Thank you for purchasing this Gun Digest eBook.

Sign up for our newsletter and receive special offers, access to free content, and information on the latest new releases and must-have firearms resources! Plus, receive a coupon code to use on your first purchase from GunDigestStore.com for signing up.

or visit us online to sign up at

http://gundigest.com/ebook-promo

For

James Guthrie

1975 2013

No Better Friend

INTRODUCTION

The shotgun is the oldest of firearms, the most widely used in the world today, and the most useful and versatile overall. A shotgun is also the most fun to shoot.

Historically, shotguns have also been referred to as smoothbores, to differentiate them from rifled firearms, and also scatterguns, to denote shot that scatters in a pattern, rather than a firearm that fires a single projectile. By whatever name, shotguns have myriad uses: Hunting both large and small game, self-defense and tactical applications (including use by police and military), and a wide variety of games and sports from informal hand traps in the backyard to Olympic competition.

Obviously, a gun intended for any of these purposes is not necessarily suited to others. A typical gun for rabbit hunting on a farm, for example, is not ideal for shooting Olympic trap. Having said that, we must also add that a single shotgun can be made to do more things well than can any other type of firearm; there is such a thing as an all-around shotgun that allows its owner to participate in many different activities and to turn in good performances in all of them.

With so many varieties and with shotguns made for a host of activities in many different countries, the newcomer looking to buy a gun can be forgiven for feeling completely lost. Even shotgun veterans can be confused by the myriad guns and configurations now available, to say nothing of the variety of shotshells for them.

This guide is intended to help sort them all out: to assist a father in buying a first shotgun for a son or daughter, whether for hunting or to participate in collegiate shooting sports; for a new shotgunner to purchase the right gun to start with; or for a shooter with some years under their belt and a desire to move into other disciplines and procuring the right second or third gun. We hope even shotgunners of many years experience will find this book interesting and informative. With shotguns, there is always something new to learn, a different activity to master, a different skill to polish. Thats what has made shotgunning popular for 200 years, and its what keeps us all coming back.

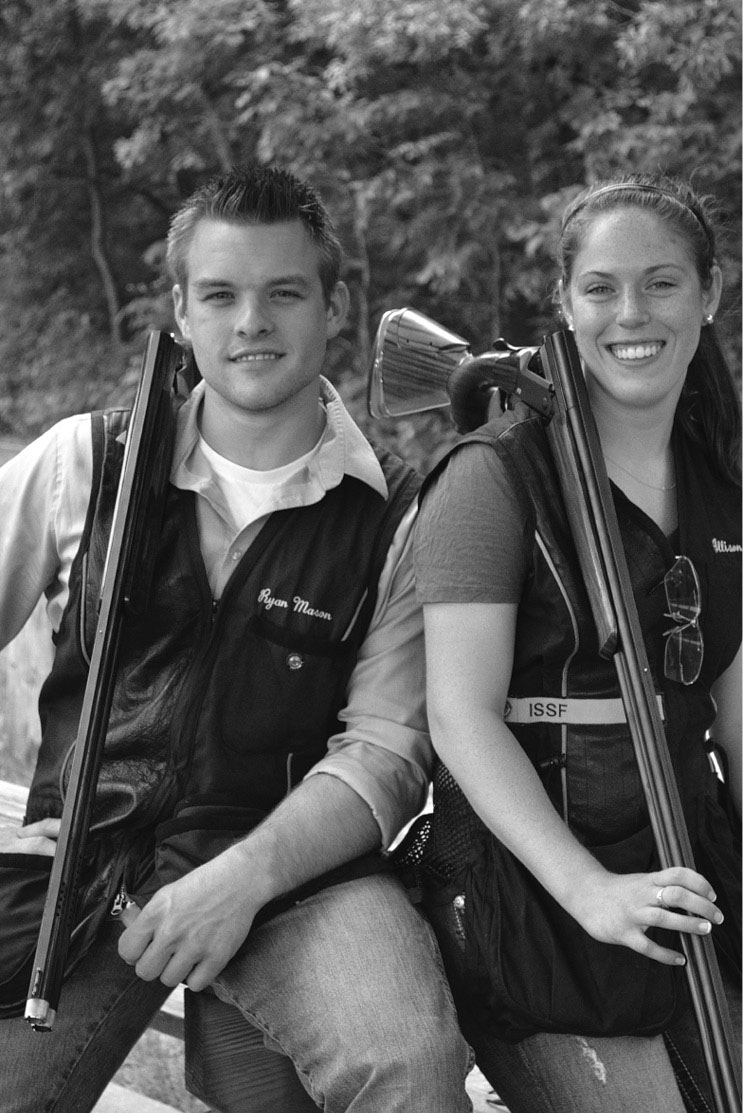

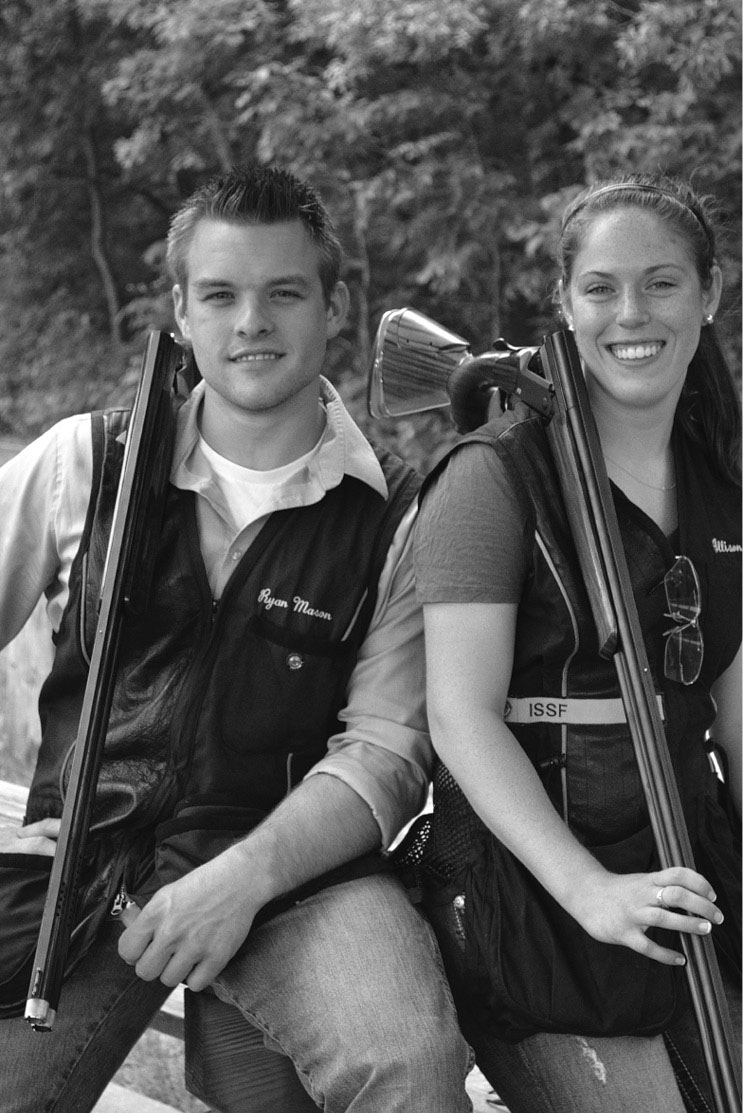

Missouri shooters Ryan Mason and Alison Caselman compete in skeet, trap, and sporting clays. They appear throughout this book demonstrating guns and techniques.

CHAPTER 1

THE SHOTGUN IN HISTORY

What is a shotgun? Very simply, a shotgun is a firearm that shoots many small projectiles at one time. Unlike a rifle, which seeks to place a single bullet in an exact spot on the target, a shotgun fires a charge of round-shaped pellets that expand in a cloud as the charge leaves the muzzle. While the rifle is a long-range weapon, accurate out to several hundred yards and beyond, the shotgun is used at short range and is normally effective from 20 to 60 yards at the most. Unlike other firearms, the shotgun is intended for use primarily on moving targets, such as a flying bird or a running rabbit.

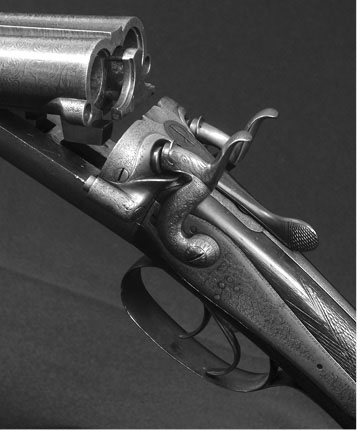

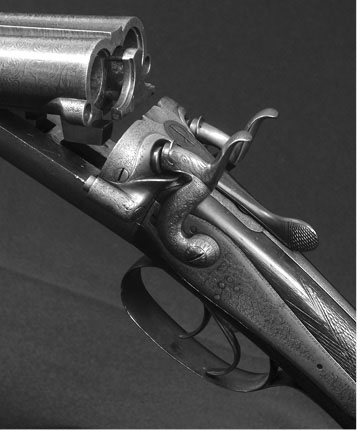

An early break-action hammer side-by-side shotgun, by Holland & Holland.

Although its exact origins are lost far back in time firearms have been with us for about 800 years the shotgun was certainly one of the very earliest firearm forms. The shooter would pour some gunpowder down the barrel and then drop in anything that came to hand, from pebbles to scrap iron. All early firearms were very short-range propositions, and such shrapnel could be extremely effective.

Early guns were very crude. Although some were intended for firing while held in the hands, they were constructed with neither accuracy nor convenience in mind. The barrel was a piece of pipe, the stock merely a chunk of iron or wood that served as a handle. The refined technical features of a gun we now take for granted, including the stock, the lock mechanism for firing, and the trigger to trip the lock, evolved over hundreds of years.

The story of firearms development has filled hundreds of books, and we dont have space here for any but a quick look. However, to understand the shotgun as it now exists, as well as the demands it places on the shooter, it is useful to know how it works and why.

The force used to propel bullets or pellets out of a firearm is provided by expanding gases. These gases come from burning gunpowder, either the original blackpowder or todays smokeless propellants. There are similarities and differences between the two, but the basic principle is the same: A flame is applied to the gunpowder and, as the gunpowder burns, it creates gas that expands rapidly, applying pressure to the projectile and hurling it out of the muzzle at high speed.

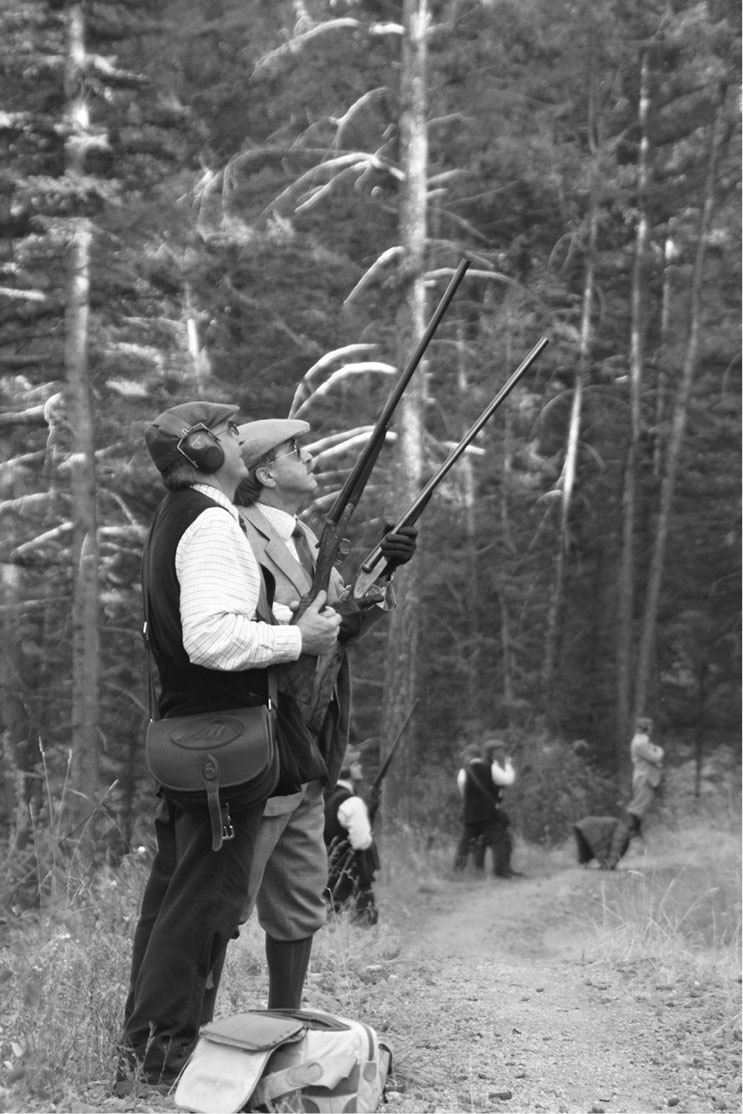

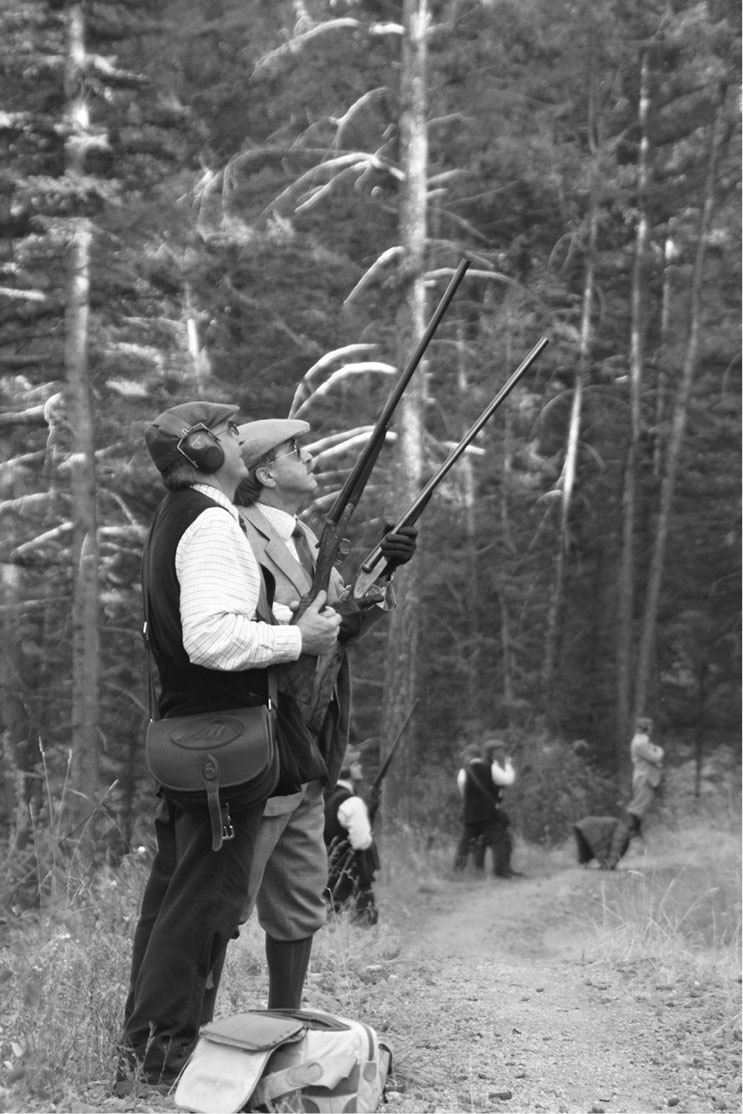

The development of driven shooting in England also drove shotgun development. Here, the guns wait for pheasants, at a shoot in Idaho.

Some early implements used to load blackpowder shotshells. Todays cartridges are, of course, much easier to use.

Gunpowder is not an explosive in the technical meaning of the term. Smokeless powder, such as we use in modern shotshells, is correctly called a propellant. Different powders are used for different purposes, mostly based on burning rate. The pressure peak in a modern shotshell is in the neighborhood of 10,000 pounds per square inch (psi). Obviously, such pressures can be very destructive, if not confined by good steel. For this reason, shooters must be aware of the loads they use in their guns, and handloaders (those who load their own shotshells), must ensure they use the correct powder in the proper amount.

To anyone familiar with pressures and how they make things function in everything from cars to hydraulics, it is obvious you cannot simply pour some blackpowder down a gun barrel, throw the lead pellets in afterwards, and expect to fire a shot. The expanding gas would blow right through the pile of pellets. A device was required to create a seal between the gunpowder and the shot charge, to confine and direct the pressure. In muzzleloaders, this was done with a cloth or paper patch called a wad.

The other major problem back a couple centuries was in how to ignite the powder. The early methods of the match- and wheellock, which used a smoldering fuse to touch the powder, were eventually replaced by the flintlock. In that mechanism, a piece of flint is held in a hammer. When released by the trigger, the hammer swings forward and the flint strikes steel, creating a rain of sparks, and these ignite a small charge of gunpowder in a part called the pan. Flames then flash through an opening in the barrel, the flash hole, igniting the main charge of gunpowder.