This book is for anyone wondering whats in their food.

Contents

Introduction

Almost everyone eats processed food. Even the most devoted pure-food fan smokes, pickles, freezes, or cooks foodthe most basic forms of preserving food that have been with us since the dawn of mankind. However, many of us are more curious than ever about the food ingredients that dont seem like real food: the additives (those things with the long, unfamiliar, and complex chemical names listed on food packages). This interest may have something to do with the fact that additives are mostly not real food. They also catch our attention, in part, because we dont know what the heck the names mean and, in part, because, lets face it, they simply seem scary.

We hope to address that uneasiness with this unique book. Dwight and I are often amazed by items we find among the daily elements of our lives, and love learning about them. We have some other things in common, too, like our insatiable desire to know whats actually in our food.

Raised on homemade wheat-gluten patties and scrambled tofu colored with turmeric to resemble eggs, processed foods were out of Dwights reach for the first part of his life. After trading the safety of his mothers kitchen for a college cafeteria, he loosened up a bitnot so much that he substituted all of his fruits and vegetables with processed foods, but enough that whole foods shared the plate with many of the usual processed suspects of the standard American diet. Once he became a father, he began to think about food analytically for the first time. As a successful advertising and editorial photographer, Dwight took his inspiration for food deconstruction from conversations about food ingredients on photo sets with an inspired chef and a talented stylist. He sought to combine his curiosity about food with his obsessive-compulsive nature, which eventually led him to me.

I have worked as an assistant chef, lived in Paris, where I found myself eating at top restaurants as part of my work, and have written several books on food-related subjects. As I researched the origins of various foods, especially the ingredients in ethnic cuisines and beer, I began wondering about artificial food ingredients and took up the habit of reading labels very closely. When my young children, who mostly ate whole foods, started quizzing me about the processed-food labels I was staring at, I realized that the way to do an in-depth investigation on the subject was to deconstruct the ingredient label of a well-known processed-food product. I soon settled on Hostess Twinkies and wrote a book, Twinkie, Deconstructed , about where all the Twinkies ingredients come from, how they are made, and what they do. I like digging into the details behind complex but common things. Instead of taking photos, though, I took trips to the mines, factories, and labs to see for myself the sources of such food additives.

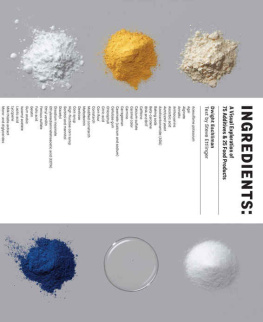

One day I saw an enormous spike in my Web site traffic, which I found was linked to Dwights self-published project, 37 or So Ingredients , a collection of photographs of Twinkies ingredients that had gone viral. Thus art, science, and the loves of wonderment and deconstruction inspired Dwight and me to join together to create this visual representation of the food additives that are found in the ingredient lists of common processed foods.

About Food Additives

Anyone who cooks knows that you must almost always process food somehow to eat it. Unless you are a grazing animal, at a minimum, you clean it or you cook it. But industrial, massmarket, commercial food producers add things (additives) to food (basic foodstuffs) or even packaging for at least one of four reasons: to make the food product more nutritious, to make it easier to prepare, to make it more appealing, or to make it stay fresh longer.

The ingredients in our book are additives that fill at least one of these functions; some fill several (the Food and Drug Administration lists seventeen subsets of functions []). Some replace foods that are prone to spoilage, such as fresh eggs. Others, such as various corn syrups, replace foods that might be more expensive, such as sugar. Some, such as the vitamins in enriched flour, replace the natural ingredients that were removed in processing. Others simply add a healthy one. And many are there to somehow extend a products shelf life, the holy grail of food product manufacturers. They all are part of the creation of what consumers perceive as inexpensive, convenient foods.

When you bake a cake at home, you dont use most of the additives shown here. You might mix a batter with more elbow grease for one recipe than another; you might refrigerate or warm up various ingredients (such as butter) to make them blend more easily. You might cover a stored item tightly to make it last longer in the fridge without drying out or spoiling. You might form the top so it looks nicer. You might buy a special cupcake transporter box to protect your goods. But you dont need any additives to do these things.

On the other hand, when you bake a cake or make some commercial food product by the millions in a large factory with industrial machinery and ship it around the country, where it sits on store shelves for weeks, you might add something to a batter to make it easier to pump through hoses. You might add something to keep the bubbles in a batter from getting crushed at the bottom of an enormous kettle. You might add something to keep the final product from losing moisture or flavor in storage or so it doesnt collapse during transit. You might add something or use special ingredients so it doesnt spoil quickly. In short, you use food additives to achieve the scaled-up goals that the home cook addresses quite differently.

Since World War II, the availability and use of food additives have evolved considerably, especially recently. The war created demand for chemical research; the postwar economy created demand for convenience foods. These days, consumer demands tend to focus on carefully created food products that deliver certain health benefitsso-called functional foods such as high-fiber, low-fat, and no-sugar products. The result is food products filled with more and more additives and much longer and more complex ingredient lists. It can get quite confusing.

About Food Product Labels

Food additives come with a lot of baggage. Related terms are often obtuse. This stems from the fact that their names are a mix of scientific and cultural traditions, that they must be approved by a variety of outfits, and that they are regulated by a variety of rules and laws across borders. Food additives receive approval only after years of testing and correspondence with the authorities (dietary supplements are not FDA-regulated), but some considered safe in one country are banned in another. Some of that irregularity stems from cultural and political differences and some comes from the relative influence of the food industry. Research is vetted by disparate groups, including the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, the World Health Organization, and the Codex Alimentarious Commission.

Hidden from the common shopper are regulations concerning allowable amounts of an additive in a food product. Some are restricted to a minuscule parts per million (ppm), while others, having been in use for years, earn the vague classification of GRAS (Generally Recognized as Safe) and are limited to doses defined even more vaguely as good manufacturing practices.