Acknowledgments

Many people have contributed to the making of this book and without their help I would never have achieved my goal.

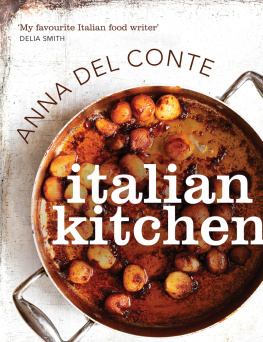

First I want to thank Becca Spry, the commissioning editor of Pavilion, who decided to republish my Portrait of Pasta which first came out in 1976. I liked the book very much and I am delighted to see it in print again. Grazie mille, Becca.

Then grazie mille to Emily, my new commissioning editor, for all her hard work in guiding me through the difficulties of what to delete and what to leave and what to add and what to correct.

The copy editor, Maggie Ramsay, has been invaluable in the production of this revised edition and if this book is coherent and makes sense, it is due to her. Grazie, grazie mille, Maggie.

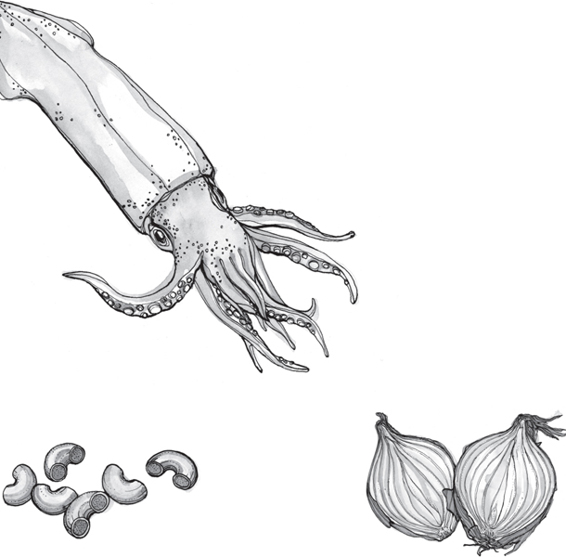

I am grateful to all the team at Pavilion, from Polly Powell, whose decision to republish my old Portrait of Pasta was essential, to Alison Legg, who produced the delightful illustrations and Laura Russell and Sophie Yamamoto, the designers, to Komal who has the task to make this book a best seller (if she is able to make miracles), and everybody else. A big Grazie.

Grazie to Vivien Green, my agent, who is always at the end of the line, both land and electronic, to listen to me, encourage and support me and give me the right advice.

And last, but certainly not least, grazie un milione of times to my daughter Julia and my grandchildren, Nellie, Johnny, Coco and Kate, for testing, cooking, tasting, discussing and being bored stiff by Nonna and her pasta dishes. But I know they enjoyed it as well especially the eating and now, I hope, this new book.

From the 1976 edition:

I should like to thank the following people for the help and encouragement given me in the writing of this book.

Ing. Vincenzo Agnesi

Dr Lella Mariani, Rizzoli, Milan, Italy

Dr Corrado Sirolli, Fara S. Martino, Italy

Dr Livio Zupicich, Industrie Buitoni Perugina, Perugia, Italy

Contents

Introduction

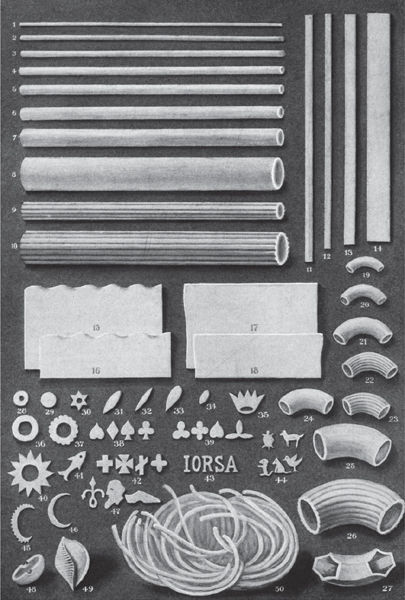

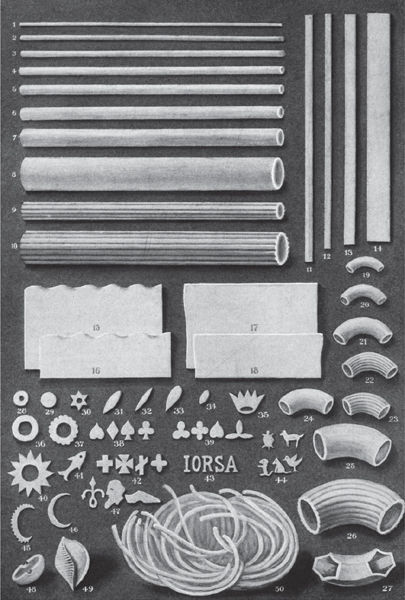

Pasta knows no barriers of class or wealth. In Italy it is a favourite with princes and peasants alike (there such anachronisms still exist), and elsewhere in the world it may be part of a banquet or a simple supper. Pasta knows no national barriers either. Although a national dish what other food is so strongly identified with one country? it is eaten all over the world. Pasta is the simplest food there is just wheat and water and yet it can assume a hundred different guises, from cream to curry, from spinach to sardines. It is also the most versatile of foods, for it can be a first course, main dish, side dish or even dessert.

So read on. Find out about Yankee Doodles macaroni, read the legends of miraculous macaroni, and discover what Lord Byron, Rossini and Sophia Loren have in common. And when you have read your fill, choose a sauce that suits your mood, boil up that saucepan of water and then, with due reverence, open up the package of pasta or reach proudly for the pasta you have made yourself.

What is pasta?

What is pasta made of? What goes into its list of ingredients? Flour and water, thats all. Except that the flour used to make dried pasta is ground from durum wheat. Durum wheat Triticum durum is one of the many varieties of wheat, another being common wheat Triticum vulgare from which bread flour is made. It is called durum, the Latin for hard, because its grains are far harder than those of common wheat, and when ground, they produce a substance called semolina. Semolina is not powdery like flour, but instead has the consistency of sugar, and is made up of sharp, hard, amber-coloured granules.

A place called Taganrog

Durum wheat has grown in countries bordering the Mediterranean since antiquity. In the nineteenth century, however, Russia was one of the main producers of durum wheat, and Russian durum was known as the best. There was a big export trade in durum wheat to Italy for pasta making, and this centred on the port of Taganrog, on the Sea of Azov, which is linked by a narrow strait to the Black Sea. The fine durum wheat that was shipped to Italy was known as Taganrog wheat, and was the only wheat used by the best Italian pasta makers.

Durum wheat began to be grown on a large scale in Italy during the Fascist years, when Mussolini set out to make Italy self-sufficient. As part of his Battle for Wheat, 809,000 hectares (two million acres), many of them quite unsuitable, were planted with wheat.

Durum wheat today

Major sources of durum wheat today are the great plains and prairies of the United States and Canada. The grain grown there is not only used on the American continent, it is also shipped to pasta manufacturers around the world.

Meanwhile durum wheat is still grown in Russia and in Mediterranean countries, with Italy remaining the major European producer. But then thats not surprising for a country that is far and away the largest consumer of durum wheat in the world.

Harvesting durum wheat on steep slopes in Tuscany, Italy.

Making pasta then and now

There is a pleasing simplicity about how pasta is made. In essence, the grain of durum wheat is ground, the resulting semolina is mixed with water to make a paste, the paste is formed into the required shape and then it is dried. There are, of course, many refinements and subtleties, but these basic processes have been the same since pasta was first made and eaten.

Streams and stones

Mills and grindstones seem to have been a feature of civilization since the beginning of time, certainly since man has eaten bread and pasta.

In Italy, the grain was washed in the millstream before it was ground. Women put the grain into wicker baskets, which they plunged into the water. Then they spread the grain out on the slate threshing floor to dry in the sun, and while it was drying they picked out the stones and other impurities.

Once dry, the grain was ground between two large round, ridged grindstones, lying flat one on top of the other. The bottom stone never moved, while the smaller top stone, which had a hole in the middle, turned on it. The grain was fed into the hole, and, when ground, it came out from the outer edge of the lower stone.

Modern milling

Today, the grains are still washed before grinding, but instead of wicker baskets there are carefully regulated jets of water. And instead of grindstones there are contra-rotating ridged steel cylinders into which the grains are pushed. At the end of the milling process, the resulting semolina still contains the husks and pieces of bran. To get rid of these, the semolina is purified in a device that uses air to separate the husks from the grain.

Next page