To the man who has been my friend and mentor through thick and thin, who showed me never to be afraid of anything. You taught me not everyone can be educated, that some things in life cant be beaten and to never go downstairs empty-handed.

This is for you, mate.

FIGHTING ISIS

TIM LOCKS

SIDGWICK & JACKSON

PROLOGUE

I studied the village of Batnaya, three kilometres away across the huge open expanse of flat, dusty, barren land. Squinting, I could make out signs of movement around the water tower, the whole scene shimmering in the afternoon heat.

Resting my elbows on the edge of the roof, I raised the scope and zoomed in until I was able to pick out some tiny figures. All the men were kitted out in black and carrying a black flag between them. Daesh.

This was my first day on the front line in Iraq. Finally, after battling months of frustrating red tape, I was here, and the enemy I had come to tackle was within sight.

You know the General has already lost three of his brothers to Daesh? asked Marcus, a local Assyrian from Dwekh Nawsha, the Christian militia group I was affiliated with. One of them was killed by a mortar round in the trench just down there, along with three of his men.

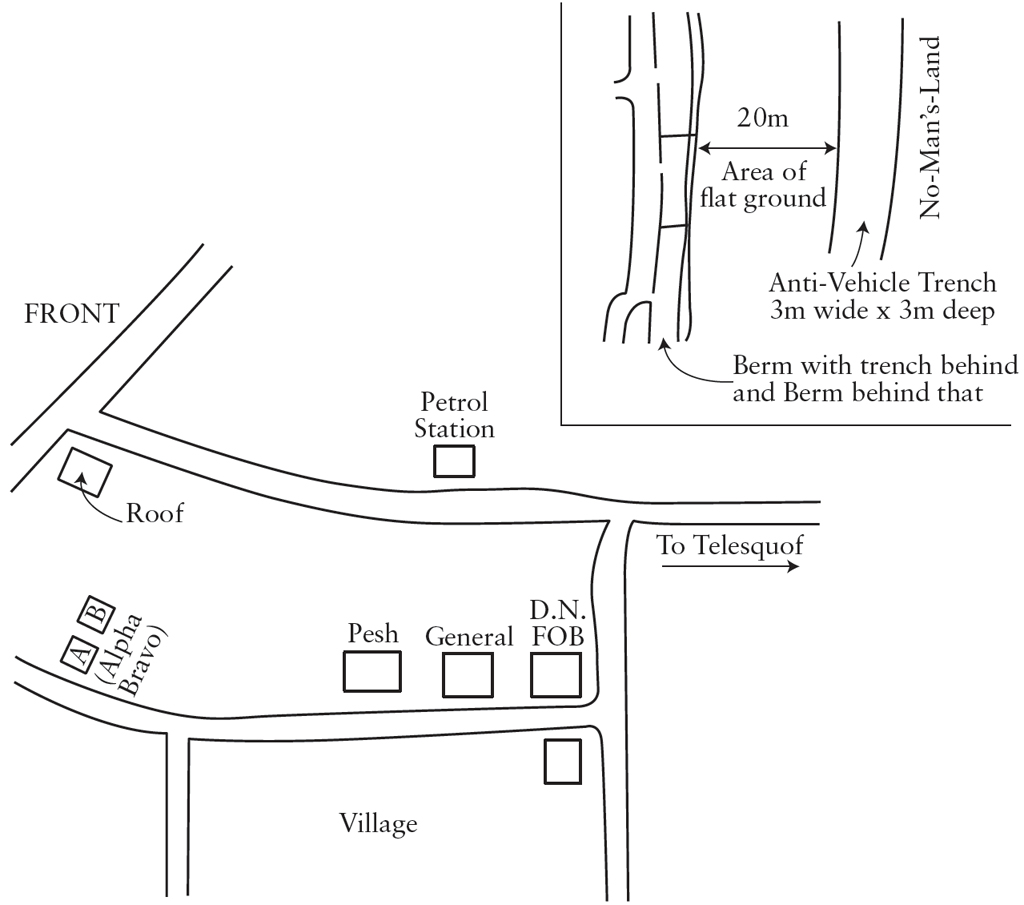

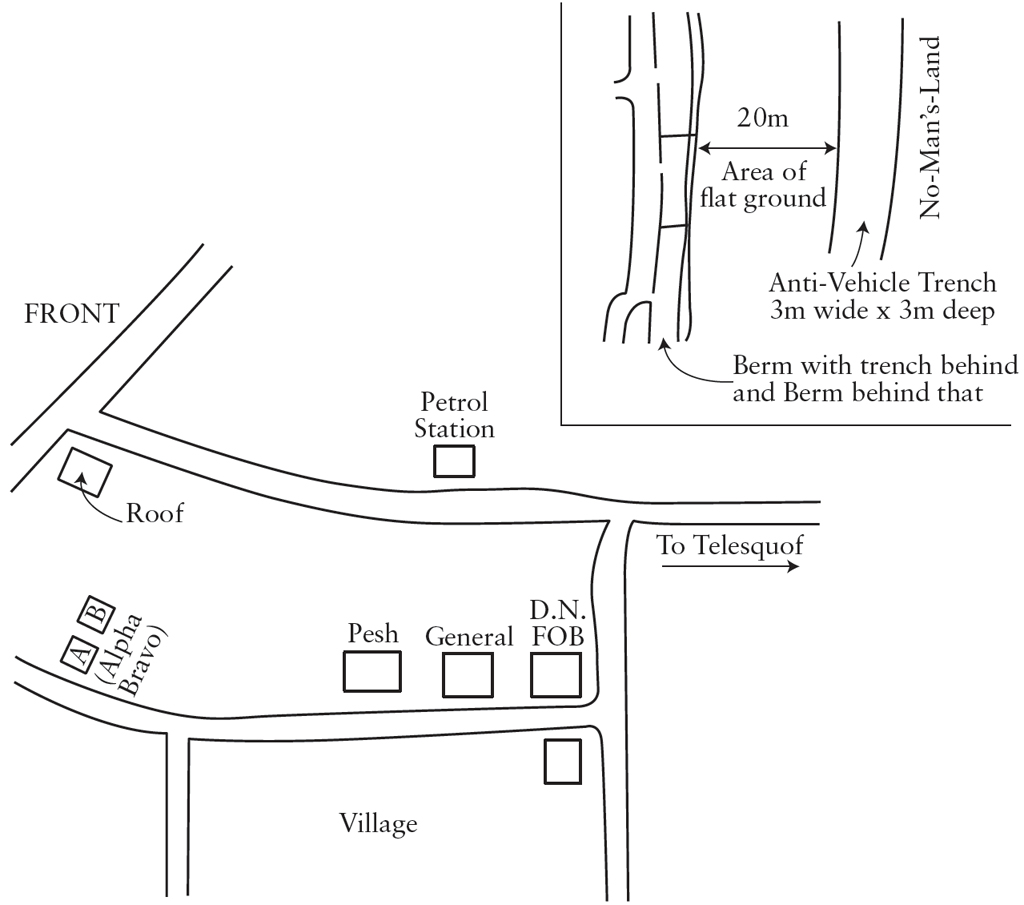

He gestured to the trench that lay in front of us. It had a berm behind it and in front of it, and twenty metres nearer to no-mans-land, which divided us from Daesh territory, was the anti-vehicle ditch, three metres wide and deep, dug during the fighting with Daesh. No question that the mortars could reach this far then, I thought. There was a road that wound between Batnaya and our village, Baqofa, the only sign that life hadnt always been this way. No longer used, it was starting to disappear beneath the swirling dust.

Pushing off the wall, I headed back across the roof of our house to join JP, a fellow Brit, who was my closest friend in the group. The house had been abandoned by fleeing locals and was now being used to coordinate frontline action and offer support to any activities on the ground. It was being manned by the Peshmerga the Kurdish army with the help of Dwekh Nawsha.

Ive just been told that when we fire mortars at them, the aim is ultimately the water tower, JP told me. But anywhere in the village is fine, just not the church. We avoid the church at all costs.

He shrugged as he spoke, knowing we would both be thinking the same about that instruction. Neither of us was here for religious reasons, but rather because we wanted to help stop the slaughter of innocent people and destroy Daesh. But if that was their rule, we could live with it.

I had just pulled my phone out and begun taking photos of the area when suddenly there was a thud, and a thick cloud of dust sprang up from the ground four hundred metres away. A mortar! Adrenalin and excitement kicked in, making me instantly alert. I turned my phone in the direction of the dust, determined to record the first mortar round of my life.

There was a whoosh, and a second thump another mortar round had slammed into the ground closer to us, this time around three hundred metres away. Wed been told no action was expected until night-time, when temperatures were cooler and both sides preferred to be active, but it looked like things were about to get interesting. This was most probably because Daesh had seen that we (the volunteers from the West) were there. They watched us as much as we watched them, and had better kit with which to do it.

Then a third round came rushing in and landed two hundred metres away. Immediately the atmosphere on the roof changed.

Fuck, they are dialling in on us. Get off the roof! shouted Cory, a former US Army Ranger. It seemed they were aiming for our building, and a spotter was helping adjust the angle of the weapon one click at a time to hone in on their target us.

The Americans and several of the Peshmerga soldiers ran to the side of the roof and sprinted down the concrete stairs shaped against the building (as handrail or guard) to get away, clearly fearful that the next mortar would be on target.

I looked around and stopped for a few moments to consider the options. I was in Iraq as a volunteer fighter, so I had no army commander to tell me what to do. Every decision I made was to be my own, and with no previous military experience it was all about using common sense and keeping level-headed. I followed suit and ran down the stairs.

Once on the ground I paused to see some people had disappeared towards the berm, a long thin earthen hill running parallel to and about twenty metres back from the vehicle trenches. Soft ground is a good area to be during mortar fire, as a mortar will go into the ground and explode, not bounce around as it can do on concrete. I hadnt experienced this first-hand yet, but I had done my research. I did, after all, want to survive out here.

The Americans were over to my left along with Marcus, and some of the Peshmerga were to my right, but there was a big gap opposite the abandoned road. If this was a pre-emptive strike before Daesh came in vehicles, I was sure this would be their route. If I set up there, I could take out as many Daesh as possible when they appeared in view.

Just then another mortar exploded, sounding even closer to us than the last. Keeping low, to make myself as small a target as possible, I sprinted to my destination. At least I attempted to sprint I had 40 kilogrammes of kit weighing me down, as I had come out prepared for any eventuality. I had my Osprey combat vest on body armour that covered my chest and my machete was tucked in behind my shotgun. My Glock 19 was in a high leg holster, and my shotgun was on my back in a holster I had fashioned myself from an old Camelbak. It was on my Osprey on my back, and I had twelve magazines of 7.62mm ammunition for my AK47, six magazines of 9mm for my Glock, a pouch of approximately twenty shells for my shotgun, my personal medical kit and my personal admin pouch. We had got ourselves all kitted up, working on the proviso that until we knew what it was like on the front line, it was better to be prepared for anything. Most kit stays in the FOB you basically carry ammo, water and meds.

I dived into a nice depression, and lay flat on the soft ground, shoving the front grip of my AK into the dirt and setting up my equipment around me. I was desperate to see Daesh heads appear over the horizon.

Wiping sweat from my brow the heat had reached 45 degrees by now I turned my comms on and radioed through to JP, who I could see still standing on the roof behind me. He responded, and to my surprise was laughing his head off.

Big T, you are the first civilian I have ever seen running towards mortar fire. Im not sure if that makes you crazy or brave.

Why are you still on the roof? I asked, laughing too with the adrenalin of it all.

Tex has run to the mortar to man that. Im going to direct him, and I can do that best from up here with the scope.

JP is ex-army, pragmatic, fearless, and of the opinion that if it is your time to die, it is your time, and that is that. So the fact he had stayed on the roof, prioritizing his role over his own safety, made sense to me.

Just then, Dushka fire also started to ring out over my head. These are long-range 12.7mm machine guns; they are one of the weapons of choice of both sides, and make a hell of a noise. I flattened myself into the soil. They clearly meant business.

But despite the bullets flying overhead, I couldnt help a smile. This is what I had wanted for so long, what I had spent months planning for to get to the front line and defend innocent people against the horrors of Daesh. Now, finally, it was happening.

Next page