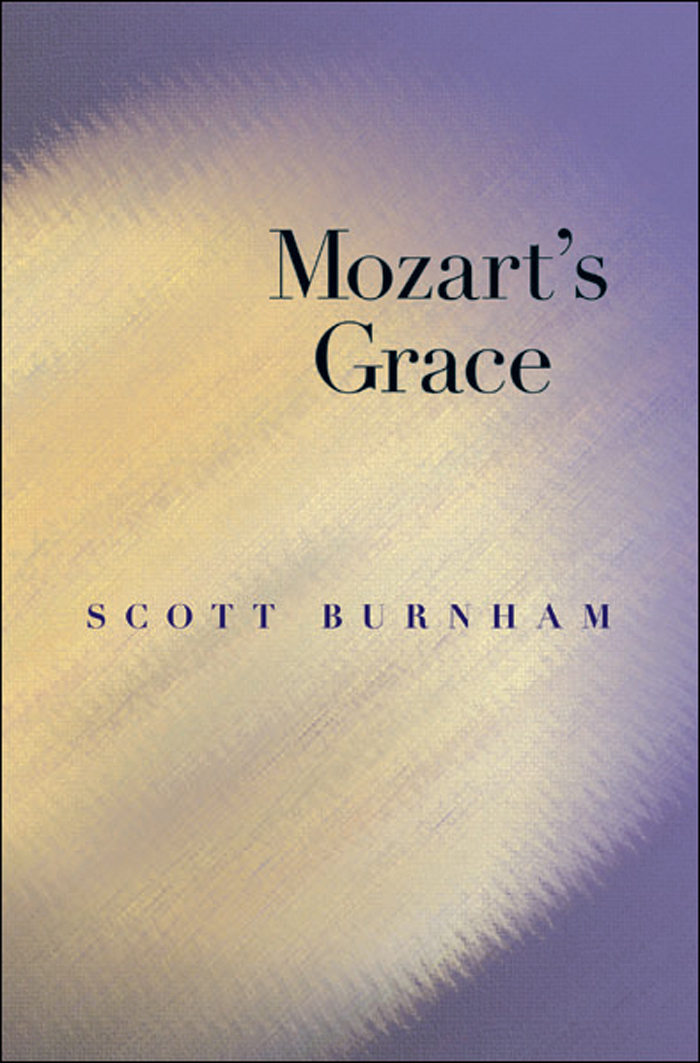

Mozarts Grace

Mozarts Grace

SCOTT BURNHAM

Princeton university Press

Princeton and Oxford

Copyright 2013 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press,

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press,

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Burnham, Scott G.

Mozarts grace / Scott Burnham.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-691-00910-0 (hardcover)

1. Mozart, Wolfgang Amadeus, 17561791Criticism and interpretation. I. Title.

ML410.M9B974 2013

780.92dc23 2012030026

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Sabon LT Std

Book designed by Marcella Engel Roberts

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

For my favorite Mozart-loving angels, here and elsewhere:

Evalyn Foote Burnham

Luisa Heyl Foote

CONTENTS

_____________

_____________

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

In some sense this project began about thirty years ago, in the company of my old friend Jeff West, as we marveled together at various passages in Mozarts music. One that stood out in particular for us was the stunning return to the theme in the middle of the Adagio from the String Quintet in D Major, K. 593. Some fifteen years later, I revisited that passage in a paper called Rehearing Mozart, delivered in honor of Edward T. Cones eightieth birthday, in which I pondered how it is that we can rehear our favorite musics over and over again with enhanced enjoyment. Next, in November of 2001, I participated in Music and the Aesthetics of Modernity, a conference in honor of Reinhold Brinkmann at Harvard University, where I presented On the Beautiful in Mozart, a paper that became the prototype for this book.

On that occasion I was the grateful recipient of invaluable feedback and encouragement from Karol Berger and Anthony Newcomb, who organized the conference and edited the proceedings in a Festschrift for Reinhold (Music and the Aesthetics of Modernity, Harvard University Press, 2005), and also from Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht, Robert Levin, David Lewin, Lewis Lockwood, Charles Rosen, James Webster, and especially Reinhold Brinkmann himself, who upon publication of the essays, and in the midst of a debilitating illness, sent me a note of thanks with faltering handwriting but unwavering generosity and warmth of spirit.

Since then, I have been fortunate enough to read several additional papers related to this project for colleagues at a variety of institutions, including Case Western Reserve University, Cornell University, Florida State University, Indiana University, Ohio State University, Peabody Conservatory, Pennsylvania State University, Rider University, Stanford University, the State University of New York at Stony Brook, Swarthmore College, and the universities of Alabama, Iowa, Michigan, Oklahoma, and Oslo. On these many occasions I was the beneficiary of the expertise and enthusiasm of friends and colleagues too plentiful to enumerate here. But I would like to single out a few special individuals: Joseph Kerman, who shared with me an unpublished paper on K. 453; Leo Treitler, whose genial public response to my talk Supernatural Mozart remains a highlight of my academic career; and Charles Rosen, whose discussions and performances of Mozart (both recorded and impromptu) have taught me much over the years.

I also benefited enormously from presenting various parts of this project at Princeton University: to Eric Clarke, Jonathan Cross, and Laurence Dreyfus, visiting members of the Oxford-Princeton Music Analysis Study Group; to the amazing community of spirits in our Society of Fellows in the Liberal Arts, including my friends Mary Harper, Carol Rigolot, and Susan Stewart; to Kofi Agawu and Joseph Straus, friends and fellow members of the Princeton Theory Group; and to receptive and engaged groups of students and colleagues in the Music Department, as part of our Music Theory Group and our Work in Progress Series.

I am grateful to several anonymous readers for Princeton University Press, who challenged and encouraged me. Getting detailed reactions from gifted musicians and thinkers is always a stimulating experience, doubly so when the music in question is that of Mozart. Karol Berger and Mary Hunter also read the first full draft of my manuscript, and both revealed a fine sense of what I was trying to achieve, even amid the imperfections of my initial attempt to do so. I am also grateful for the example they have provided in their own inspiring work on Mozarts music. And if it were only possible, I would pick up the phone right now and tell Wendy Allanbrook how crucially important her magical book Rhythmic Gesture in Mozart (University of Chicago Press, 1983) has been to me and to everyone else in the field.

A number of people at Princeton University Press have made this book better and kept it on track. These include Fred Appel, whose infinite patience encompassed being able to hear for years that the book was just around the corner; Jodi Beder, musician and copy editor, who applied a generously exacting ear to the voice leading of my prose; Karen Carter, who oversaw the entire process of publication with humane ministrations; and Sarah David, who cheerfully assisted with a wide range of details surrounding production.

Seth Cluett, Laura Hedden, and Sanna Pederson each helped me mull over variants of the books title. Somangshu Mukherji drew up the music examples seemingly as effortlessly as Mozart composed them. And the extraordinary Jim Clark offered me invaluable help and support at a ticklish stage of the project.

Sometimes I simply cant believe how lucky I am in my colleagues, my friends, and my family. At home I am continually blessed with the rejuvenating presence of Emmett, Sophia, and Georgia, musical spirits all. But it is Dawna Lemaire to whom I am most profoundly indebted: Dawna, who was playing Mozarts Rondo in A Minor around the time I was writing the bulk of this book; Dawna, who always listens carefully to my takes on various musical passages and never fails to add an elevating thought that is both musically and humanly insightful; and Dawna, whom I do not deserve, never thank enough, and hope someday to live up to.

Mozarts Grace would have been impossible to write without sabbatical leaves supported by the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation and the National Humanities Center. The music examples in Mozarts Grace were drawn up with the kind permission of the Neue Mozart Ausgabe, on which we relied for everything except occasional piano reductions of instrumental textures.

Mozarts Grace

INVITATION

Anticipatory Pronouncements...

Whoever has discovered Mozart even to a small degree and then tries to speak about him falls quickly into what seems rapturous stammering. Bach, then, is always on the job, but when the agents of divinity go off duty, they turn to Mozart, as to the sounds of familial love and joy.

Others, without making direct reference to the divine, have heard Mozarts music as emanating from a heightened prospect. Schubert confided to his diary that Mozart offers comforting perceptions of a brighter and better life; Wagner spoke of Mozart as musics genius of light and love.