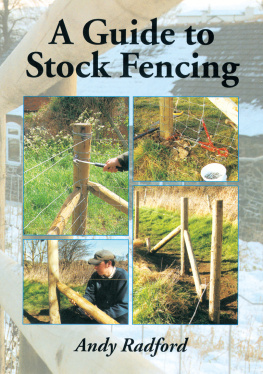

A Guide to

Stock Fencing

Andy Radford

First published in 2002 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

Paperback edition 2013

This e-book first published in 2013

Andy Radford 2002

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 84797 614 7

Dedication

This book is dedicated to Emily, Jamie and Crisiant, my three beautiful children.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank those individuals and organizations who have supported me throughout the writing of this book.

ETC Saw Mills of Ellesmere, Shropshire and Chirk, for their kind sponsorship of materials and information; Colin Heskins, Martin Roscoe, Ian Nash, Russell Williams, Dave Lippet, Ray Parry and Derek Wellings of ETC, who offered useful retail advice; Peter Farmer of Uniwire for supplying information about stock fencing products; Peter Hardwick, Pam Pickering, Graham Phillips of the Peak District National Park Ranger Service; Neil Symon; and Glyn Jones, John Vidal, Ade Wood, and Karen and Susan Harper whose projects are featured in the book; Roger Gardner, Stacey Barlow, Dan Wilson and Lee for helping with the projects described here; and last, but not least, my partner Janet Williams for proof reading, help and support.

PREFACE

Along with dry stone walling and hedge laying, stock fencing is one of the major agricultural and domestic tasks I carry out during the course of my work. I say domestic because many a hobbyist livestock owner and smallholder calls on my skills either to erect a stock-proof barrier or just to ask for my advice on material requirements and the techniques of my trade. Although the latter practice holds the danger of my losing valuable custom during the lean winter months, I tend to give this advice freely in order to help a fellow countryside and animal lover.

Like dry stone walling and hedge laying, I acquired my fencing skills seventeen years ago, working first as a volunteer and then as a full-time employee of the Peak District National Park Authoritys Ranger Service. I left the National Park in 1991 and eventually set up my own organic landscaping business. My work today encompasses a wide variety of projects from repairing a small section of wall on some idyllic, lonely mountainside, to building fences that enclose sheep or cattle or to complete garden enhancements with a full wealth of features.

Most of my work is carried out in the mountains of the North Wales borders; but the seed of my trade germinated in the Peak District, a fact that I shall never forget, and I shall be forever grateful for the National Parks time and professional tuition. Luckily, I can now pass on these skills through the written word, with the hope that they help you to enjoy working in the serenity of the great outdoors as much as I do.

INTRODUCTION

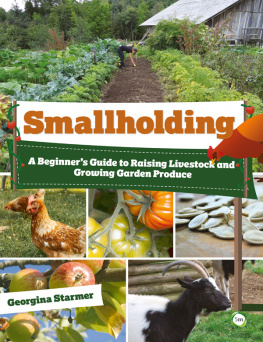

To a smallholder, a strong, stock-proof enclosure is just as important as the animal it is designed to hold. The two are, without argument, inextricably linked. Goats, sheep, cattle and ponies are, by nature, expert escapees or fence bulldozers. Quite often the discerning stock-keeper will have an on-going, sometimes frustrating battle if an animal has a mind to persistently break out. It is not much fun watching your cherished goat wander on to next doors land with the sole intention of eating your neighbours shrubs, lovingly grown vegetables or precious flowers. And the last thing we all want to see is our specially bred ewe straying on to the road only to be mown down by a passing vehicle. The majority of such incidents usually occur with jury-rigged fences piecemeal enclosures built out of reused fencing materials, old bedsteads, wooden pallets or anything else that can be found about the yard. This type of fence, I have to say, is all too common.

There is much to be said about a strong, well-built stock fence specifically designed to the characteristics of the animal it is intended to contain. Understandably, the main reason for a jury-rigged fence is financial. The outlay for new materials can be expensive, but this has to be balanced with the costs of having to continually repair and maintain a weak boundary, insurance claims from neighbours and road-kill. Using new materials, a correctly built enclosure can have a life span of between fifteen and twenty years, with little or no maintenance at all. This, in the long run, saves money and leaves time for the smallholder to get on with other important business, secure in the knowledge that his livestock is well protected.

Ever since human beings discovered agriculture the need for durable fences has been of paramount importance. Ancient farmers based their enclosures on their house building styles, using a wattle and daub technique. Woodlands containing hazel and birch were coppiced. Coppicing is a process of farming trees whereby they are felled, leaving just stumps. The stumps then sprout new growth, usually in the form of straight, thin trunks. The trunks formed poles that were then harvested for the construction of fences and dwellings. The farmer then inserted the poles into the ground to act as uprights for thinner branches that were woven in between. The fence was then daubed with mud or clay.

Almost all of the worlds ancient peoples used wattle and daub in their everyday lives for their boundary construction. Examples of this may found rooted deep in a nations history. The stock fences of the Celts, the dwellings of the Aboriginal peoples of Australia, many ancient Greek and Roman structures and even the medieval hill forts of Britain and the military enclaves of the Wild West were erected using a similar technique.

It is plain to see that the art of stock fencing has an absorbing, colourful past, and one that can easily rival dry stone walling or hedge laying. The only things that have changed are the qualities and the styles of the materials used. Whereas the life span of a wattle fence was a hit and miss affair, todays components are manufactured to the highest standards by the use of computer software for cutting and shaping. Modern wood treatments add precious years to a finished product by fighting the effects of damp, decay and fungus. In the same way, galvanized fencing wires and fittings ensure rust protection for the rough years ahead.

Raw material in sawmill.

From Sustainable Forest to Sawmill

In Britain the wood for fencing materials is collected from purpose-planted conifer plantations. The trees, including larch, spruce and Sitka are harvested through a process of sustainable forestry. This means that for each tree felled another is planted in its place, ensuring a crop for the future. Although most of these species are imported from Scandinavia and are therefore not indigenous to the British Isles they, none the less, form attractive additions to our countryside and a stroll through a mature plantation can be just as invigorating as an early spring morning. The red squirrel, now very rare, has found a safe habitat within the pine forests of the North, away from the common, foreign grey squirrel, and a host of other creatures have sought sanctuary within these closely planted trees. But like them or not, these trees are here to stay and have now become an integral part of the British countryside. Furthermore, they are the first choice when it comes to building modern stock enclosures.

Next page