Praise for The Unseen

What [Balestrini] narrates is not a fairy tale, but a terrifying experience. Not just his own, but also that of a lost generation who thought possible another world beside the world, who dreamt of workers power, of autonomy, who revolted against everything, school, family, clergy, political parties, historical compromise, State, police, boredom... The Unseen is, perhaps, the first true novel of the European Left. Libration

Balestrini offers a very lucid document, which is both the memory and the assessment of a disoriented generation. The Left now has its novel. Lvnement du jeudi

The Unseen isnt documentary writing, but it tells us far more than any documentary about a troubled phase in our history; how it was experienced, and most of all how it was lived in the imagination. Corriere della Sera

We should be grateful to Nanni Balestrini for having engaged his writing with this cruel sentimental education of a young man living in the seventies. Rossana Rossanda, il manifesto

The political passion of the rebel Balestrini is equalled by his literary vocation ... the finale is not unworthy of Bontempelli or Calvino. Il Giornale

A work of high literary quality. Among many novels and elegantly crafted pieces of fiction ... The Unseen has the courage to face an incandescent matter of reality, rich in implications that involve not only the literati but also a wider public. LUnit

Not just a beautiful novel ... it is the story of part of a generation in our country, who dreamed a different future and believed in it, believed in the possibility of making it real. Linus

NANNI BALESTRINI was born in Milan in 1935 and was a member of the influential avant-garde Gruppo 63, along with Umberto Eco and Eduardo Sanguineti. He is the author of numerous volumes of poetry, including Blackout and Ipocalisse , and novels such as Tristano , Vogliamo Tutto , and La Violenza Illustrata .

During the notorious mass arrests of writers and activists associated with Autonomy, which began in 1979, Balestrini was charged with membership of an armed organization and with subversive association. He went underground to avoid arrest and fled to France. As in so many other cases, no evidence was provided and he was acquitted of all the charges.

He currently lives in Rome, where he runs the monthly magazine of cultural intervention Alfabeta2 with Umberto Eco and others.

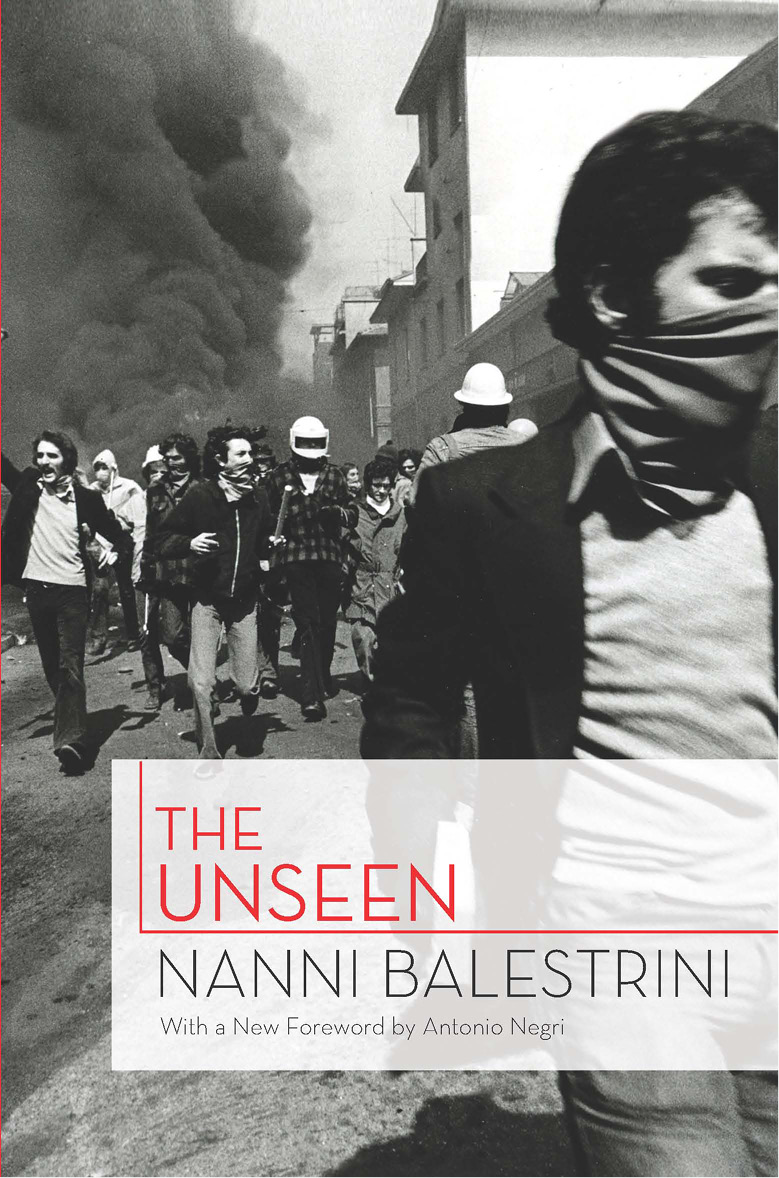

The Unseen

Nanni Balestrini

TRANSLATED BY LIZ HERON

WITH A FOREWORD BY ANTONIO NEGRI

First published in English by Verso 1989

This updated paperback edition published by Verso 2011

This updated edition Nanni Balestrini and Derive Approdi, Rome 2005

Translation Liz Heron 1989, 2011

Foreword Antonio Negri 2011

First published as Gli Invisibili

Bompiani, Milan 1987

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

www.versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

Epub ISBN-13: 978-1-84467-837-2

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

Typeset in Janson MT by Hewer UK Ltd, Edinburgh

Printed in the US by Maple Vail

for Sergio

Contents

Foreword

Nanni Balestrinis book, now republished here, tells of unseen actors in the class struggle between the 1970s and 80s, particularly in northern Italy, and inside the jails of the Realm. These subjects are invisible because they are elusive, mutating beings in the act of metamorphosis. But what can we say about them today (and also about this novel) if not that rather than being an old, outdated story this is now very much of the present moment, one caught sight of at that time and followed in the course of its unfolding? The republication of The Unseen therefore has the advantage today of telling us about proletarian subjects whose class nature has finally been revealed: the unseen individual of yesterday is the proletarian of today, the immaterial worker, the cognitive precariat, the new figure of the worker as social labour power in the movements of the multitude. Those poor wretches did it, they managed to get through a revolution in the composition of labour and a ferocious political repression and to struggle on from the factories to society and (still productive) from society to the jail (still fighting back). And now where will they go? The elite of the working-class movement who betrayed and dragged the unseen into prison now look around, fearful and unable to build a politics, afraid of losing out if they do not resume contact with that age-old movement of transformation; but that elite will never win! Indeed, regardless of this betrayal by the working-class movement (which has been so serious, especially in Italy), the unseen have gone forward. In the 80s, they were organizing prison revolts and the first autonomous social centres in the cities; in the 90s they organized the Panther movement; in the late 90s they turned into Zapatistas and tute bianche , the anti-globalization movement and everything else that has happened and will happen.

It is interesting to note that each one of these movements always sought to give itself ambiguous, hard-to-pin-down names that could have been white but also dark in the shadow that the white produced, that could have been soft like the tread of a feline, that could moreover position itself as tireless resistance precisely in the name of the singular ambiguity of its disobedient behaviour. Since the 70s, these movements have all understood that starting all over again doesnt mean turning back but rather expanding, reaching into new spaces and new times, being coordinated and coordinating, seeking confrontation in the measure of consensus and consensus in the measure of confrontation. The fact is that, in contrast to the parties and the survivors from the ancien rgime , the unseen place themselves in the here and now. Balestrinis unseen, right from the early 80s, were beginning to give shape to a multitudinous, singular, transversal subject that wanted never to be reduced to a mass but wanted in every case to be a whole. And even when ideological reminiscences drew them inside names and terminologies that sounded out of date, at that same moment this subject was able to invent itself anew. Think of the scene where the prisoners in the Trani revolt are locked up in their cells after the bloodbath and shed with their flaming torches a light that illuminates the night of every proletarian prison of the decade. This is the language of the multitude. But if it were no more than this, this reality in its biting descriptions, Balestrinis book might only be a piece of historical or sociological documentation. What is great about this novel is that the unseen individual becomes a literary subject. Larvatus prodeo the proletarian advances masked by his invisibility. And with this transformation in those years of the 70s which the bosses and their servants within the working-class movement failed sufficiently to curse he represents the invisible yet powerful transformation from material work to immaterial work, from revolt against the boss to revolt against the patriarchy, along with the metamorphosis of bodies brought about within this movement, and the imagination that this new historical condition (social and political to be precise) brings to speech.

Next page