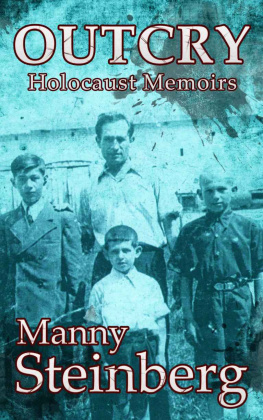

Copyright 2014

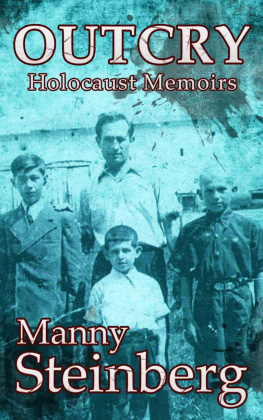

In memory of my Mother, Ethel

And Brother David (Dulo)

T hese are his memoirs for the years 1939 through 1944. It is a story of survival, but much more. It includes observations and commentary in the political, social, and economic climate of the time. Some background historical commentary (Poland before to World War II) set the scene. Memoirs are shared of the old flavor (Pre-war) of his small town of Zolkiew. The social life, active business, including the Zolkiew-Paris connection in the production of furs, town personalities, the street hustle and bustle, fashion, education, poverty

He describes the dramatic changes of life in the town under the Russians and the Germans. He includes a description of his architectural studies in Lwow, fellow students, famous professors, the political atmosphere there, and educational opportunities under the Soviets.

He temporarily found safety working in the small border town of Mosty Wielkie as a technician on a railroad project. He took to the forest with his family when conditions for Jews got progressively worse in town. He details descriptions of survival in the forest, near death experiences, dangerous excursions to find food, and the relationship with other Jewish groups hiding in the forest.

He hid with his family in the village of Zaxonie, located in the middle of the forest, by friendly Poles (the Dabrowski family). They persevered in spite of being hunted by Germans and the Ukrainian bands. He was armed and was ready to fight for his life and those of his family. He described the very close special bond he had with his mother, Ethel, and brother, Dulo (David), a true hero, who arranged all connections with the non-Jewish world.

I t was the spring of 1941. A small town in eastern Poland, located near the new border between the U.S.S.R. and Germany, on the Soviet side. The border was established in 1939, after the partition of Poland between these two countries.

It was like a stage during the change of a scene.

Concealed messages in the letters, received from the German side of the border, informed on troop concentration , and that an attack by the Germans was imminent.

Zolkiew, a town of about 10,000 inhabitants, mostly Jewish, was historically connected with the Polish past. Named after the Polish hero of the battles in the middle ages against the Turks and Tatars , Hetman Stanislaw Zolkiewski, it preserved some architectural jewels of its past with a 16th century church with a renaissance tower, fragments of the old defense walls with gates, with drawbridges leading to the town. In the church used to pray the famous Polish King Jan Sobieski, the participant in the battle against the Turks at the gates of Vienna in 1693. Preserved were also the remnants of the medieval castle, where Hetman Zolkiewski and his family lived, the town square, surrounded with arcades, hiding in their shade small stores, mostly Jewish. In the Jewish quarter of the town was a magnificent renaissance synagogue, built in the 17th century with the permission of the king, Jan Sobieski.

Before World War I, as a result of the partition of Poland between Russia, Austria , and Prussia at the end of the 18th century, the town was part of the Austrian province Galizien.

Life here changed little between the wars. The old generation of the population was nostalgic about the old, good, peaceful times of the Austrian Emperor Franz Joseph. In fact, it w as a semi-feudal society, with the majority of Ukrainian peasants in the countryside mostly illiterate, living in misery, while the Polish landowners, the gentility, owned most of the land.

After Poland reg ained independence little changed, except that official anti-Semitism crept into the towns life, an excuse used for Polish inefficiency and backwardness.

The Ukrainian population was in a process of national awakening and, under the influence of their clergy and intelligentsia, considered the Poles with hostility, as occupants, hoping for another chance for a historical reckoning. Since the last so called Polish-Ukrainian War in 1918, Hitler, at the gates of Poland, gave them new hope for liberation, liquidation of the Polish population and, of course, the Jews. They had their days during the battles for independence against the Poles in 1918, when their occupying bands were busy with pogroms of the Jewish population. The Poles who were fighting the Ukrainians, notably the army of General Joseph Haller, also found an outlet in persecuting the Jewish population, beating anyone who looked Jewish or cutting off their beards and side locks.

Due to a historical aversion of the Poles toward commerce, the Jewish population dominated most of the small businesses in these towns . A few were rich, but a vast majority were poor, barely making a living: artisans, carpenters, tailors, shoemakers, painters, furriers. Among the well-to-do were a small number of lawyers, doctors, and skilled educated professionals. A separate group, the Chassidic Jews, lived together in their quarters, and only God knows how they made a living. Here poverty was in the extreme. Probably the hope for the arrival of the Messiah kept them alive. I still have before my eyes a picture of a cheder, a room full of kids repeating mechanically after the rebbe the phrases of the Torah. In the corner of the room was a table designated for the breakfast brought by the boys from home. In most cases it was a piece of bread clumsily cut from a loaf, some slices spiced with garlic, rubbed into the crust of the bread, some with butter spread thinly, just for looks. Some boys came empty handed, hungry.

The Poles and Ukrainians felt comfortable in their anti-Semitic attitude. They saw that a vast majority of the Jewish population was poor, struggling to make a living; they used the services of the talented Jewish professionals and were aware of the positive role these people were playing in their lives. It made them feel good that there was somebody below their status. Their clergy never let them forget that the Jews killed Jesus Christ. For them it was insulting heresy when told that Jesus Christ was Jewish. It was interesting to observe these dirty Jews, as they called them, run every Friday afternoon to their bathhouses with saunas to make themselves clean for the Sabbath, while personal hygiene of the vast majority of peasants was nonexistent, who very seldom had a chance to take a bath, except in the summer, if they lived near a river or a lake.

At the outbreak of the War, a vast majority of the Jews in Poland lived in these small towns. The Polish establishment, the feudal landlords, the clergy, the military and well-to-do Poles kept feeding this fire of hatred, diverting the attention of the non-Jewish population from their selfish interests.

We ought not to forget the fact, very often nowadays kept away from the public, that the Polish rulers, with the substantial support of the population, cooperated with Nazi Germany to the last few months before the outbreak of the War. Let us also not forget that Poland participated in dismembering a Slavic country, Czechoslovakia, in the spring of 1939, liberating Zaolzie, while Hitler marched into the Sudetenland.

Polish rulers, the reactionary Roman Catholic Church, the Ukrainian clergy, and the nationalistic Polish and Ukrainian intelligentsia prepared a fertile ground for Hitler for the extermination of three and a half million human beings- men, women, and children, only because they were born Jewish.

H ersh Leybele was a fragile, little Orthodox Jew, about five feet tall. Often one could see him wandering around the town, talking to himself, scratching his small red beard, which Orthodox scholars sometimes do during studies, to help themselves solve difficult Talmudistic problems. Dressed in a worn-out black coat, a small, round, black hat sitting askew on his head, Hersh Leybele ignored people around him, as long as they did not bother him, looking with his big, blue eyes at a distant point, without showing any emotions.

Next page