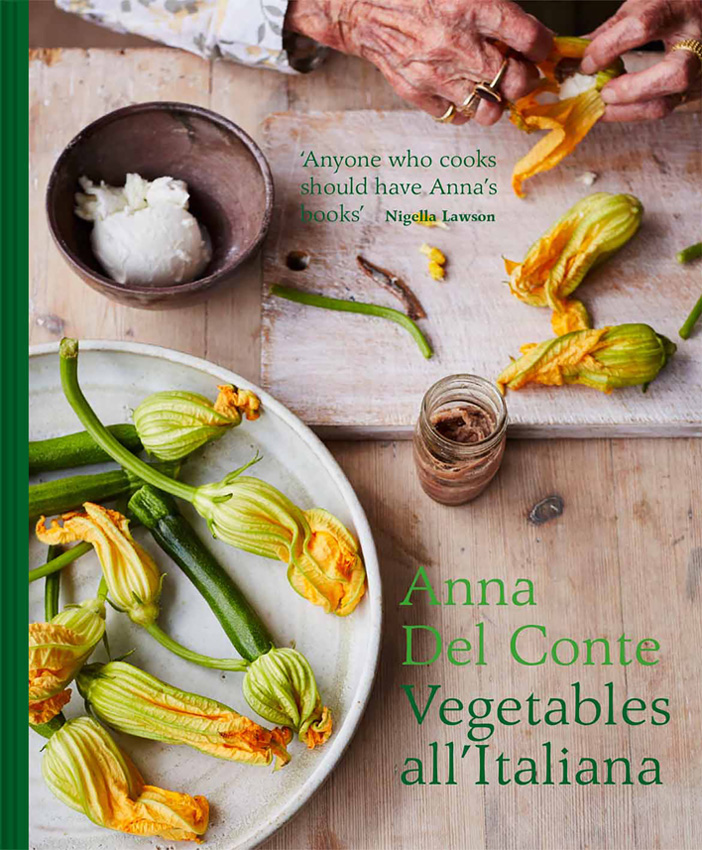

Anna

Del Conte

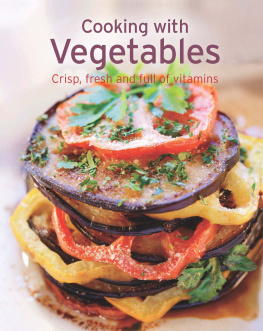

Vegetables

allItaliana

Verdure

Vegetables

This is a book on verdure or vegetables, where vegetables are treated with all the due reverence that they are in Italy, where they are never thought of just as an accompaniment to the main meat or the fish dish, even when they are served alongside.

As soon as I set foot in this country over half a century ago, I realised that the English view was that vegetables were just something healthy one should eat with the meat or the fish course. I know that at that time most people were not at all interested in food of any kind, and vegetables were certainly at the bottom of the list. I was lucky enough to land, as an au-pair, with a family where good food was appreciated and enjoyed. Kitty, my hostess, was a good cook and she excelled at baking at making pies and puddings, cakes and biscuits all extremely English. But when it came to vegetables, Kitty usually just boiled them, though not overso and that was it. They were very good vegetables, most of them coming to the kitchen straight from the large vegetable garden that her one-legged gardener was lovingly looking after. Occasionally, Kitty would make a white sauce to go with the vegetables. Otherwise they came to the table totally naked.

One day Kitty asked me if I could cook the carrots that were on the kitchen table, just dug from the ground. Yes, of course, and out I reached for the frying pan, a small onion, the bottle of the precious olive oil and the pack of margarine the rationed butter was kept for spreading on toast and bread. I scrubbed and washed the carrots and cut them in thin discs; and chopped a little of the onion. I put one or two tablespoons of oil and a lump of margarine in the pan and heated it. Then I added the onion and, when it was just turning a golden colour I chucked in the carrots and cooked them gently while adding a little stock every now and then. The stock was most probably chicken, from one of the local hens Kittys, the gardeners, or some neighbours, since everybody had hens at that time. Those carrots were one of my greatest culinary triumphs and yet they were simply cooked, allitaliana, in the everyday Italian way.

The vegetable scenario is now totally different. Vegetables of all sorts are widely available the whole year round, even too much so. I prefer to eat vegetables when they are in season as I was brought up to do. Now, for instance, I am writing this book in March, which is probably the least vegetable season-friendly month of the year. And in my larder living in an old house in the country, I still have the luxury of a larder there are a leek, half a Savoy cabbage, as well as the usual potatoes, carrots and celery. However, no courgettes, peppers or aubergines. I might have a tomato or two but certainly not for eating in salad, more for cooking whenever I need it. The other stand-by in my kitchen is frozen petits pois, which so often has saved me from a meal without vegetables. And, I nearly forgot, a fennel bulb. I dont know why I can eat fennel out of season; probably because they are never in season in this country, since they cant be cultivated here because of the weather.

The 132 recipes in this book will show just how much you can do with a vegetable. Some of these recipes are quick and easy, some are more demanding and complicated, but all are worth having a go. There are no pasta sauces and no risotto recipes here, because in these instances the main ingredient would be the pasta or the rice, not the vegetable.

It would be fair to say that most of the recipes are suitable for vegetarians and even the non-vegetarian recipes can easily become vegetarian with a slight tweak of the ingredients. For instance, in the recipe for , you can omit the pancetta and add instead a little more oil; and there are a few recipes containing anchovies or tuna, or perhaps a little meat stock, which can be adapted if necessary, but, for the most part, the recipes are vegetarian.

Most of the recipes are for four people. However, some recipes are for more because the dish can only be made successfully in larger quantities. The serving quantities can only be a guidance because other factors have a role to play. Are the people who are going to eat that dish young or old? Is that their only meal of the day? What is coming before or after the dish in question? I usually err on the side of plenty; I prefer to have left-overs, than to see my guests scraping the last spoonful of the dish.

When you follow a recipe, use just one system of measures metric, imperial or cups all through the recipe. All spoons are meant to be level. 1 tablespoon = 15 ml, 1 teaspoon = 5 ml. A set of measuring spoons is a great help to a cook. A set includes 5 spoons which measure from a pinch to 1 tablespoon.

My recipes are only a guide. Read them, cook them once or twice and then give them a slight twist, your own signature. Make them part of you, as your food is. You will enjoy cooking far more if you dont stick literally to the gospel of a recipe book. However, it is important to pay attention to the proportions of the ingredients used. This will teach you to achieve the Italian flavour, and having learnt that, you will no longer need to follow a recipe slavishly. I would also stress that good cooking requires precision, care and patience. Creativity comes later, just as in any other art.

Notes for the reader

My English friends have suggested that I should include some of the little points that crop up in my conversations with them and which, they say, are often unfamiliar to the non-professional cook. So lets start by giving an explanation of some of the Italian culinary terms I use.

Battuto is a pounded mixture (the word comes from battere to beat or pound). The battuto is the basis of most dishes, from a pasta sauce to a bean soup. Nowadays a mixture of olive oil and butter are used instead of pork fat, with possibly a little pancetta or prosciutto. When I add pancetta or prosciutto I use a food processor, which does an excellent job in a whizz. A battuto usually becomes a soffritto, except when it is added a crudo (in the raw state) to a sauce or a soup.

Soffritto is the battuto which has been fried, or actually under-fried, which is what the word means. The battuto is sauted in a saucepan or a frying pan over a gentle heat until the onion is soft. When using garlic, this should be added to the onion later, when the onion is nearly done, or the garlic will become too dark by the time the onion is soft. Only when the battuto contains pancetta or fatty prosciutto can the garlic be added at the same time. A well-made soffritto is fundamental to the final taste of the dish.

Here are some of my tips, arranged in alphabetical order.

BUTTER

I always use unsalted butter it has a more delicate flavour and can be heated to a higher temperature than salted butter. To heat butter to a higher temperature without burning, I add some olive oil.