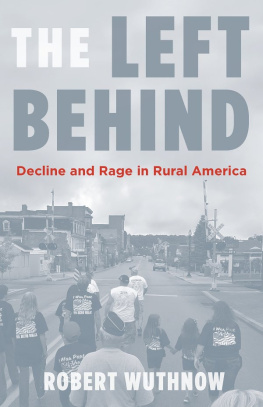

IN THE BLOOD

IN THE BLOOD

UNDERSTANDING AMERICAS

FARM FAMILIES

ROBERT WUTHNOW

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright 2015 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press,

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press,

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

Jacket photograph: Wind Turbines, Stacey Evans

All Rights Reserved

ISBN 978-0-691-16709-1

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Adobe Garamond Pro, Ristretto Slab Pro, and Ultra

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

CONTENTS

IN THE BLOOD

INTRODUCTION

Here in corn and soybean country the land stretches endlessly to meet the sky in all directions. Vast acreages of grain spread across gentle rises and shallow valleys. A row of tall electrical poles leads off the highway down a sanded country road toward a farmstead surrounded by trees. Corn ripens on one side and cattle graze on the other. Pungent goldenrod lining the fencerows scents the warm late summer air.

A left turn into the driveway reveals a modest two-story, hip-roof house cased in white aluminum siding. A thick evergreen shelterbelt protects the house on the north. Thinly spaced elms to the south permit ample sunlight during the winter. Near the back of the house a path to the swing set looks well used.

Farther along the driveway a double garage stands near a faded red barn and behind it a large metal machine shed. The machine shed is noticeably newer than the barn. Toward the end of the driveway a giant self-propelled spraying rig with upright folding booms flanks an outlying clutter of half-rusted implements from earlier days.

Neil and Arlene Jorgensen have been farming in this part of the country all their lives. They are fifth-generation farmers. Mr. Jorgensens parents, Clay and Mary, live a mile to the east and a quarter mile south. Clays greatgrandfather purchased the familys first quarter section here in the early 1880s. Clays grandfather built the house and barn where Clay and Mary live. Im still sleeping in the same bedroom I was born in, Clay says.

Families like the Jorgensens are the backbone of Americas rural economy. Many of these families have farmed in the same location for generations. In some areas they coax the nations corn and soybeans toward harvest, in other places they nurture its wheat, and in still others they tend its cotton. Their daily labor supplies the milk we drink and the fruits and vegetables we eat.

Family relations are integral to the Jorgensens farming activities. Neil and Clay farm in partnership. The two generations draw income from the same crops. Although Clay is old enough to have retired, he stays active running errands, helping feed the cows, manning one of the tractors during planting, and driving the truck during harvest. Neil does the heavy field-work and handles most of the management decisions. Hardly a day passes that the two do not spend time working together.

The Jorgensen women are as actively involved in farming as their husbands. Arlene has a job in town but does most of the farm bookkeeping. She and Neil decide together on major purchases, such as land and equipment. Mary looks after the grandchildren. Im the go-getter, she says, explaining that she runs errands, drives a tractor, and brings meals to the field during harvest. Neil eats at his parents house about as often as at his own.

Both couples are proud to be doing what their ancestors did. They consider it fortunate to be living near each other and working together. The physical labor is not as exhausting as it used to be. The tractors are bigger and better. Information technology has dramatically changed the way farming is done. The Jorgensens no longer raise hogs. Corn and soybean prices have been good the last few years.

The Jorgensens are also facing challenges. When Neil was growing up, it seemed natural that he would farm. He started helping with the chores in grade school and was driving the tractor by the time he was in junior high. I guess Ive got farming in my blood, he says. He hopes one of the children will follow in his footsteps but is unsure if that will happen. It has been harder to pass his knowledge on to his sons and daughters and to save enough to get them started. Machinery is almost prohibitively expensive. The new combine he purchased three years ago cost a quarter of a million dollars.

Relationships with the neighbors have been changing too. Clay remembers when neighbors shared machinery and got together to visit on Sunday afternoons. Now that he is almost retired, he meets a couple of other farmers his age for coffee early on weekday mornings. Neil is too busy. Besides that, there are hardly any farmers nearby. Only the ones with large tracts of land are left. Neil worries about being squeezed out before he is old enough to retire. The competition is fierce.

Then there are the challenges of keeping up with new technology. The high cost of machinery necessitates careful budgeting. Seed is now genetically engineered and costs ten times what it did a decade ago. New fungicides and pesticides come with confusing instructions. Too much at the wrong time will stunt the grain. Information technology makes it easier to stay current of new developments but also makes it important to keep up with market fluctuations.

A century ago approximately six million Americans farmed. That number has declined dramatically. According to the US Census Bureau fewer than 750,000 employed Americans list their principal occupation as farmer, meaning that they earn their primary living from farming land they own or rent. If people who describe themselves as farm managers are included, the

Although farmers are a small fraction of the US labor force, farming continues to be a topic of interest and importance to the nonfarming public. One reason is that nearly everyone interacts indirectly with farming three times a dayat breakfast, lunch, and dinner. The food supply depends on farming. We expect food to be there when we want it, and we expect it to be healthy and reasonably priced.

A second reason is that American history is rooted in farming. It is hard to understand Americas past without considering the central role of farming to leaders such as Thomas Jefferson and Andrew Jackson and among the millions of pioneers who settled the land. Many Americans who now live in cities and suburbs hale from farm families.

The cultural legacy of farming generates continuing interest in understanding the experiences of people who live close to the land. A person interested in literature does not have to look far to find accounts by writers who have left the city, returned to the family farm or purchased a small parcel, and described their experiences raising animals and rediscovering the serenity and challenges of rural life.

A third source of interest stems from the fact that rural America is vitally important to the nations public policy. What farmers do with the land they farm has important implications for environmental and energy policies. How agriculture is affected is an important consideration in international trade negotiations. It is a frequently contested issue in policy discussions about food stamps, school lunch programs, and public health.

Farming is also of interest and importance in academic discussions about the nature of society. Theories of society that emerged toward the end of the nineteenth century emphasized the large-scale shift from agrarian-based to industrial-based economies. With farm life declining, long-held traditions and values were assumed to be diminishing as well. Scholars expected the close-knit relationships that characterized farming communities to be replaced by something better suited to urban life. Gender relationships would probably change. Even religious beliefs and practices might change.

Next page