All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission of the publisher.

Several passages in originally appeared in an earlier form on AlterNet and Nerve, respectively.

Published by Akashic Books

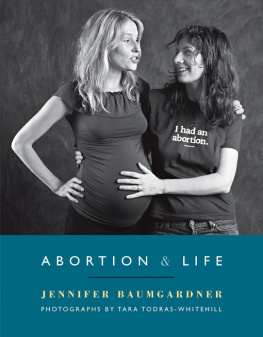

2008 Jennifer Baumgardner

Photographs 2008 Tara Todras-Whitehill

ISBN-13: 978-1-933354-59-0

eISBN-13: 978-1-617750-39-7

Library of Congress Control Number: 2008925930

All rights reserved

First printing

Akashic Books

PO Box 1456

New York, NY 10009

info@akashicbooks.com

www.akashicbooks.com

There is no agony like bearing an untold story inside you.

Zora Neale Hurston

The defensiveness that the pro-choice movement has is well-earned.

Weve been shot at, picketed, fought every step. But Im very glad

that the conversation is changing.

Loretta Ross

For Barbara Seaman (9/11/352/27/08), who really listened

Acknowledgments from Jennifer

This book couldnt have come together without the help of the following people: Amy Ray, Merle Hoffman and the Diana Foundation, Gloria Browning, Karen Burgum and the F-M Area Foundation Womens Fund, and Roberta Schneidermanall are incredibly generous women who underwrote the research of this book. My friend Gillian Aldrich directed the documentary that was the cornerstone of bringing the I Had an Abortion project into being; many of Gillians interviews are threaded through this book. Rebecca Hyman kindly allowed me to reprint her article about the abortion T-shirts. Conversations on the History in Action listserv provided inspiration, personal stories, and clarity. Merle Hoffman, Constance DeCherney, Soraya Field Fiorio, and Dea Goblirsch read drafts of the text, and Rebecca Davis helped write the resource guide. Intrepid photographer Tara Todras-Whitehill suggested that we use her stunning portraits as the basis for a book; Akashic Books publisher Johnny Temple (a man with integrity to spare) had instant and enduring faith in the project. My deep gratitude goes out to all of the above and to the many women and men who agreed to share their storiesin particular Amy Richards, whose insights continue to evolve my thinking on many issues. Finally, it goes almost without saying that my open-minded familySkuli, Mom and Dad, and Andrea and Jessicaenable my work on a daily basis. I thank all of the above for their good humor, brains, and honesty.

Tara thanks

My parents for their constant support, even when they werent sure what I was doing, and especially my mother for being my first subject on this project. My wonderful friends and familyfor their encouragement, energy, and faith in my work, without whom I would have given up long, long ago. Patrick McMullen and company, for donating their studio space and lights for these portraits. Modernage, for making such beautiful huge prints of the women. Ken Regan, for being a great photographer, friend, and mentor to whom I will always be grateful. All the people who donated to the creation of the prints so that people could see the women life-sized and eye-to-eye. Jennifer Baumgardner, for seeing the potential of this project and incorporating it into her own without hesitation; additionally, seeing Jennifers energy and passion about womens issues was instrumental in helping me focus on what was important in my life at a time when I was really searching for direction. And finally, the women who allowed me to photograph them: I cant thank them enough for letting me into their lives and for being such strong role modelsthey are an inspiration to me and I hope to everyone who sees their pictures.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Portraits and Stories of Women Whove Had Abortions:

.

I dont remember when I first heard the word abortion. What I do recall is this: By age four I knew, generally, how babies were made because my mother became pregnant with my sister Jessica and insisted on explaining to us, in the most clinical and explicit terms possible, about vaginas, sperm, eggs, and intercourse. My parents werent hippiesfar from it, in fact, having been raised in small-town North Dakota during the 1950s. I too was raised in North Dakota, but I was a child of the 1970s and my youth was colored by the cultural movements of the time, including feminism.

The second wave of feminism ushered in consciousness and discussion about birth and bodies, as well as a womans right to control both of these things herself. My mother recalls showing my Grandma Gladys the photos of childbirth in Our Bodies, Ourselves and Grandmawho had given birth to eight children, three when she was still a teenagersaying that she had never glimpsed a babys head crowning out of a vagina. She was fascinated. We had Ms. magazine in the house, with its frequent headlines about reproductive freedom, and I think I absorbed what ending an unwanted pregnancy was before anyone ever talked to me about it.

The first real conversation I had about abortion occurred when I was ten and my family was visiting friends in Iowa City. The mother in that family, Laurel Bar, was a strong feminist, intense and intimidating to me at that age. Laurel had two identical pins the size of half dollars on her kitchen bulletin board, both depicting the pro-choice symbol of that generationa wire hanger with a red bar struck through it. I was intrigued and asked if I could have one. She held a pin out and looked me right in the eye. Ill give this to you, she said sternly, but only if you wear it and understand what it means. Her intensity made me momentarily nervous, but at the same time, I was flattered that she was taking me seriously. I took the button from her, and I took its message to heart. The point of that button was, of course, the assertion that a woman should never be forced to thrust a hanger through her cervix and into her uterus because she is pregnant and has no access to a legal abortion.

For Laurels generation, for Laurel herself, this hanger meant something literal. Laurel was the sole confidante (with the exception of the girls mother) to a friend whod had an illegal abortion in 1964. The girls mother, who insisted that the father could never find out, had found the abortionist and taken her terrified daughter to an actual back alley to meet her fate. After the abortion, the girl bled copiously. Six years later, Laurel flew with another pregnant friend to New York City, this time for a legal abortion. The difference was staggering, Laurel now recalls. The second friend just walked out of the clinic, came back to the hotel, and was completely fine. No secrets; no hemorrhaging.

For my generation in the United States, though, the hanger doesnt evoke memories of barriers that women faced. The image is abstract, not quite relevanta marker of another time and, despite claims to the contrary, not likely to be part of our future, even if Roe v. Wade, the 1973 Supreme Court decision that made abortion legal in all fifty states, were to be overturned.

A current symbol of reproductive freedomwhat would that be? A gun with a strike through it to represent the clinic violence that marked the 1980s to mid-90s, killing three doctors and four other clinic workers? The fleshy pink faces of Senator Jesse Helms and Representative Henry Hyde, both of whom signed into law restrictions that mean poor women have very limited access to early abortion and birth control information? Angels wings, to indicate the thousands of women who have abortions and yet believe that a fetus has a soul and is watching over them? Or an open mouth, to illustrate the growing movement of women who are speaking out about their abortion experiences, from the after-abortion counseling groups like Backline and Exhale to the zine

Next page