Packer - Into Africa

Here you can read online Packer - Into Africa full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: Chicago, Africa, East, year: 1994, publisher: University Of Chicago Press, genre: Home and family. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Into Africa

- Author:

- Publisher:University Of Chicago Press

- Genre:

- Year:1994

- City:Chicago, Africa, East

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Into Africa: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Into Africa" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Packer: author's other books

Who wrote Into Africa? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Into Africa — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Into Africa" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

INTO AFRICA

With a New Postscript

Craig Packer

The University of Chicago Press

Chicago and London

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

1994, 1996 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. Published 1994

Printed in the United States of America

13 12 11 10 09 08 07 06 05 04 3 4 5

ISBN: 978-0-226-05599-2 (e-book)

ISBN: 0-226-64430-8

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Packer, Craig.

Into Africa / Craig Packer.

p. cm.

1. Packer, CraigJourneysAfrica, East. 2. EthologistsUnited StatesDiaries. 3. MammalsBehaviorResearchAfrica, East. 4. Africa, EastDescription and travel. I. Title.

QL31.P15A3 1996

599.05109676dc20

[B] 94-17889

CIP

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

Part I

LION EYES

MINNEAPOLIS / SATURDAY, 26 OCTOBER 1991

In spite of myself, my heart is racing toward Africa. Behind my closed eyes I sense, for one fleeting moment, an impending warmth, glimpse a flash of brilliant colors. Green is mixed with gold, blue with black. I recall a world where time means more than the dull tick of anxiety, where individual existence is all but lost in the vast rhythms of life.

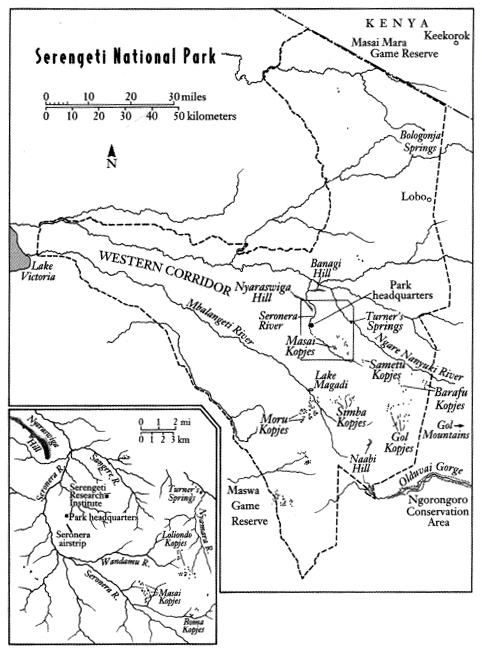

But the vision quickly passes and I am gripped by chronic exhaustion. Slumped in my seat, I am flying from Minneapolis to Nairobi via London and Rome. My ultimate destination is Tanzania, where I study the lions of the Serengeti and Ngorongoro Crater and collaborate with Jane Goodall on the baboons and chimpanzees of Gombe National Park. I am engrossed by the social evolution of these animals: Why do some individuals live longer than others? Why do some raise more babies than the rest? Why do they live in groups? Why do they cooperate?

Cooperation in nature is rare, but lions, baboons, and chimpanzees are among the most cooperative of all mammals. Lions are the most social of cats; chimps and baboons live in the most complex of primate societies. These are animals worthy of study in their own right, but their worlds also reveal something about ourselves. Human society may be the product of our own making, but I suspect we are motivated by many of the same desires and fears felt by any other animal.

This trip may sound exciting to most of the other passengers on board, but I am reluctant to leave the world of constant electricity and instant information. It is my sixteenth trip to Africa, and I have already traveled too much this year. I am a professor at the University of Minnesota. Most of my research has been done in collaboration with my wife, Anne, also a Minnesota professor. For over a decade, we spent half of each year in the Serengeti, but we can no longer shift our lives at the drop of a hat. Anne is staying behind in Minneapolis this time to catch up on her writing, and our kids need a chance to settle into school. They have already spent too much of their lives on the road.

So for the past few years we have spent as much time as possible investigating these animals on paper. The lions and baboons have been studied continuously for twenty-five years, and Jane has studied the chimps for thirty. Each of these long-term chronicles is equivalent to almost a century of human history. We have just finished cleaning up and collating the abstract biographies of all the lions, and the answers to many of our most important questions are now sitting in our computers, waiting to be revealed.

Now it is time to switch perspectives, to confront the living, breathing beasts. I would love to take a break from it all, but we are trying to solve fundamental problems about how cooperation can arise in an ocean of self-interest. The historical records must be kept unbroken, and so I return each year to the other side of the earth. The excitement of scientific discovery is still intense. Those few crystalline hours are worth any kind of hardship, any amount of hard work.

LONDON / SUNDAY, 27 OCTOBER

I arrive at 6:00 AM and wait for the others to appear at Heathrow Terminal Two. Combating cramp and fatigue, I move about as much as I can, wandering slowly between the garishly lit newsstands and the orange signs at the Alitalia desk. By mid-morning, the plastic highlights have all faded against the grey walls, grey floors, grey sky.

The hallway has gradually filled, and the terminal looks like an ad for the United Nations, with people from all over the world waiting peacefully for their flights. Hostile nations on neutral ground: Arabs, Asians, Africans, Europeans. But this taxonomy is too crude. We live on a tribal planet where local identities mean much more than race. I cant distinguish Norwegian from Dane, Syrian from Lebanese, Tahitian from Fijian; I cant read the lines of regional hostilities on each face.

In the waiting area, an Asian woman (Is she Indian? Bengali? Pakistani?) keeps a close watch on her little boy. He is not quite two years old. He wanders a few yards from his mother and finds something on the floora discarded baggage label. Waving it about in triumph, he charges around the alcove, victorious in his first battle of the day. He starts to lose all self-restraint, runs into strangers, whirls on the floor. Mother quickly rises and brings him back into line. She tries to instill a little discipline, then distracts him with a toy. The child converts the toy into a gun. Dozens of fellow passengers are mortally wounded. Mother tries to ignore the carnage. Shot for a fifth time, I finally fire back with my index finger. Tomorrows warrior doesnt know whether to laugh or cry. Confused, he suddenly wilts and hides behind his mothers sari.

At 10:00 AM, Karen McComb arrives from Cambridge to swap video equipment and say hello. She has recently finished a two-year stint with the lions in the Serengeti and will spend the next few months in front of a television monitor in her college office, watching tape-recorded lions and reliving her years in the tropics.

Over the next half hour my three traveling companions appear one by one from different parts of Britain: Christine from Oxford, Sarah from Aberdeen, and Pamela from Belfast.

Christine is an ecological parasitologist who will be investigating the intestinal outpourings of our study animals. Christine came from Germany to Oxford, where Anne and I spent our sabbaticals last year. Our field associates have already sent her dozens of fecal samples from the Serengeti and Gombe. By looking for worms and eggs in each specimen, she has already discovered that some animals are more heavily infected than others. She cant yet tell why, and her research will succeed only if she can detect a clear pattern in her data. Do animals that eat together share the same worms? Are they healthier in drier habitats? Can monkeys be infected by humans? Christine will accompany me throughout this trip, then park herself on a lab bench for the next two years. She has a mere seven weeks to see the animals behind the samples, seven tightly scheduled weeks in which nothing can go wrong.

I have met Pam and Sarah only once before, when they interviewed for a three-year job as field assistant on the lion project. They had recently graduated from Edinburgh University and had conducted research in Scotland and Siberia. Anne and I had planned to hire only one person, but we liked both Pam and Sarah so much that we couldnt choose between them. It also seemed smarter to send them out as a team so that they could look after each other when confronted by equipment failures or by rapacious African officials. But we cant provide them with two decent salaries, so they will be dividing a single modest paycheck from our latest grant.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Into Africa»

Look at similar books to Into Africa. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Into Africa and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.