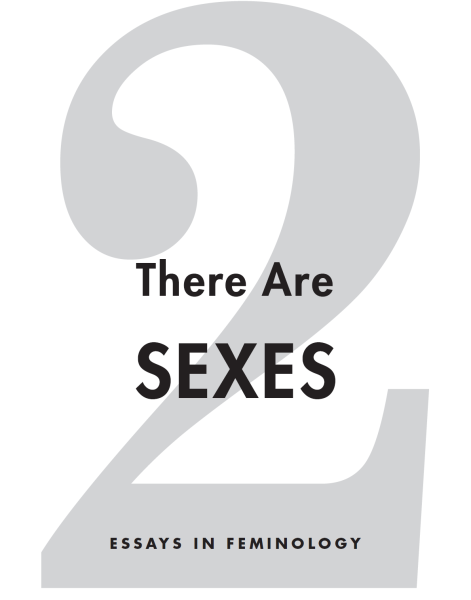

There Are Two Sexes

FOREWORD BY JEAN - JOSEPH GOUX

antoinette fouque

TRANSLATED BY DAVID MACEY AND CATHERINE PORTER

EDITED BY SYLVINA BOISSONNAS

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS New York

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS

PUBLISHERS SINCE 1893

NEW YORK CHICHESTER, WEST SUSSEX

cup.columbia.edu

Il y a deux sexes, copyright 1995, expanded edition copyright 2004, Gallimard

Copyright Editions Des femmes:

chapter 23, Gravida, in Gravidanza (2007)

chapter 24, What Is a Woman, in Gnration MLF (2008)

chapter 25, Gestation for Another, Paradigm of the Gift, in Gnsique (2012)

foreword by Jean-Joseph Goux (2013)

Copyright 2015 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-53838-1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Fouque, Antoinette.

[Il y a deux sexes. English]

There are two sexes: essays in feminology / Antoinette Fouque;

foreword by Jean-Joseph Goux; translated by David Macey and Catherine Porter; edited by

Sylvina Boissonnas.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index

ISBN 978-0-231-16986-8 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-231-53838-1 (e-book)

1. Women. 2. Feminism. 3. Sex role. I. Title.

HQ1208.F6813 2015

305.4dc23

2014026340

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

BOOK & COVER DESIGN: CHANG JAE LEE

References to websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor Columbia University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

For Vincente and Ezekiel

Contents

Antoinette Fouques work should have been introduced to English-language readers much earlier. It is highly regrettable that the vigorous American debate over French feminism, or, more broadly, over the question of gender, has not benefited from Fouques original, coherent, and persistent thinking. For several decades now, American feminists, or, to take a wider view, womens studies programs, have analyzed, debated, supported, or contested, after Simone de Beauvoirs contributions, those of Luce Irigaray, Julia Kristeva, Hlne Cixous, and Monique Wittig. Although it is fair to say that Fouque, through her actions, speeches, and writings, has been the chief inspirational force behind the most original and most combative dimensions of the French womens liberation movement, her name appears very rarely in the Anglophone context. There is an anomaly here that the publication of this book by Columbia University Press will, happily, begin to rectify.

From 1968 on, with the creation of the group known as Psychanalyse et Politique (Psychoanalysis and Politics) and the beginning of the Mouvement de Libration des Femmes (Womens Liberation Movement, or MLF), Antoinette Fouques actions and theoretical positions have given a decisive impetus to French feminism. Her orientations have had a determining influence, in various forms, on all women whose thought has been burgeoning since the earliest manifestations of this group and this movement.

In this connection several points stand out as marking the originality of Fouques theoretical and practical positionspositions that were to have widespread repercussions on what later came to be called French feminism.

Fouques specific ideas about womens liberation can also be read as a critique of Simone de Beauvoirs feminism. With that form of feminism, in Fouques view, what was won in terms of emancipation was accompanied by an onerous renunciation. The woman who had to ignore or abandon all ambitions in order to devote herself to procreation (the traditional situation under the patriarchal regime) was succeeded by a woman who had to sacrifice her desire to procreate in order to satisfy her ambitions. Thus women emerged from the age-old maternal slaveryand this was certainly a first major step toward their liberationbut at the price of repressing the desire for a child. In Fouques view, what was required was not to pretend to be unaware of the strength of that desire, but rather to make a place for it in womens liberation. Beauvoirian feminism thus had to be surpassed by a new phase that would no longer be feminism in the limited sense, but a true liberation that would take into account the entire set of factors involved in womens full development, countering any notion that the difference between the sexes should be neutralized. In this sense, for Fouque, the feminist challenge remains internal to the patriarchal enclosure, as a position that seeks to obtain powers, roles, and functions for women that had previously been the monopoly of men, but to the detriment of womens own capacities, among which procreation is the most significant and the most inalienable. It is not true that a woman is a man like any other, as certain feminist slogans from the early days proclaimed. This is why Fouque can declare that she is not merely a feminista claim that may be surprising and subject to misunderstanding if it is not resituated in the context of the contemporary debates.

Antoinette Fouques work is aimed at a more complete liberation of women, beyond the limitations that the first feminism imposed. She locates herself within a postfeminism that requires not only political and institutional advances but also a theoretical and philosophical step forward. This step calls for a new understandingwithout regressing to earlier positionsof the female libido that is at work in the desire for a child, in gestation, in childbirth. The Freudian conception, accentuated by Lacan, of a single libido that is the same in men and in women and for which the phallus would be the master signifier ought to be succeeded by a conception that takes into account the libido proper to women. Alongside the phallic libido there is the other one, uterine and matricial: the libido creandi. Fouques relation to Freud stems from this fundamental position: she critiques the ideology of masculinity that prevails in Freud and Lacan, but she does not repeat the gesture of a certain feminism that simply liquidates psychoanalysis, for psychoanalysis still offers the only discourse there is on female sexuality. For Fouque, it is more a matter of amending and expanding psychoanalytic theory by challenging it with what is specific in female desire: above all, the desire to procreate. It is in relation to this partial and critical acceptance of Freudian psychoanalysis within the MLF that the well-known collective Psychanalyse et Politique (often called Psych et Po) was established, with the goal of exploring the connections between the unconscious and the political: the unconscious in the political, and also the powers deployed, the hierarchies created, within the unconscious.

This work of elucidation is accompanied by a reinterpretation of genitality, a libidinal phase that was recognized by Freud but that tends to be conflated with the phallic stage, owing to the supremacy attributed to the latter; in Lacans case it tends to be forgotten or even contested. Not only is it essential not to ignore the desire for a child specific to the libido creandi or reduce it to the phallic, but it is essential that gestation, pregnancy, the obscure metamorphoses that take place within womens bodies, all the organic work that has always seemed to go on at an infrasymbolic level, be brought into language and acknowledged at the symbolic level. Hence metaphoric fertility in cultural and artistic creation is also implied in men and women alike.