Contents

INTRODUCTION

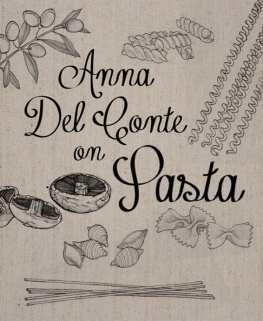

This book is a compendium of four little books I wrote years ago which were published in 1993 by Pavilion. These were: Antipasti, Pasta, Risotti and I Dolci.

The first three books contained my favourite recipes of dishes for which Italian cooking is justly famous.

I decided to write the fourth one, I Dolci, for the opposite reason, i.e. because dolci traditional Italian puddings, cakes, biscuits et al. are not well known in Britain and some of them are well worth knowing.

Because of its nature, this book contains many vegetarian recipes.

ABOUT THE BOOK

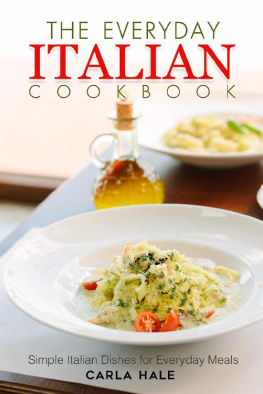

A classic Italian cookbook and essential for every home cook, Italian Kitchen brings together over 100 mouth-watering recipes for gleaming antipasti, earthy risottos, gutsy pasta dishes and sumptuous dolci into a bible of classic Italian cooking. Effortlessly stylish yet unfussy, they are the essence of any self-respecting Italian kitchen and provide the fundamentals of Italian cooking.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Anna Del Conte is the doyenne of Italian cookery. She has written twelve books including the acclaimed Portrait of Pasta, Gastronomy of Italy and Amaretto, Apple Cake and Artichokes. She has won the Duchessa Maria Luigia di Parma award and awards from the Guild of Food Writers and the Accademia Italiana della Cucina. In 2010 Anna received from the President of the Italian Republic the honour of Ufficiale dellOrdine al Merito della Repubblica Italiana and in 2011 Nigella Lawson presented her with the Lifetime Achievement Award of the Guild of Food Writers.

When I was taken out to dinner as a child I only ate lantipasto. The trolley would be wheeled next to me and I would be transfixed by the beauty of the food and bewildered by the choice. After a few decades I still feel like that. I want to take all the dishes home, admire them, and eat them slowly and thoughtfully over the next few days. First a taste of prosciutto, as well as culatello and felino, my favourite salami, which I would eat with bread and nothing else. Next would come a few floppy slices of grilled peppers, a curly tentacle of calameretti, and a morsel of each stuffed vegetable. Finally, a spoonful of nervetti in insalata Milanese brawn gleaming with olive oil and crowned with colourful sottaceti vegetables preserved in vinegar and speckled with purple olives and minuscule green capers.

Such are the delights of an antipasto offered in a restaurant. When you serve antipasti at home, however, you must be more selective and decide on two or three dishes at most. Otherwise you will be in the kitchen for far too long and begin to hate the idea of an antipasto for ever.

An antipasto can provide a good beginning to a meal, and it can even set the style for the meal itself. It is very important that, as an opening to the meal, it should be well presented and pretty to look at. It should also be light and fresh, so as to develop the taste buds for the courses to follow, rather than fill the stomach, and it should harmonise with the rest of the meal.

Nowadays an antipasto is usually a starter, no longer followed by a primo first course except on special occasions. For instance, if you have decided on a platter of affettato misto mixed cured meats a generous bowl of tagliatelle dressed with a vigorous sauce would make an ideal follow-on. So also would an earthy risotto or a gutsy spaghetti alla puttanesca with tomatoes, anchovies and chilli. This is not the traditional Italian way, but it is what suits our smaller stomachs and the preachings of the health gurus.

If, however, you are serving a joint of meat, start with a vegetable-based antipasto or a fish one. A fish antipasto, indeed, is the ideal precursor to a fish main course.

The recipes collected here are divided into six sections: Salumi, Bruschetta and Crostini, Salads, Stuffed Vegetables, Fish and Meat Antipasti, and Other Favourites.

Some of the recipes are for classic antipasto dishes, others are my own or those of my family and friends. All are typically Italian yet very varied. As varied, indeed, as most Italian cooking, because of the great differences between its many regions.

Antipasti

Salumi

CURED MEAT PRODUCTS

I know I am an unashamed chauvinist where food is concerned, but I am sure no other country offers such an array of delectable cured meats as Italy does. Salumi are usually made with pork or a mixture of pork and beef. There are also good salumi made with venison and various other meats. The mocetta from Valle dAosta is made with wild goat, the bresaola from Valtellina with fillet of beef, the salame doca from Friuli and Veneto with goose, and the salami and prosciutti di cinghiale are made with wild boar. This latter is one of the many glories of Tuscany.

The characteristics of the many types of salumi are determined firstly by factors affecting the pig, or other animal, itself. These include its breed, its habitat and food, and the climate of the locality in which it is reared. A prosciutto di Parma is paler and sweeter than, for instance, a prosciutto di montagna mountain prosciutto. Secondly, salumi differ according to which cuts of meat are used, the proportion of fat to lean, the fineness of the mincing, the flavourings and the curing. In what follows I describe some of the salumi that I like to serve as an antipasto. Together they form a dish called affettato misto, possibly the most common antipasto served in Italy. This dish of mixed cured meats is pretty to look at in its shades of pink and red, and one of the most appetising ways to start a meal. You may be serving the affettato before a dish of pasta. (This is where I should point out that the word antipasto does not mean before the pasta. It means before the pasto meal.) In Italy, however, affettato is often served as a secondo for lunch, not before but after the pasta that is de rigueur (only for lunch, though) in any self-respecting Italian family. Still, primo or secondo, affettato misto is an excellent dish, which, with some good bread or a piece of focaccia, followed by a lovely green salad and some cheese, is a perfect meal in its own right.

A good affettato misto should have a choice of at least five or six different meats. The following is a list of the products you can most easily find in Britain. You can mix them to your liking, but one type of prosciutto and two types of salami should always be included. With a prosciutto I put two or three different kinds of salami: one from northern Italy, a Milano perhaps, which is mild and sweet, a peppery salame from the south and a Roman oval-shaped soppressata. An alternative that I like is a fennel-flavoured finocchiona, a salame from Tuscany. A few slices of the best mortadella, speckled with the acid green of fresh pistachio nuts, and of tasty coppa, which is a rolled, cured and boned shoulder of pork, would be just right for a good assortment.

Next page