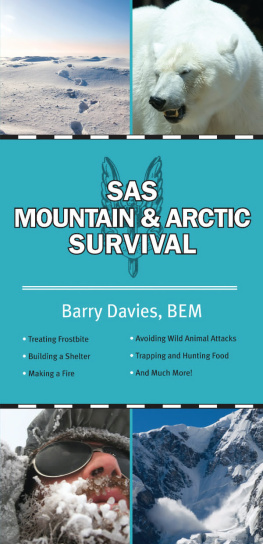

SAS

MOUNTAIN

AND ARCTIC

SURVIVAL

SAS

MOUNTAIN

AND ARCTIC

SURVIVAL

Barry Davies, BEM

Copyright 2012 by Barry Davis

All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

ISBN: 978-1-62087-206-2

Printed in China

Contents

Introduction

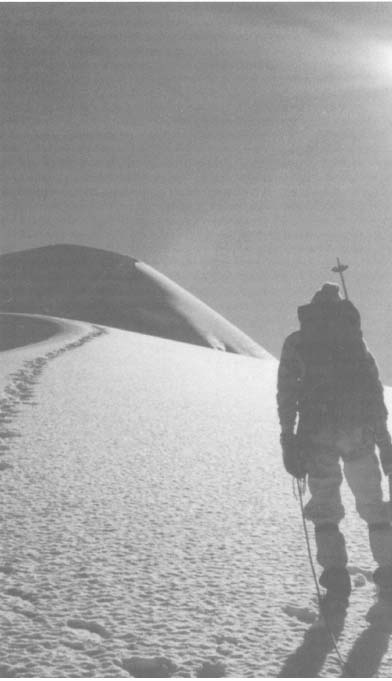

As with any hostile environment, mountain and Arctic regions can be dangerous, but the same basic rules of survival apply no matter where you find yourself: blend and integrate with the elements, and resist the urge to fight them.

It is difficult to imagine that anyone would deliberately go unprepared into a mountain or Arctic region. The most serious situations arise when an aircraft crash-lands or some other form of transport breaks down during a deep penetration into the wilderness. In all cases, providing you are uninjured, your chances of survival are good. In both winter and summer the northern Arctic offers an abundant supply of water and food; shelter can be found in the tree line, or created even on the barren ice floes. Provided that you successfully protect yourself against the risk of freezing to death your chances of survival and rescue are good.

Even in the worst cases, when you have been plunged into a survival situation by a plane crash, you should still be able to salvage enough equipment to survive for several months. In wartime, prisoners who have weighed up their chances realistically prior to any escape from, e.g., an Arctic prison camp and who have prepared themselves and their equipment intelligently have found that the Arctic offers survival conditions that most of us can deal with.

Latitudes higher than 66 degrees 33 minutes North define the area known as the Arctic Circle. It covers some 21 million square kilo-metres (approximately 8 million square miles), of which two-thirds are occupied by the Arctic Ocean. More than half of the ocean is permanently covered with layers of pack ice.

In winter the Arctic temperature can drop as low as -65C. Winters in the Arctic are long and severe, with the ground frozen much of the time. Summer lasts for around four months during which the ground thaws sufficiently to allow moisture to reach the roots of the trees and plants. The northern landmass changes as you move south, from pack ice to a rich grassy vegetation (the tundra), and on into a wide forest strip; in parts this is up to 1500km (900 miles) deep from North to South. Man and beast have occupied this inhospitable area throughout the history of mankind; depending upon the time of year, it is rich in plant life, fish and wild animals.

By comparison the Antarctic continent surrounding the South Pole is a forbidding land almost devoid of plant and animal life. Scientists have found a variety of lichens and insect life, but insufficient to sustain life for survival purposes. The landmass Is greater than that of Europe, and is entirely covered by a dense sheet of ice which averages over 2000m (7,000ft) thick. The Antarctic is much colder than the northern Arctic, with temperatures falling as low as -89C (-128F). Animal life is mainly restricted to birds, seals and penguins, the latter spending most of their life in the water. Winds in the Antarctic can reach speeds of up to 160kmh (1OOmph), driving snow 30m (100ft) into the air. It is imperative that any survivor takes shelter from such a snow blizzard; apart from the lack of visibility, the wind forces down the air temperature, creating deadly hypothermic conditions. Short-term survival is possible, but would depend upon making early contact with one of the many scientific research stations which are dotted around the outer edge of the Antarctic.

Similar conditions prevail in high mountain areas where, especially during winter months, the harsh environment, changing weather and snow conditions can pose a serious threat to survival. With the right skills and equipment, however, your chances are good.

Arctic Clothing &

Equipment

To venture into the Arctic without the proper clothing and equipment is to invite disaster. Man is a tropical animal whose body functions best between 96F and 102F; above or below that relatively narrow range the health may start to decline.

The maintenance of body temperature will help prevent cold injury. The main factors to protect against in the Arctic are low temperatures, wind, and ground conduction. Modern clothing materials such as Gore-Tex make ideal outer protective shells, but the inner layers are equally important. Safeguarding heat loss from your head, hands and feet will play a major part in any Arctic survival, and again the layering principle can be employed.

How the Layer System Works

Body heat is produced by activity; the more strenuous that activity the more heat is generated. By using the layer system we can control this heat. For example, blankets on our bed trap our body heat and provide warmth while we sleep; too few blankets and we get cold, too many and we overheat. The same principles apply every time we dress ourselves. However, in the Arctic we will need several layers of the right fabrics to control our body temperature. Removing a layer reduces trapped heat, adding a layer increases it. By doing this we also control sweating, and the damping of clothing next to the skin. The layer system applies to the whole body, overlapping where need be. The inner layers are used to provide insulation while the outer layers provide ventilation.

Clothing next to the skin should be made of a thin, cotton material, loose-fitting and able to absorb perspiration. This layer must be kept clean.

The second layer should ideally be made of tightly woven wool with adjustable fastenings at the wrist and neck.

A third layer should consist of a fleece-lined shirt or jacket with a hood. This layer should be easily removable.

The final outer layer needs to be both waterproof and wind-proof, with a large hood. For Arctic temperatures this garment should be filled with a padded insulating material similar to that used in sleeping bags.

Protecting the Head The head accounts for around 47% of heat loss, and its protection is vitally important.

An insulated hat with pull-down earflaps will stop much of your bodys heat loss, but make sure it does not fit too tightly. The military use a 30cm (12in) long woollen tube which they call a head-over. This is used under the hood of any outer garment; it slips over the head forming a seal at the neckline. In extreme cold conditions when it is necessary to remove the outer hood, the head-over can be pulled up to protect the ears and head.

Next page