foreword

My name is Ed Stafford and Im alive.

Therefore, like you, Im a survivor. I dont

mean to be facetious but there are

many times in my life when I could

have died.

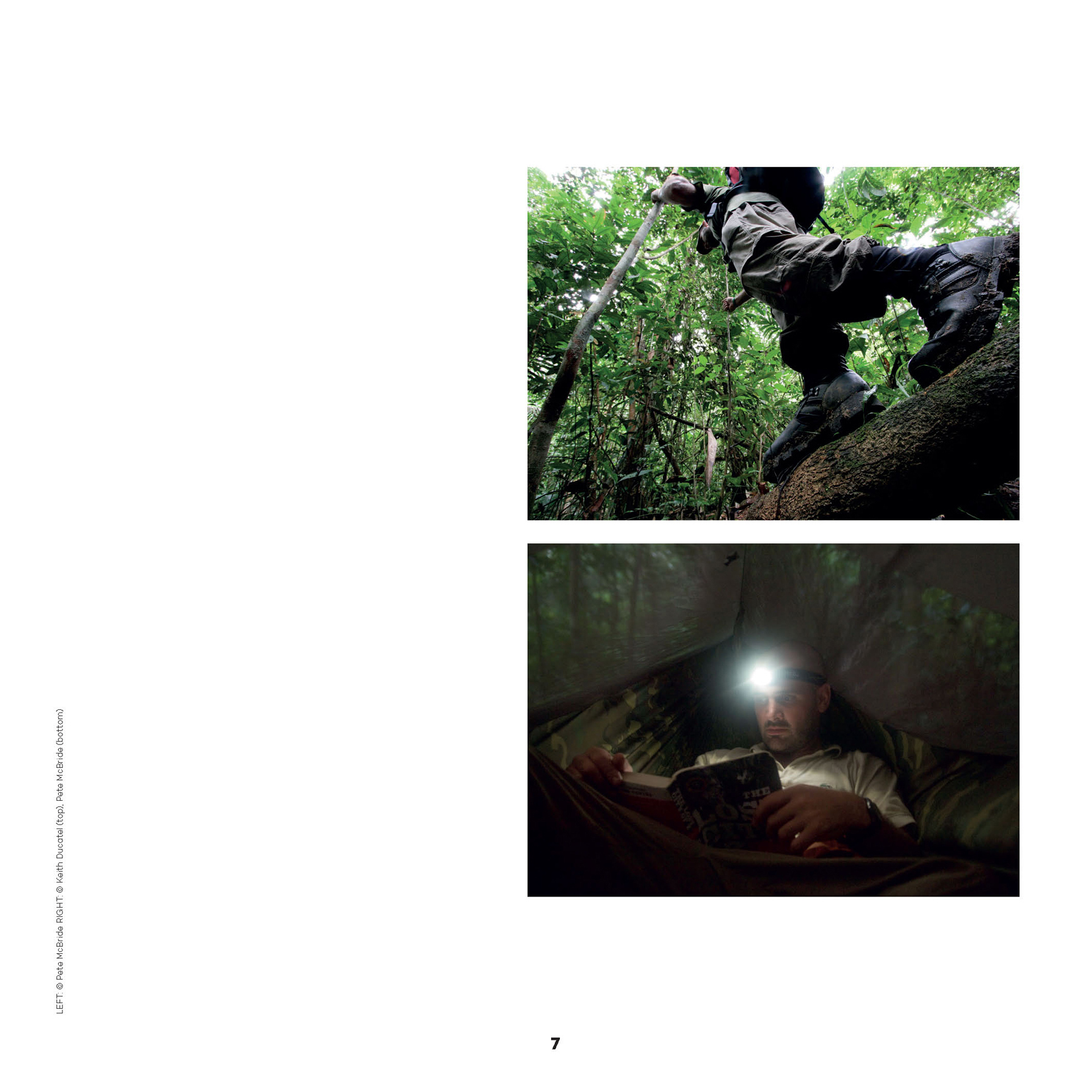

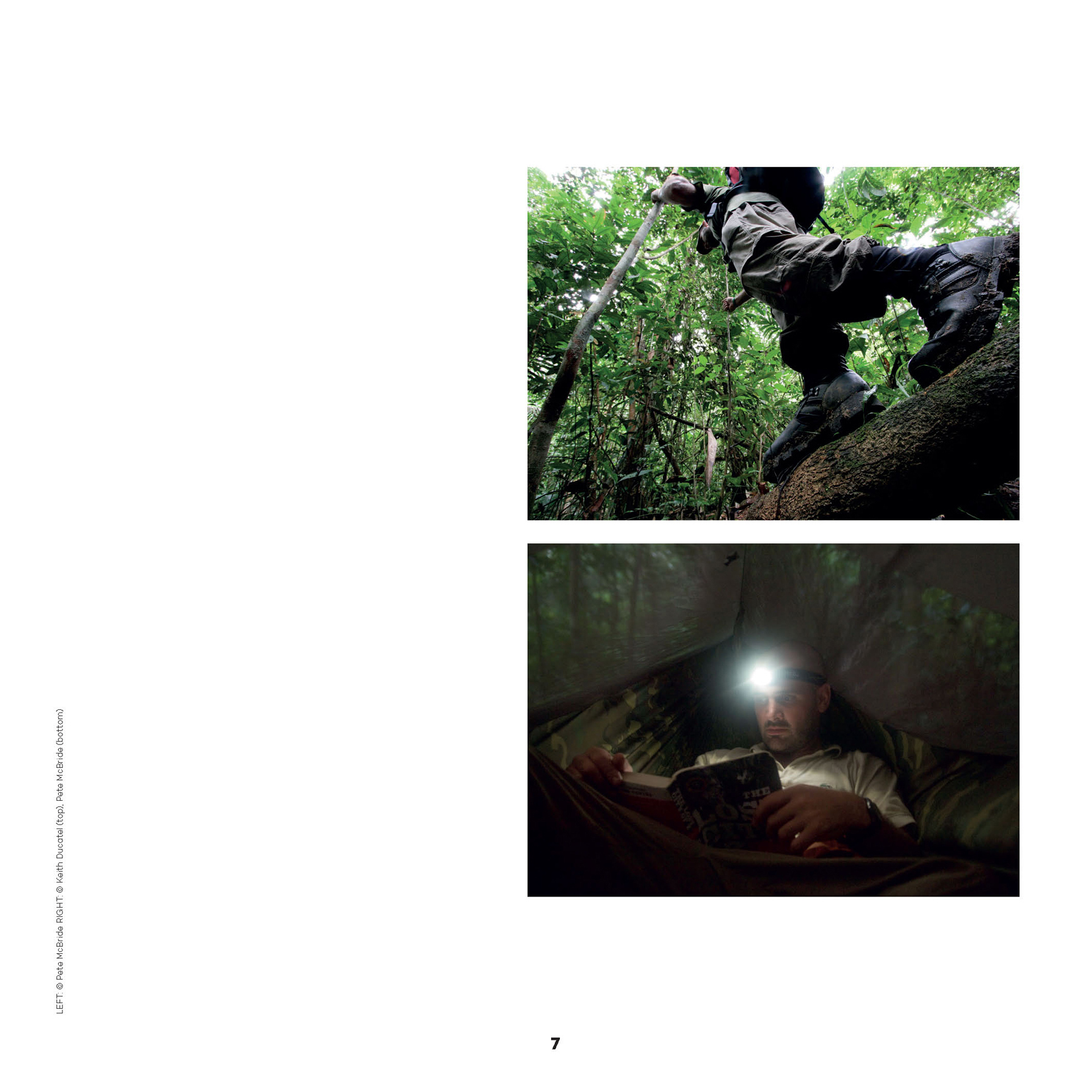

In 2010 I became the first human to walk

the length of the Amazon from source

to sea. Four thousand miles, 860 days,

seven pairs of boots, and one Guinness

World Record. Before I set out (and all

along the route) everyone told me I was

going to die. On the way I was held up at

arrow point by Asheninka Indians, at gun

point by drugs traffickers, electrocuted

by an electric eel, and arrested for

suspected murder by Shipebo people.

I suppose the naysayers were right

I could have died. But I didnt.

Fast forward two years and I chose to

strand myself naked (and with nothing

to help me survive) on an uninhabited

island in the Pacific for 60 days. With

no-one to talk to, I built an existence

from scratch. Eating raw snails and

coconuts eventually progressed to

managing to light a fire and opening up

new possibilities such as roasting feral

goats legs. I built myself a home in the

trees and, after two months on my own,

even plumbed it with guttering and a

rainwater collection tank made from

washed-up debris. I proved to myself

that I could survive with nothing but

two hands and half a brain.

Why do I take on such trips? Of course, I thrive

off the adrenaline. But its more than that. I was

adopted as a baby, and that lies at the heart

of it: I am genuinely grateful to have even been

born. It could easily have been very different.

I was lucky and I was given my crack at living

a full life. We all are, I suppose. I have no

intention of wasting it.

But things dont always go to plan. On one

occasion in the Amazon, when I was over two

weeks walk from any human settlement, my

GPS died. I wasnt sure if it was the unit or

whether there had been a nuclear war as all the

satellites had gone down. It didnt really matter.

I had to make do with a 1:4,000,000 tourist

map of South America and a cheap compass.

There was such a high margin for error in my

calculations each day that they were a joke.

If it hadnt been life-threatening, it would have

been hilarious. The advice in this book on how

to survive in the wild without GPS (pages

) might just have come in handy. Hindsight

is a beautiful thing, as they say.

Sometimes, prevention is better than cure.

I was once stranded naked in Rwanda without

any form of sun protection, so I covered my

head and shoulders in hippo faeces. It

stopped me from burning and my girlfriend

even commented on how smooth my skin

was when I got home. Bonus.

My favourite survival trick is one I stole off an

old expedition colleague of mine called Luke.

Our plan, in the event that we encountered

hostile tribes in the Amazon, was for Luke to

whip out his juggling balls and start performing.

We figured nobody would kill someone who

was juggling. As a non-juggler I just hoped

that our assumption also stretched to jugglers

mates. Happily, we never had to find out.

But you dont have to be in a remote or hostile

place to get into trouble. After a late night

a few years ago (and feeling somewhat the

worse for wear) I found myself locked out of

my room in a Central London hotel with no

clothes on (it does seems to be a recurring

theme). With no desire to bare all in reception

downstairs, I just called the lift and pressed

the alarm button. As if by magic, a flustered

employee fumbling a large set of room keys

appeared. Phew. To those unfortunate enough

to share this fate, there are some face-saving

tips on pages .

For me survival has never been about He-Man

strength or Boy Scout preparation. Nor do I

think you need the courage of a bear or the

cunning of a fox. I personally think you can

survive any situation if you treat it like a game.

Games require you to be focused and alert, but

importantly they are just that: games. In this

state of mind, you are less likely to freeze, or

panic and make rash decision, or flap and do

nothing. Your adrenaline will be channelled into

constructive behaviour and the things you do

will seem easier and more achievable. It seems

a subtle change in outlook but its a very,

very useful one.

Enjoy the book and, as the SAS Survival

Handbook used to unhelpfully say, Can you

survive? You have to!

Thanks for that, chaps...

Ed Stafford

edstafford.org

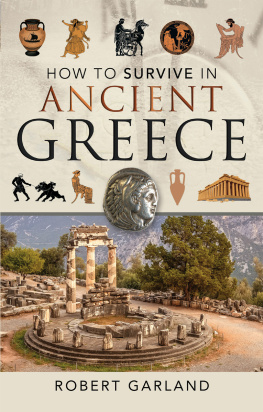

HOW TO SURVIVE AN

earthquake

There are roughly 50 earthquakes around the world every day. Luckily, most of them are

no great shakes, being minor or too small to feel. But there is always an exception, and

the Big One could hit at any time.

Plan ahead. Channel your inner Boy Scout and stock up on