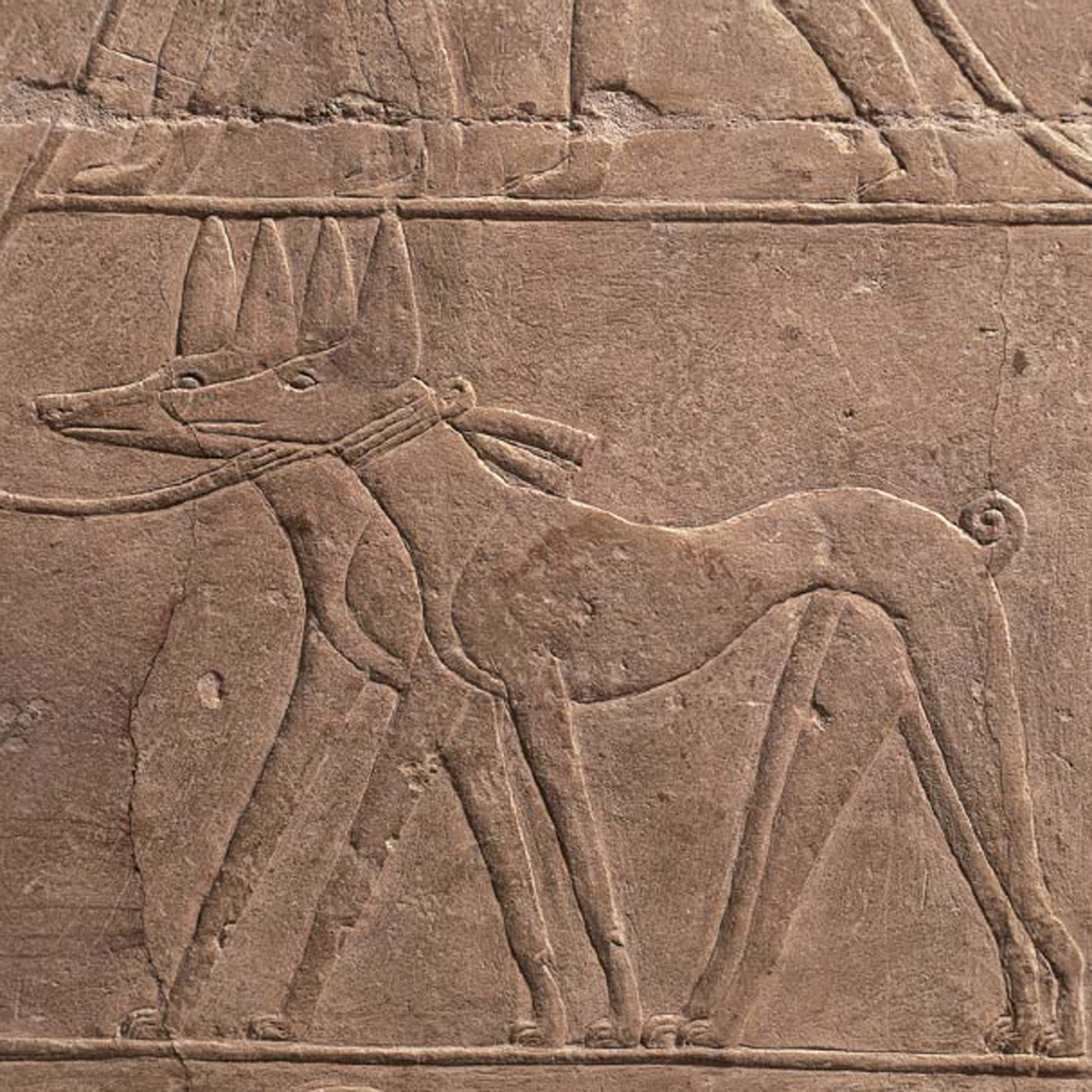

An inscribed limestone tablet discovered at Giza in 1935 attests the elaborate burial of Abuwtiyuw, most likely an Ancient Egyptian sighthound , which belonged to an unknown pharaoh of the Sixth Dynasty (23452181 BC). Only the tablet survives, but it is likely that the dog was mummified, judging from the gift of linen. It reads:

The dog which was the guard of His Majesty, Abuwtiyuw is his name. His Majesty ordered that he be buried [ceremonially], that he be given a coffin from the royal treasury, fine linen in great quantity, [and] incense. His Majesty [also] gave perfumed ointment, and [ordered] that a tomb be built for him by the gangs of masons. His Majesty did this for him in order that he [the dog] might be Honoured [before the great god, Anubis]

Dog mummies have been discovered in many Egyptian sites; the largest collection of ancient canine graves is the burial ground of several hundred unearthed at Ashkelon (in modern day Israel). The dogs were buried there over eight decades in the second half of the fifth century BC. They were all sighthounds (resembling modern greyhounds or whippets), the most documented of Egyptian dog breeds.

Relief of a scene at Necropolis, featuring two Ancient Egyptian sighthounds (c.2349 BC).

This detail from a seventeenth-century tapestry shows Argos recognising his master Ulysses.

Homers Odyssey, written around 800 BC, recounts the legendary Greek hero Odysseuss long adventures to return home to his kingdom of Ithaca after the end of the Trojan War.

Odysseus faithful dog Argos had been a young puppy when his master left for war, and is the only one on Ithaca to recognise him when he returns after twenty years. Neglected and covered in fleas, Argos lay on a dung heap by the stables, but pricked up his ears at his masters approach, wagging his tail. Odysseus saw Argos but could not greet him, due to being in disguise instead he shed a hidden tear for the loyal hound. He asked his companion, the swineherd Eumaus, about the dog. He explained that the dog belonged to someone who had died in a far country and had been a magnificent hunting hound but had now fallen on evil times, for his master was gone and the women no longer took care of him. Odysseus entered the hall of the palace and faithful Argos passed into the darkness of death after seeing his master once more.

Glazed ceramic amulet representing Anubis, the guardian of the tombs. Dated 400030 BC.

The Egyptian god Anubis oversaw the mummification process. By weighing the heart of the deceased against the feather of truth, he decided whether they should enter the otherworld or be eaten by the Devourer (part lion, hippopotamus and crocodile).

Anubis is his name in Greek his Egyptian names are Anpu, Inpw and Yinupu. He had many epithets, such as He Who is in the Mummy-Wrappings and Chief of the Necropolis. He is depicted as half-human jackal, although there is confusion concerning exactly which canid he was supposed to be a jackal, a wolf or even a wild dog. Recent DNA studies have proved that the Egyptian jackal is actually a subspecies of the grey wolf.

In Egypt, his cult centred in a town the Greeks called Cynopolis, meaning the City of the Dogs. The Greek writer Plutarch (c. AD 46120) wrote that a small civil war erupted when a resident of Cynopolis ate an Oxyrhynchos fish. The people of Oxyrhynchos began to attack dogs, which resulted in communal violence. The cult of Anubis was still extant in the second century AD.