ALSO BY NIGELLA LAWSON

HOW TO EAT

The Pleasures and Principles of Good Food

HOW TO BE A DOMESTIC GODDESS

Baking and the Art of Comfort Cooking

NIGELLA BITES

From Family Meals to Elegant

DinnersEasy, Delectable

Recipes for Any Occasion

FEAST

Food to Celebrate Life

NIGELLA EXPRESS

130 Recipes for Good Food, Fast

NIGELLA CHRISTMAS

Food Family Friends Festivities

NIGELLA KITCHEN

Recipes from the Heart of the Home

NIGELLA FRESH

Delicious Flavors on Your Plate All Year Round

Copyright 2012 by Nigella Lawson, Pabulum Productions Limited.

Photographs copyright 2012 by Petrina Tinslay.

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Clarkson Potter/Publishers, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

www.crownpublishing.com

www.clarksonpotter.com

CLARKSON POTTER is a trademark and POTTER with colophon is a registered trademark of Random House, Inc.

Originally published in Great Britain by Chatto & Windus, an imprint of the Random House Group Limited, London, in 2012.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available upon request

eBook ISBN: 9780770437022

Hardcover ISBN: 9780770437015

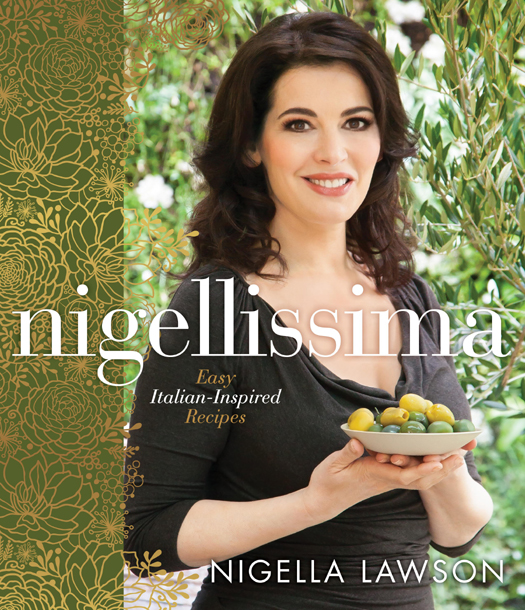

Jacket design by Ashley Tucker

Jacket photography by Petrina Tinslay

v3.1

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

IT WAS WHEN I WAS SIXTEEN or seventeen that I decided to be Italian. Not that it was a conscious decision; nor was it even part of the teenage armory of pretensionthe battered Penguin Modern Classic stuffed conspicuously into a basket, the Anello & Davide tap shoes, the cult of the Rotring pen filled with dark brown inkof the time. No: I simply felt drawn to it, to Italy. While doing other A-Levels (the British equivalent of high school examinations) I did a crash course in Italian and, before I knew it, Id applied to read Italian at university. I did an entrance test in French and Germanin the olden days you still sometimes had to do thiswith a plea to swap French for Italian. Certain universities then, and I would guess still now, took a slightly condescending view toward the Romance languages: at Oxford, the authorities saw no reason why Spanish, Italian, or Portuguese couldnt be studied at degree level from scratch; if you knew Latin and French, they blithely assumed you were pretty well there, anyway.

At my interview, I talked of spending my gap year in Italy, and it came to pass that I did. I think I may have implied that my destination was along the lines of a stint at the British Council in Florence. And Florence was, indeed, where I wentat firstnot as a student of culture, but as a chambermaid. Id sworn to do anything to earn a living except clean restrooms, so of course thats what I ended up doing. But I did learn Italianafter a fashion. A year or so on, in a translation class at universitywe had been given the task of rendering, orally, a piece of the History of Western Philosophy , or some suchmy tutor said to me, Thats fine grammatically, Nigella, but Im sure Bertrand Russell wouldnt have sounded like a Florentine greengrocer!

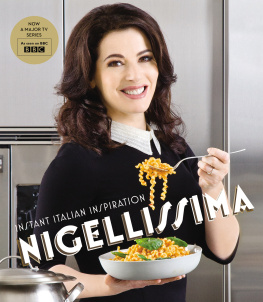

I wish I sounded like a Florentine greengrocer now; I am afraid my Italian these days has the halted stammer of any smitten British tourist. But if I dont spend as much time in Italy as Id like, I bring as much of Italy as I can into my kitchen. And that is what this book is about.

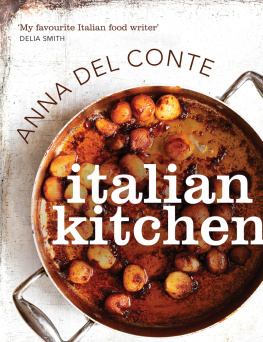

I fear I never write the introduction to a book without claiming that I had the germ of an idea for it way, way back. Its how I work, though: the books I really want to write are the ones I put off for longest. I will be charitable to myself here, and claim that it must be because I need to let them filter through and become part of me first. It is true that the book I have now written is not quite the one I originally intended. Thats how it should be if the process of writing has any meaning. I had thought that one day I would write my Italian book and that it would concentrate on food as it is cooked in Italy. As someone who, since putting the project on the back burner, has bought a whole wall full of Italian cookbooks (about five hundred titles at the most recent count), I no longer felt so driven to write it. I also had a sense of embarrassment about my original idea; without the fearlessness (or arrogance) of youth, I blushed at the presumption of an English persons finger-wagging on the subject of authentic Italyfor all that I derive much pleasure as well as instruction from many Anglophone Italian cookbooks. And yet still I felt that Italian food was so central to me, and to how I cook, that I couldnt drop the project altogether.

In that family-run pensione in Florence where I worked as a chambermaid, I spent a lot of time with Nonna the paternal grandmother, straight from Central Castingin the kitchen. She didnt teach me to cook, but I learned from her. Actually, I cooked already but, being a child of the time in general, and of my Francophile parents in particular, my way in the kitchen was profoundly influenced by France and its cuisine. In that tiny little kitchen in Florence, I learned about pasta and how the sauce that dresses it must not swamp; I learned to cook meat on the stove top, and to make the simplest, scantest gravies with deglazed pan juices; I learned about verdura , cooked soft and served at room temperature, so unlike the crunchy vegetables that were strictly comme il faut in France-fetishizing Britain at the time. I learned a lot more besides. I had very little money (chambermaiding is hardly lucrative, and a schoolfriend and I were sharing the position and hence also the accommodation and the wages) so eating out was limited. I mean, we did eat out a lot, but that mostly involved stretching a carafe of wine, a basket of that unsalted Tuscan bread, and a bowl of tortellini in brodo over an entire evening; luckily, when youre nineteen and female in Italy, you can pretty well get away with anything. When we ate in the evenings in our room with a view (squished together on a window ledge overlooking the Duomo) we could just afford between us a bottle of wine, a loaf of bread, 2 pounds of tomatoes, and some olive oil. And when our wages didnt stretch to wine, we drank the vodka and gin wed bought duty-free on the way over, spritzed with dissolvable aspirin from our medicine bag; mixers, costing more than wine, were beyond our budget.

So, of course, it made sense to be in the kitchen, eating with Nonna. This was strictly prohibited by her son, but he and his wifeUgo and Gabriellawere often at their farm in the country, and her grandson, Leonardo, was at school, so Nonna would invite me in for company, unaware that she was teaching me how to cook. She taught by example and involvement, the only way any of us really learn anything important. Thus, she drew me in, and from then on, I never wanted to be anywhere else.

But the recipes that follow are not those that issued from Nonnas kitchen: they are what I cook and, more important, how I cook, in mine. Ive often joked that I pretend to myself that Im Italian, but actually it is just that, a jokeagainst myself, more than anythingand I feel strongly that it is essential for me, in or out of the kitchen, to be authentic. What I am is an Englishwoman who has lived in Italy, who loves Italian food, and has been inspired and influenced by that: my food and the way I cook demonstrate as much.

So, no I dont claim that these recipes are authentically Italian, but authentic they are nonetheless. Food, like language, is a living entity: how we speak, what we cook, changes over time, historically and personally, too. As Ive said elsewhere in these pages: usage dictates form. It has to. Quite apart from there being something hopelessly reductive about endless discussion of whether some recipe may be considered authentically Italian or not, it doesnt make real sense. Not only has Italy existed for a relatively short time (since 1861, to be precise) but customs change and, while tradition is to be cherished, the way we cook must evolve. In fact, one of the aspects that is most admirable about Italians and their food is that they manage to safeguard their culinary traditionswith all their anarchic varietywhile remaining constantly interested in the new. (Not that this kind of culinary cultural embrace will surprise any Roman Empire obsessives.)