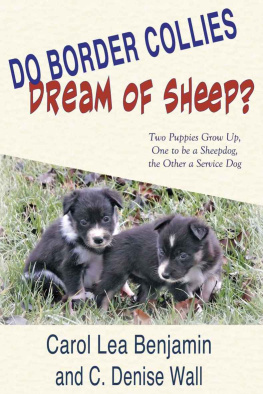

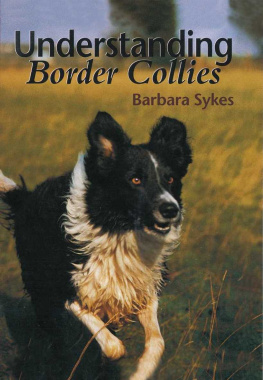

Do Border Collies Dream of Sheep? is the story of how the wolf became the dog and how the dog became our very best friend. It's about two working dogs, how they learned their life's work and how the skills they inherited and the lessons they were taught helped them along the way. This is how two littermates grew up and became very different and yet stayed very much the same. This is the story of May and Sky.

Lassie Come Home, Adams Task, The Plague Dogs, White Fang, Winterdance: classic dog books inhabit a mysterious, magical space where two unalike species love and comprehend one another. Do Border Collies Dream of Sheep? is such a classic.

Carol Benjamin and Denise Wall have written a beautiful, fascinating book; a book that does full honor to all dogs. ~ Donald McCaig

Two Puppies Grow Up, One to be a Sheepdog, the Other a Service Dog

Photographs by C. Denise Wall, Carol Lea Benjamin, Stephen

Lennard, Christine Henry, Robin French, and Zachary Joubert.

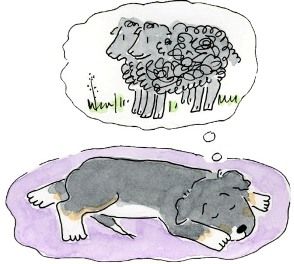

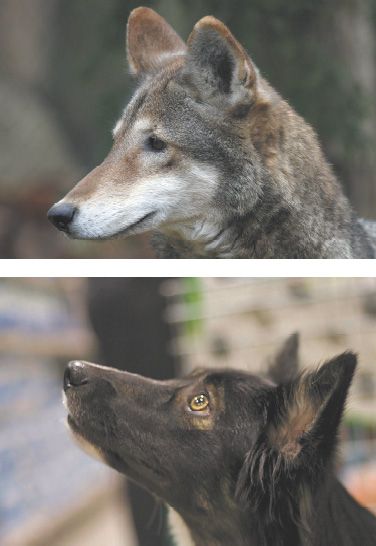

Wolf photographs by Monty Sloan and Denise Wall

Illustrations by Carol Lea Benjamin

Carol Lea Benjamin and C. Denise Wall

Contents

1

Carol

This is the true story of two border collies who were born on a small farm in North Carolina, both destined to become working dogs. One would remain on the farm to work sheep, like her parents, her grandparents, and all her ancestors before her. The other would become a service dog, a dog who helps a person with a disability, in one of the biggest, busiest cities in the world. Herding is one of the oldest partnerships between human beings and dogs; service work is one of the most recent. Yet both dogs would need to employ instincts from their wild ancestors in order to succeed at their work. So this is a very modern tale that reaches way back in time.

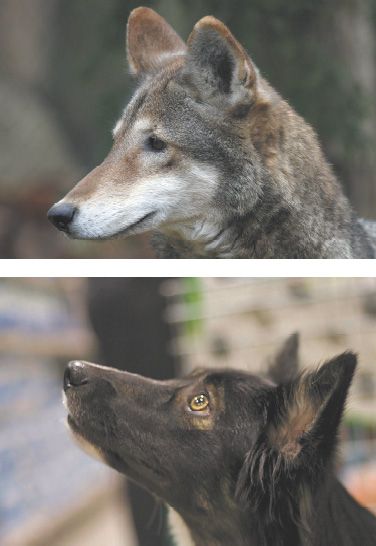

Before the dog, there was the wolf.

Except for their tracks in the snow or in the muddy earth beside a stream, wolves were rarely seen by our earliest ancestors, but in the dead quiet of the night, the eerie sound of their howling might have echoed off the cold stone walls of what was then human housing. For safetys sake, the wolves kept largely to themselves. Others of their own kind were seen as competition for territory and the prey that could be found there. Those who were different were potential meals. What was safe was what was familiar, what was family.

Wolf packs were, in fact, extended families, a male and female and their offspring. When the pups matured, some stayed with the pack, while others, more than likely the boldest ones, left to form packs of their own. Sometimes an outsider would show up, some wolf whod left another pack. In that case, the wolves might chase him off, or if he was persistent enough not to leave, they might kill him. Occasionally the pack would accept a stranger. This was a double-edged sword. With more wolves to cooperate in the hunt, the pack might be more successful. But in lean times, there would not be enough game to feed a larger family. So it was usually only the alpha or dominant pair who bred. They were the strongest and the wisest of the pack, the best genetic specimens, so their pups would have the best chance of thriving. Life was harsh and life expectancy was short. Population control helped ensure the pack would go on. In the wild, everything is about survival. Toward that end, the dominant pair kept the peace, made safety a priority and led the hunt. They set the mood, initiated all the important activities, and, along with the other adult members of the pack, protected the pups from danger, provided them with food, and taught them the skills they needed in order to survive.

Wolves have no sophisticated verbal or written language like the kind humans eventually developed. Instead, they use a complex system of body language to communicate with each other. They understand the smallest gestures, facial expressions, postures, even ear and tail positions. It is body language that gives the wolves the clues they need to navigate their world, helping them understand other individuals within the pack and also those outside the pack, other wolves who might invade their territory and the prey animals they are hunting.

Their keen senses are part of their efficient and effective system of communication and also help them survive. They can hear each other howling from several miles away, can spot movement at great distances, can see better in the dark than we humans can and their sense of smell is about one hundred times more sensitive than ours.

All the wolves skills and senses come into play when they hunt for food. Their excitation is palpable and while an observer might not be able to discern how they know the intentions and plans of the others in their pack, they work almost as if they are one being, staying focused on their goal and working as a team until the hunt is over.

When the wolves spot a herd of prey animals, they stalk the herd, circle it and finally get all the animals running. With the herd on the move, the wolves are able to make an educated guess as to which animal to single out, which one they would have the best chance of catching. Often, but not always, it is one that is weak in some way, very young, old, slow, sick, or lame.

After the wolves separate an animal from the herd, they might surround it. For a moment, predators and prey freeze. No one moves while they assess each other, looking for strengths and weaknesses that will help each side determine how to proceed. The prey animal might take off, running for his life. Or he might hold his ground, deciding to fight instead of fleeing. The wolves might close in, or, feeling the strength and determination of the prey animal, they might leave, hoping for better luck next time around.

No matter how well the wolves cooperate with each other or how hard they work, the hunt is not always successful. When the wolves fail to bring down prey, they go hungry. When the hunt goes well, the wolves share a much-needed meal, gorging themselves in part because wolves in the wild can never be sure when the next meal will be, in part because often there are hungry pups waiting at home.

As soon as the adults get back to the den, the pups mob them, jumping up and licking at their mouths. This triggers the grown-ups to regurgitate some of what they have eaten, giving the pups a feast of their own.

Next page