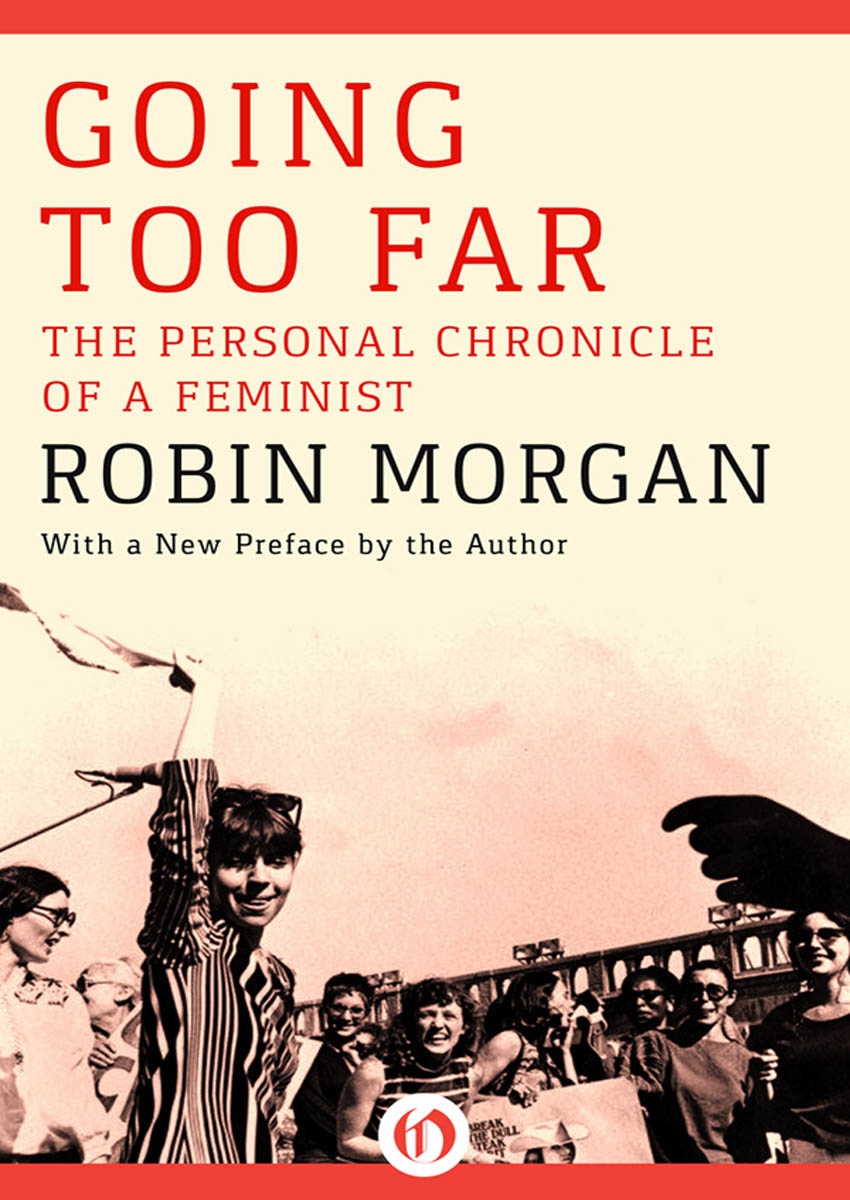

Going Too Far

The Personal Chronicle of a Feminist

Robin Morgan

WOMEN DISRUPT THE MISS AMERICA PAGEANT

The following piece is based on an article of mine which appeared in various New Left publications. I made no pretense at being an objective journalist (if such an animal ever existed); I had been one of the organizers of the demonstration, and so my article was a perfect example of what then was called proudly participatory journalism.

The 1968 womens demonstration against the Miss America Pageant in Atlantic City was the first major action of the current Womens Movement. It announced our existence to the world, and is often taken as the date of birth of this feminist wave (as differentiated from the nineteenth-century feminist suffrage struggle). If it was the birthdate, conception and gestation had been going on for a long time; years of meetings, consciousness-raising, thought, and plain old organizing had taken place before any of us set foot on the boardwalk.

It was out of that first group, New York Radical Women, that the idea to protest the pageant developed. Almost all of us had been active in the civil-rights movement, the student movement, or some other such wing of the New Left, but not one of us had ever organized a demonstration on her own before. I can still remember the feverish excitement I felt: dickering with the company that chartered buses, wangling a permit from the mayor of Atlantic City, sleeping about three hours a night for days preceding the demonstration, borrowing a bullhorn for our marshals to use. The acid taste of coffee from paper containers and of cigarettes from crumpled packs was in my mouth; my eyes were bloodshot and my glasses kept slipping down my nose; my feet hurt and my neck ached and my voice had gone hoarseand I was deliriously happy. Each work-meeting with the other organizers of the protest was an excitement fix: whether we were lettering posters or writing leaflets or deciding who would deal with which reporter requesting an interview, we were affirming our mutual feelings of outrage, hope, and readiness to conquer the world. We also all felt, well, grown up; we were doing this one for ourselves, not for our men, and we were consequently getting to do those things the men never let us do, like talking to the press or dealing with the mayors office. We fought a lot and laughed a lot and felt very extremely nervous.

Possibly the most enduring contribution of that protest was our decision to recognize only newswomen. There was much discussion about this, and we finally settled on refusing to speak to male reporters not because we were so nave as to think that women journalists would automatically give us more sympathetic coverage but rather because the stand made a political statement consistent with our beliefs. Furthermore, it would raise consciousness on the position of women in the mediaand maybe help more women get jobs there (as well, perhaps, as helping those who were already there out of the ghetto of the womens pages). It was a risky but wise decision which shocked many at first but which soon set a precedent for almost all of the Womens Movement. Today most networks, wire services, and major newspapers across the country know without being reminded that newswomen should be sent to cover feminist demonstrations and press conferences. And this has perceptibly helped to change the heretofore all-but-invisible status of women in media.

We also made certain Big Mistakes in our protest. Not so much the tactical ones: we had women doctors and nurses there, and women lawyers and stand-by emergency phone numbers and local turf to which we could strategically flee if the going got too ugly. Our mistakes were more in the area of consciousness about ourselves and other womenwho we really were and who we wanted to reach. For example, our leaflets and press statements didnt make the point strongly enough that we were not demonstrating against the pageant contestants (with whom, on the contrary, we expressed solidarity as women victimized by the male system). Too many of our guerrilla-theater actions seemed to ridicule the women participants of the pageant rather than the pageant itself. The spontaneous appearance of various posters sprouting slogans like Miss America Goes Down and certain revised song lyrics (such as Aint she sweet/making profit off her meat) didnt help matters much.

Still: we came, we saw, and if we didnt instantly conquer, we learned. And other women learned that we existed; the week before the demonstration there were about thirty women at the New York Radical Women meeting; the week after, there were approximately a hundred and fifty.

A year later, there was another demonstration in Atlantic City; I went as a reluctant old organizerto help those who were putting it together that year out of my experience from the previous year. I had given birth less than two months earlier and was breast-feeding the baby, who was clearly too young to hack an all-day and most-of-the-night demonstration. Thus my memories of the protest in 1969 tend to focus on my worrying that the child would accept my husbands bottle-feeding, and on my own keen discomfort with milk-full breastswhich I regularly emptied via a tiny breast pump I had brought along for that purpose, quitting the picket line every two hours or so to dash to the nearest ladies room and pump myself out. Such are the vicissitudes encountered by a feminist activist.

The protests have continued, becoming an annual event in themselves. Meanwhile, the pageant gets sillier and draws less of an audience each year. The time will come when feminists automatically gearing themselves up for the Miss America protest will have to remind themselves that there is no longer anything there about which to protest.

N O MATTER how empathetic you are to anothers oppression, you only become truly committed to radical change when you realize your own oppressionit has to reach you on a gut level. This is what has been happening to American women, both in and out of the New Left.

Having functioned underground for a few years now, the Womens Liberation Movement surfaced with its first major militant demonstration on September 7, 1968, in Atlantic City, at the Miss America Pageant. Women came from as far away as Canada, Florida, and Michigan, as well as from all over the Eastern Seaboard. The pageant was chosen as a target for a number of reasons: it is, of course, patently degrading to women (in propagating the Mindless Sex Object Image); it has always been a lily-white, racist contest (there has never been a black finalist); the winner tours Vietnam, entertaining the troops as a Murder Mascot; the whole gimmick of the million-dollar Pageant Corporation is one commercial shill-game to sell the sponsors products. Where else could one find such a perfect combination of American valuesracism, militarism, capitalismall packaged in one ideal symbol, a woman. This was, of course, the basic reason why the protesters disrupted the pageantthe contestants epitomize the role all women are forced to play in this society, one way or the other: apolitical, unoffending, passive, delicate (but drudgery-delighted) things.

About two hundred women descended on this tacky town and staged an all-day demonstration on the boardwalk in front of Convention Hall (where the pageant was taking place), singing, chanting, and performing guerrilla theater nonstop throughout the day. The crowning of a live sheep as Miss America was relevant to where this society is at; the crowning of Miss Illinois as the real Miss America, her smile still blood-flecked from Mayor Daleys kiss, was also relevant. The demonstrators mock-auctioned off a dummy of Miss America and flung dishcloths, steno pads, girdles, and bras into a Freedom Trash Can. (This last was translated by the male-controlled media into the totally invented act of bra-burning, a nonevent upon which they have fixated constantly ever since, in order to avoid presenting the real reasons for the growing discontent of women.)