Select one of the chapters from the and you will be taken to a list of all the recipes covered in that chapter.

Alternatively, jump to the to browse recipes by ingredient.

Look out for linked text (which is blue) throughout the ebook that you can select to help you navigate between related recipes.

Snow is a poem. A poem that falls from the clouds in delicate white flakes.

A poem that comes from the sky.

It has a name. A name of dazzling whiteness.

Snow.

SNOW MAXENCE FERMINE

INTRODUCTION

For me, food is as much to do with the imagination as it is with flavor. A dish is more than a collection of ingredients. It comes from somewhere, contains tastes that make you think of the sun or snow, and may be a classic of home-cooking prepared every day in some corner of the world. In short, food comes with associations, with history, and it can take us places.

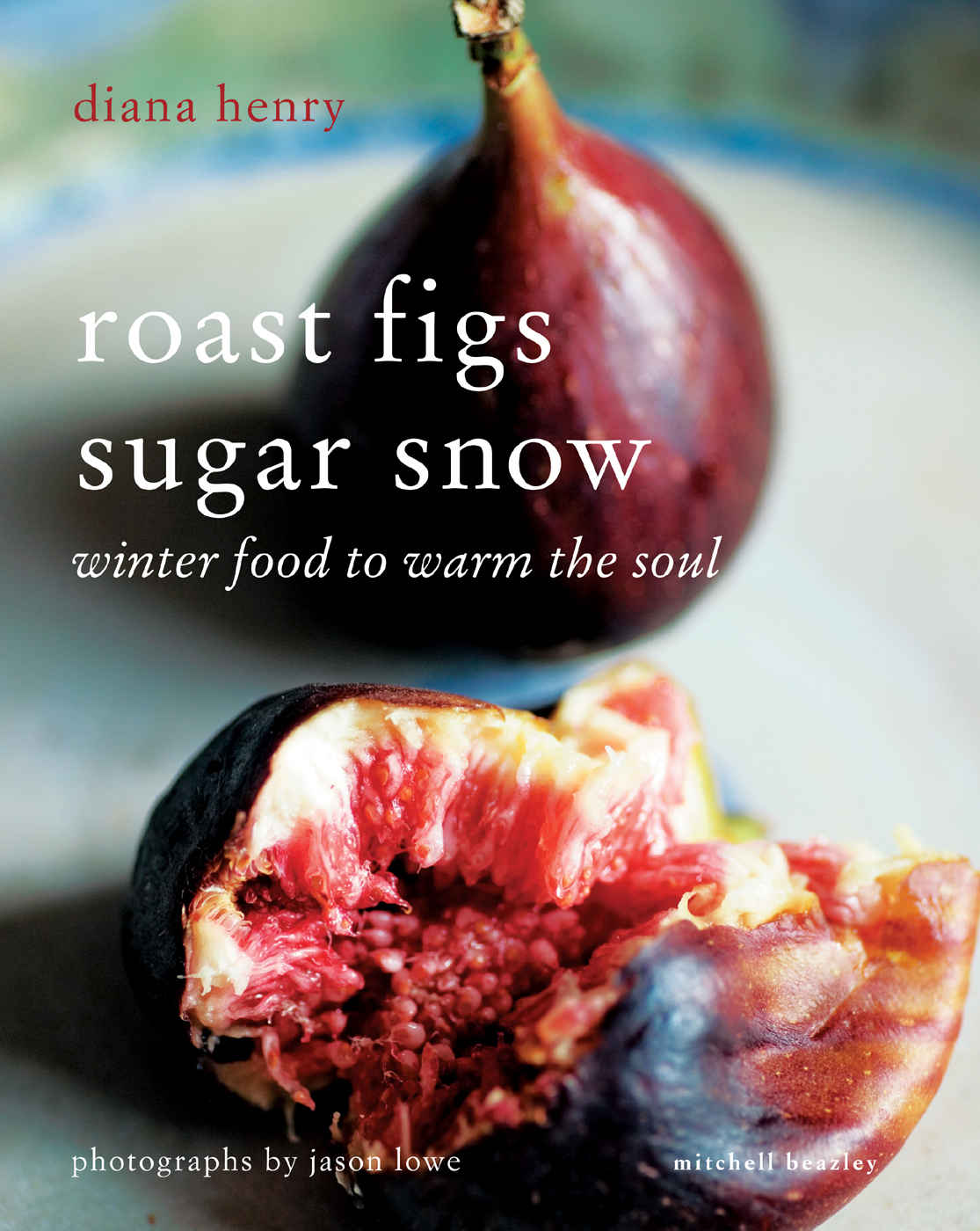

My first book, Crazy Water, Pickled Lemons, was about the enchantment of ingredients from the Middle East and Mediterranean pomegranates, dates, saffron, olives and how exotic I had found them as I was growing up under a cold gray northern Irish sky. My interest was fueled by stories such as The Arabian Nights, and Roast Figs, Sugar Snow has also been inspired by childhood reading, though of books set in a very different world. On dark afternoons, my high-school teacher read us the stories of Laura Ingalls Wilder. In the simple snowy world of the American Midwest found in Little House in the Big Woods, an orange and a handful of nuts in the toe of a sock on Christmas Day seemed as alluring as the seeds from a crimson pomegranate; fat pumpkins gathered in the fall and stored in the attic were fairy-tale vegetables. But it was the story of maple syrup that intrigued me most: how you could tap the sap of maple trees when there was a sugar snow (snowy conditions in which the temperature goes below freezing at night but above freezing during the day), boil the sap down to a sticky amber syrup, and pour it onto snow. There it set to a cobwebby toffee. Here was a magical food that you could get from inside a tree and make into candy. I got my first bottle of maple syrup soon after being read this passage and have loved it ever since.

This book isnt just about ingredients. Its also about the weather and seasons, and the kind of food we want to eat and cook in colder months. Ive always enjoyed fall and winter cooking more than summer cooking. I like the way you gradually turn in on yourself as the weather cools. Life slows down and so does cooking. Cold-weather dishes undergo slow transformations: alchemy takes place as meat and root vegetables, through careful handling and gentle heat, become an unctuous stew, a dish far greater than the sum of its parts. The techniques employed in the kitchen fug the windows and seal you in, and you find you want different foods. You cant argue with your body as it craves potatoes and pulses: the winter appetite is about survival.

Even without their cooking, fall and winter are my favorite seasons. Perhaps it is the result of growing up in Northern Ireland. I find comfort in drizzle and beauty in hueless skies just as much as in the colors of fall foliage and the smokiness of autumnal air. And I adore snow its crystalline freshness, the silent mesmeric way it falls, the way it blankets you in a white, self-contained world. I dont ski, but every winter I set off for some white region to go walking. For a long time I went to the Haute Savoie, where I fell in love with the food: dishes based on molten cheese, game, apples, pears, and nuts. Curiosity about cold-weather flavors took hold of me and I decided to explore other cold places.

In Russia, I found pork served with pickled apples, game birds with beets, and sour cream and curd cheese pancakes with roast plums. (Russian literature is full of food Solzhenitsyn wrote that prisoners in the Gulag desperately wanted to get their hands on books by Gogol and Chekhov, but when they did it was almost unbearable because the descriptions of food were so vivid.) I visited Austria, Switzerland, Hungary, Scandinavia, Northern Italy, America, and other areas of France, collecting recipes as I went, and soon realized what a great hunting ground these countries are for a British cook. They all use much the same basic fall and winter produce as we do root vegetables and brassicas, orchard fruits, pork, game, and cheese but their flavor combinations are different. These trips have had a profound effect on my cooking. The dill in Scandinavia brings a breath of chill air and pine forests to the table; the pairing of horseradish with pork, as in Austria and Russia, makes you see the potential of a root we only bring out for roast beef; peppers and tomatoes cooked with blood-red paprika produces a Hungarian ratatouille that is more suited to winter consumption than the Mediterranean version.

While roasting as many Mediterranean vegetables as the next person, I worry about what the Mediterraneanisation of cooking is doing to the native home-cooking of many countries. It was thrilling to find that, despite the inroads made by this trend, and by fusion cooking, there is plenty of traditional home-cooking going on that doesnt appear to be under threat. The Valle dAosta in northwest Italy offers soups thick with rye bread, venison braised with spices, and orchard fruits cooked in wine, while the Alto Adige region in the northeast has oversized dumplings made with beets, and buckwheat cakes filled with berries. Snowed in one Christmas in Friuli, in the far northeast of Italy, I huddled round innumerable fogolars the big hearths in the center of every Friulian home and innand enjoyed sweet-sour salads of magenta treviso and squash gnocchi showered with crumbs of smoked ricotta, goulash of beef cheeks, and apple strudel.

Time and again I found food like this, food that is unique to its area and impossible to find elsewhere. Perhaps the bodys natural need for solid food in cold weather, coupled with the geographical separateness of mountain regions, has ensured the longevity of traditional dishes in such places. Snow and mountains seem to create and preserve a way of life and a way of eating.