HUDSON STREET PRESS

Hudson Street Press, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

USA | Canada | UK | Ireland | Australia | New Zealand | India | South Africa | China

penguin.com

A Penguin Random House Company

First published by Hudson Street Press, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC 2015

Copyright 2015 by Thupten Jinpa Langri

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

REGISTERED TRADEMARKMARCA RE GISTRADA

REGISTERED TRADEMARKMARCA RE GISTRADA

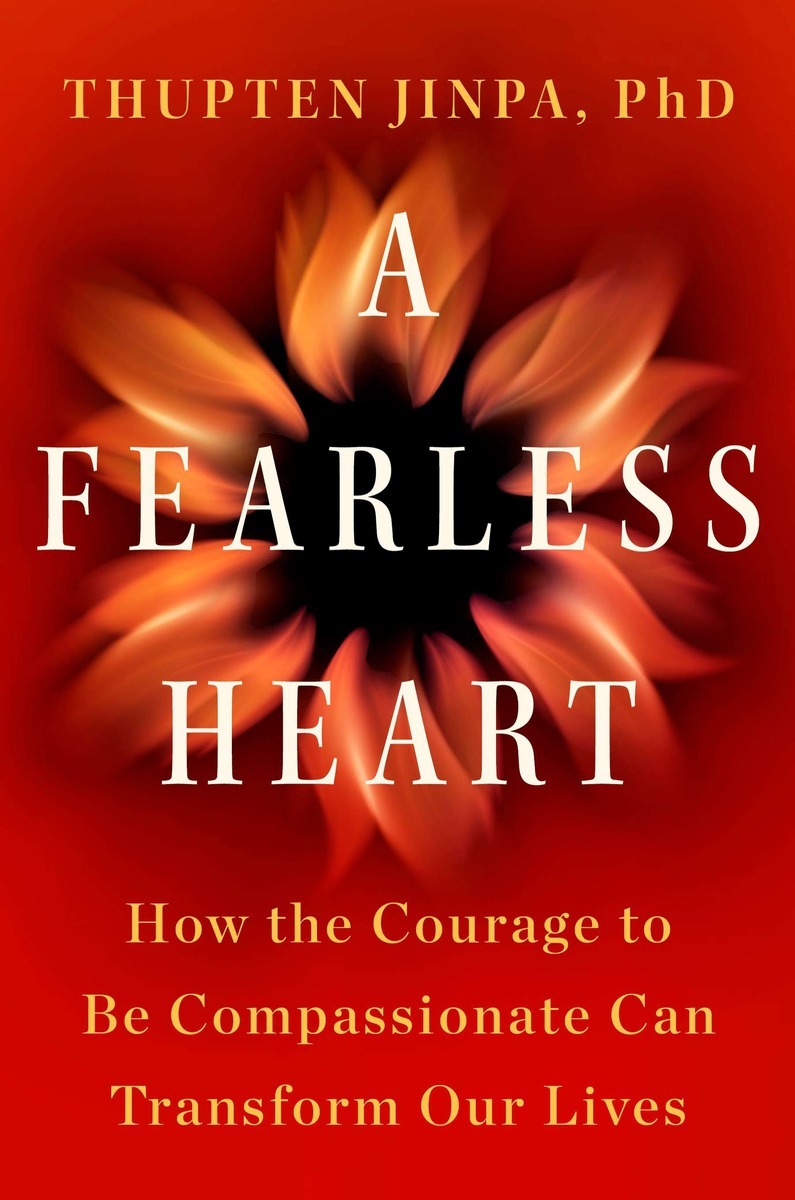

Cover design: Jaya Miceli

Cover image: Davies and Starr / Getty Images

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING - IN - PUBLICATION DATA

Thupten Jinpa.

A fearless heart : how the courage to be compassionate can transform our lives / Thupten Jinpa.

pages cm

ISBN 978-0-698-18646-0

1. Self-actualization (Psychology) 2. Compassion. 3. Mind and body. I. Title.

BF637.S4T5294 2015

177'.7dc22

2015005279

While the author has made every effort to provide accurate telephone numbers, Internet addresses, and other contact information at the time of publication, neither the publisher nor the author assumes any responsibility for errors or for changes that occur after publication. Further, the publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party Web sites or their content.

Version_1

To my late parents, who despite all their hardships

as Tibetan refugees in India, instilled in me faith

in the basic goodness of humanity

I NTRODUCTION

Nothing is more powerful than an idea whose time has come.

V ICTOR H UGO

I remember walking excitedly next to His Holiness the Dalai Lama, holding his hand and trying to keep up with his pace. I must have been about six when the Dalai Lama visited the Stirling Castle Home for Tibetan Children in Shimla, northern India. I was one of more than two hundred children of Tibetan refugees resident there. The home was set up by the British charity Save the Children in 1962 in two former British colonial homes located on a small hill. We children had been busy preparing for the visit, rehearsing welcoming Tibetan songs while the grown-ups swept the road and decorated it with Tibetan symbols in white lime powderlotus, infinite knot, vase, two goldfish (facing each other), eight-spoke wheel of dharma, victory banner, parasol, and conch. The day the Dalai Lama came, there were many Indian policemen around the school; I remember playing marbles with a few of them that morning while we waited. When the moment finally arrived it was magical. Thick smoke billowed from a whitewashed incense stove built especially for the occasion. Dressed in our colorful best and holding kata, the traditional Tibetan white scarves of greeting, in our hands, we stood on both sides of the driveway leading up to the school and sang at the top of our lungs.

I had been chosen as one of the students to walk alongside the Dalai Lama as he toured the school. While we walked, I asked him if I could become a monk, to which he replied, Study well and you can become a monk anytime you wish. Looking back, I think the only reason I was so precociously attracted to being a monk was because there were two monk teachers at the childrens home. They were the kindest of the adults there and also seemed the most learned. They always looked happy and at peace, even radiant at times. Most important for us children, they told the most interesting stories.

So when the first opportunity came, at the age of elevenand as it happened, on the first day of Tibetan New Year (toward the end of February, that year)I became a monk and joined a monastery, despite my fathers protestations. He was upset that I was squandering the opportunity to become the family breadwinnerparents of his generation wished for their children to get an education and work in an office. For nearly a decade afterward, I lived, worked, meditated, chanted, and belonged in the small community of Dzongkar Choede monastery. It was there in the quiet evergreen hills of Dharamsala, northern India, that I practiced my rudimentary English with enlightenment-seeking hippies.

I developed friendships with John and Lars. John was not a hippie. He was an American recluse who lived alone in a nice bungalow hed rented close to the meditation hut of a revered Tibetan master. I met with John once or twice a week. We would speak and I would read from a Tibetan text, which itself is a translation of an eighth-century Indian Buddhist classic. It was John who introduced me to pancakes and ham.

Lars was a Danish man who lived quite close to the monastery. Often I would visit him to chat and have toast with jam.

In the spring of 1972, the monastery moved to the scorching heat of southern India, where a Tibetan resettlement program had begun. There, like the other monks of my monastery, at the age of thirteen, I joined the resettlement workforce clearing forests, digging ditches, and working in the cornfields. For the first two years, while the settlement was being prepared, we were paid a daily wage of 0.75 Indian rupees, or roughly 1.5 cents.

There was very little formal education at Dzongkar Choede. Its not the custom for young monks to go to regular secular schools either. By the time our community moved to South India, I had finished memorizing all the liturgical texts that were required. The days labor at the settlement finished by four in the afternoon, so I had some free time on my hands and I decided to pick up my English again. However, with no opportunities to practice conversation, I made do with reading comic books. One day, I obtained a cheap used transistor radio, and after that I listened to the BBC World Service and U.S.-based Voice of America every day. In those days, VOA had a unique program broadcasting in special English, in which the presenter spoke slowly and repeated every sentence twice. This was immensely helpful, as I had only a very basic grasp of the language at the time.

Since I was the only young boy at the monastery who could speak and read English, rudimentarily though it was at first, it was a source of pride and also a way of individuating myself from the others. Here was a worldfiguratively and literally the whole world beyond the refugee community, beyond the monasterythat I alone from my monastic community could enter. Through English I learned to read the globe, which made all the great countries I was hearing about in the news come to lifeEngland, America, Russia, and of course, our beloved Tibet, which had tragically fallen to Communist China.

REGISTERED TRADEMARKMARCA RE GISTRADA

REGISTERED TRADEMARKMARCA RE GISTRADA