T he connection between flesh and bone is primordial and fundamental. Yet today, bones have fallen out of favor. We are all familiar with the expression, The nearer the bone the sweeter the meat, but we demand everything precut and prepackaged, and that is, increasingly, all we can buy. Our world is full of recipes for boneless, skinless (and often tasteless) pieces of meat, chicken, and fish, and we scarcely recognize whole fish or birds. We have become so obsessed with ease of preparation and speed that we have lost touch with the visceral appeal of cooking withand eatingbones. No carcass to cut around, no whole fish to fillet awkwardly. When was the last time, other than Thanksgiving, you ate a meal that was carved at the table? Carving has become a lost art.

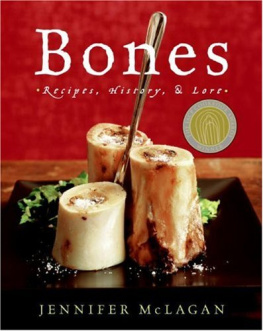

My passion for bones was rekindled during a wedding anniversary dinner several years ago, at a well-known Paris restaurant. The evening began tentatively, with my furtive glances at the man seated at the next table. No, I wasnt plotting a change of mate, I was envious. Envious of this strangers bones: a plate of three towering marrow bones, each crowned with a different topping. I wanted those bones. Luckily, my husband is patient man who shares my passions. There was no need to stray, we celebrated with our own plate of bone towers. As we scooped their soft, creamy centers onto toast, dusting them with salt, I reflected sadly on how such a simple, indulgent pleasure was vanishing.

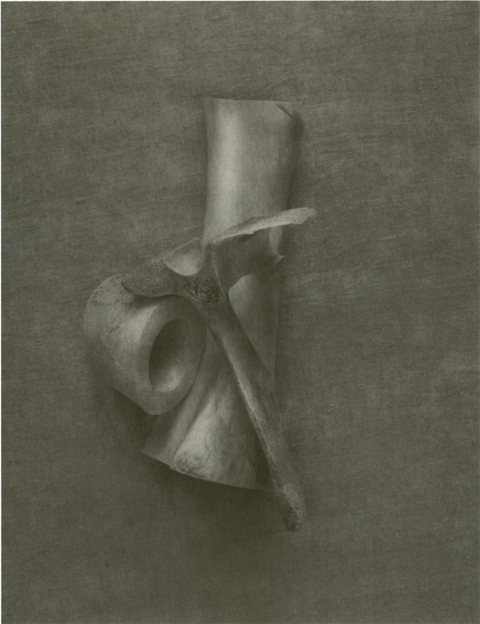

Not just marrow bones, but all bones are disappearing from our kitchens. As bones fade from our consciousness, the ways in which they enhance and improve the food we eat are forgotten and ignored. But bones play an integral role in the art of cookery, adding taste and texture while enhancing the presentation of the food. Think of osso buco, rack of lamb, fish grilled on the bone, spareribs, roast chicken.

The food of my childhood was enriched by bones. Every Friday morning, my mother and I crossed the butchers sawdust-covered floor, joking with the ensemble of jolly, big men in long white aprons. We passed the refrigerated counter, with its carefully arranged cuts of meat, and headed directly for a side room where whole animals hung suspended by metal hooks. Entranced, I watched as the butcher skillfully cut an animal into more familiar pieces. After much earnest discussion, we would leave with an assortment of meat with its bones. Once home, bacon bones were transformed into thick pea soup, while oxtail was slowly braised with red wine until the sauce was so rich and sticky it glued your lips together. Irish stew was made with lamb shoulder chops layered with thickly cut potatoes, which readily absorbed the lambs flavor and fat.

Once I began to travel, I discovered more exotic bones. A warming bowl of pho, beef soup, shared with three old Vietnamese women on a rainy, damp market day in Hue, brimmed with the aromas of long-cooked beef bones and star anise. In Italy, I relished a tiny songbird, bones and all, much to the horror of my companions. The little bird, impaled with toothpicks to a piece of toast, had been deep-fried until the bones were so soft they dissolved in my mouth. All that remained uneaten was its beak. In Berlin, fork-tender, juicy Eisbien (pork hock) crowned a massive platter of sauerkraut.

I am often in France, where bones are still revered. I eat lip-smacking pigs feet, sucking the meat from the many small bones. In the spring on the banks of the Sone, in Burgundy, tiny fish are passed quickly through flour and hot oil, eaten like French fries, their bones so tiny you simply crunch them up. The highlight of a stay in Provence is whole rougets grilled with wild fennel.

So appreciated worldwide, bones and many of the cuts containing them are often overlooked in North America. The pigs feet at my local Toronto farmers market spark only the interest of recent immigrants, and my butcher gives away his veal bones. (He confides to me with regret that he rarely buys whole animals anymore because he cant sell the odd parts.) Why dont we buy these tasty, often cheap, cuts? Because we no longer know how to cook them and have forgotten the recipes for them. I had to write a book to help solve the problem.

Restoring bones to their deserved place in our kitchens will not be easy. First, we must fight against the current fascination with fast and quick, boneless food. Then we need to familiarize ourselves with the whole animal, its essential structure. When we understand where the bones are, we will be able to cook the meat attached to them. And, in a world where resources are increasingly limited, we must learn to value the entire animal. A cow isnt just tenderloin steaks, and there is more to a chicken than boneless breasts. We pay for the bones that are, or were, part of each piece of meat, poultry, or fish we buy, whether we use them or not, so why not benefit from them? Finally, we must seek out knowledgeable, caring suppliers and support them, badger them, and implore them. The more we ask for different cuts, the more they will become available again.

Chicken soup is a simple example of the importance of bones. With only a chicken, a few vegetables, and water, you can make a rich, nourishing broth that jells as it cools. Why? The chickens bones. Those bones add body and substance to the soup, as well as taste. Likewise, bones are the starting point of stock, an essential building block in the kitchen. While its true that stock is not quick to make, it essentially cooks itself. Preparing your own stock gives you control over the ingredients, and the results are far superior to anything you can buy. Stock can be made ahead and frozen, and it can be concentrated, so that it is easy to store. With stock on hand, you have the foundation of delicious sauces and great soups.

Cooking with bones can be homey and reassuring or challenging and inspiring, and Ive included recipes here to suit every palate and skill level. The adventurous can tackle marrow bones and pigs feet, or discover a classic dish with a modern twist, perfect for a dinner party. The occasional cook will find easy, slow-cooked comfort food, and a use for that leftover poultry carcass she or he might otherwise be inclined to toss. There are practical advance-preparation tips, and suggestions for alternative flavorings that make the recipes flexible.

When you cook with bones, you will be rewarded with a wonderful aroma permeating your kitchen, a delicious meal, and the accolades of your guests or family. An added benefit is that many of the dishes improve with keeping and reheat well.

Bones connect me to my childhood, and they link all of us to our past. As I researched this book, I discovered that bones have played an essential role in the history of mankind. They were practical, providing the material for tools. They were powerful, enabling people to foretell the future and ward off evil. They were decorative, fashioned into beautiful objects and jewelry. They were a source of entertainment used to make music and to play games. Bones and their symbolism pepper our language and literature. We still rely on bones in many ways in the modern world; they are in our bone china, in bone-meal fertilizer, and in many other products. Bones sustain man on many levels, and you will find their history and folklore on these pages.

I hope this book helps you rediscover bones and, most important, brings them back into your kitchen.