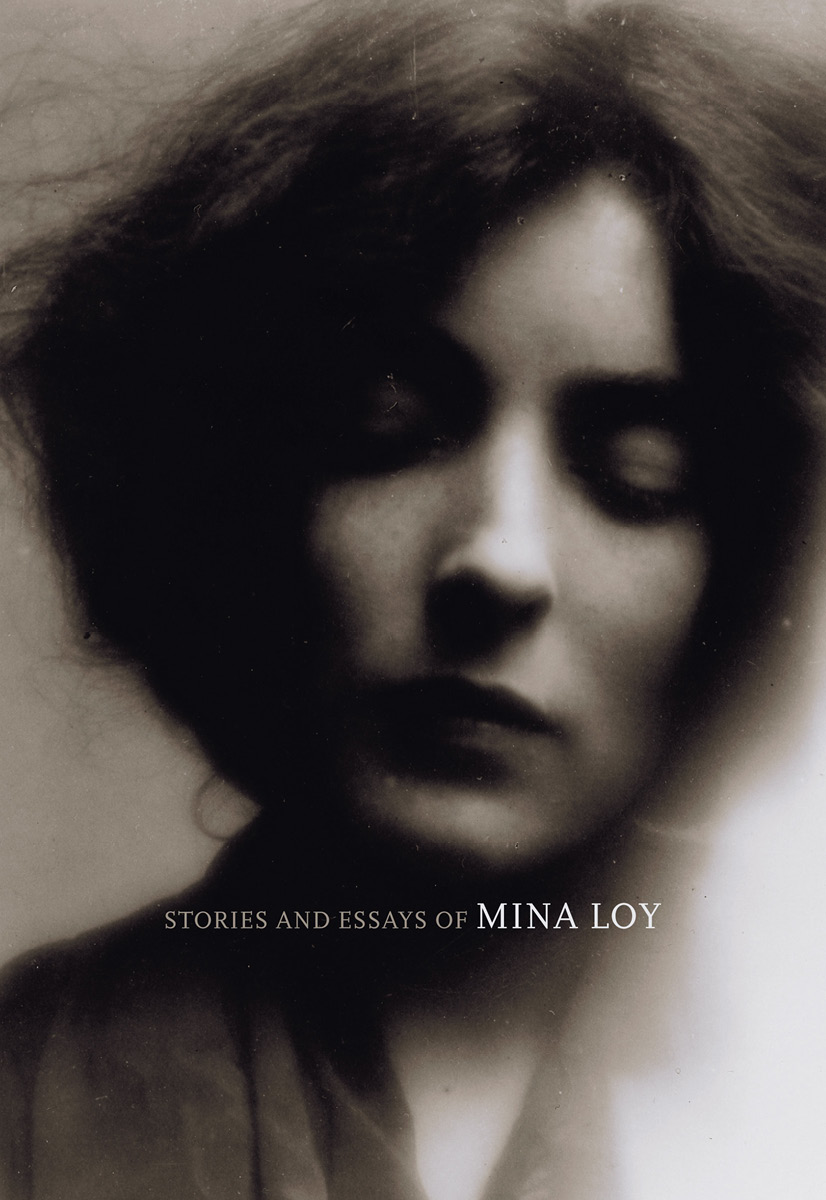

STORIES AND ESSAYS OF MINA LOY

EDITED BY SARA CRANGLE

DALKEY ARCHIVE PRESS

CHAMPAIGN DUBLIN LONDON

OTHER WORKS BY MINA LOY

Songs to Joannes (Others magazine, 1917 )

Lunar Baedecker [sic] (Contact Editions, 1923 )

Lunar Baedeker & Time-Tables (Jonathan Williams/Jargon Press, 1958 )

At the Door of the House (Aphra Press, 1980 )

Love Songs (Aphra Press, 1981 )

Virgins Plus Curtains (Press of the Good Mountain, 1981 )

The Last Lunar Baedeker ( The Jargon Society, 1982 )

Insel (Black Sparrow Press, 1991 )

The Lost Lunar Baedeker (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1996 )

TABLE OF CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Born in London in 1882, Mina Loy was an artist, inventor, novelist, actor, and prose writer, but as yet, her foothold in modernist history is secured by her poetry. Loy remains best known for a collection of poems entitled Lunar Baedecker that she published in Paris in 1923. The title poem is a travel guide to a lunar landscape that is decadent and deteriorating, a heady combination of modern and ancient. Here, Delirious avenues are

lit

with the chandelier souls

of infusoria

from Pharaohs tombstones

Loys cityscape contains not a red-light but a white-light district of lunar lusts; the moon hosts a desire strangely bled of colour and vitality. As the poem nears its conclusion, its setting is likened to a fossil virgin and a Crystal concubine ( Lost LB 812). This moon encompasses the prehistoric, petrified remains of plants and animals, as well as a state of inviolate chastity, a newness and navet; Loys is a celestial object made of a substance so pure and transparent it is associated with prophetic powers, but is simultaneously akin to a kept woman sullied by her dependency on a man. This poem shows Loy at her oxymoronic best; in part, it is her fondness for surprising, even disorienting juxtapositions of high and low that defines her writing as modernist. These self-same practices arise time and again in Stories and Essays of Mina Loy , a volume that aims to broaden awareness of a writer and her era.

Mina Loy was unquestionably immersed in the key events and radical aesthetics of her time. She studied art in London and Berlin respectively, becoming a member of the prestigious Paris Salon in 1906; in 1913, Loy befriended the leaders of Futurism F. T. Marinetti and Giovanni Papini; in World War I, she nursed the wounded in Italy; in 1916, Loy moved to New York and immediately became part of the circle of avant-garde artists regularly entertained by Walter and Louise Arensberg, a group including Dadaists Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray; in the 1920s, she started a lamp-making business in Paris with the financial backing of the American art collector Peggy Guggenheim; in the 1930s, she worked as the representative for her son-in-law, Julien Levy, purchasing surrealist art in Paris for his New York gallery; in 1959, on the basis of six decades of creative productivity, Loy received the Copley Foundation Award for Outstanding Achievement in Art. Loy participated in artistic communities on three continents, and even the most cursory list of her associates reads like a compendium of modernist greats: among many others, Loy knew Djuna Barnes, Natalie Barney, Basil Bunting, Joseph Cornell, James Joyce, Alfred Kreymborg, Robert McAlmon, Marianne Moore, Alfred Stieglitz, Gertrude Stein, Carl Van Vechten, William Carlos Williamsand, pivotally, her husband Arthur Cravan. Throughout her life, Loy wrote avidly: her work appeared in era-defining periodicals such as The Little Review the journal that first published extracts from Ulysses and The Dial , which debuted T. S. Eliots The Waste Land . Loys work was reviewed and praised by Eliot and Yvor Winters; she was lauded, edited, and published by Ezra Pound.

Loys widespread recognition suggests that her place must be firmly anchored in twentieth-century literary history, but as modernism became an aesthetic construct, Loy did not become part of its canon, a fate she shared with many of her female peers. Loy died in 1966 having published only two books: Lunar Baedecker (1923) and Lunar Baedeker and Time-Tables (1958). One of Loys most ardent fans, Rexroth triumphantlyand prematurelyannounced Loys return to the cultural map in 1971. She has been rediscovered, Rexroth writes, and when the present generationthe counter culturecan find her poems, they are read with enthusiasm (72). How can a writers work be reclaimed if it cannot even be located?

This difficulty was addressed in part in 1982, when Roger L. Conover edited the third volume of Loys writing, The Last Lunar Baedeker . This edition, now out of print, remains the most complete; it contains Loys long autobiographical poem, Anglo-Mongrels and the Rose, as well as a great deal of previously uncollected poetry and prose. In 1996, Conover published another book, entitled The Lost Lunar Baedeker . While shorter than the 1982 volume, the later collection is the most widely available and accurate to date; it restores, for instance, the layout and punctuation of Loys celebrated poem sequence, Songs to Joannes. In the twenty-first century, everyone wants a piece of Mina Loy.

As the publication of this volume indicates, the reclamation of Loys oeuvre is far from over. Stories and Essays includes the vast majority of shorter prose stored in Loys papers at the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale; not one of these writings has been collected, and most of them have never been published. But this book is by no means a complete survey. A number of Loys key prose writings are already available in Conovers two Lunar Baedekers , which include Loys Aphorisms on Futurism the much-anthologised Feminist Manifesto, and landmark essays such as Modern Poetry. Again, the availability of her writing, and lack thereof, has had a considerable hand to play in the shaping of Loys reputation.

This dearth of published material has meant that most readers remain unaware that Loy the poet was an equally active writer of narratives, criticism, and cultural commentary. Loy wrote her first poem, The Beneficent Garland in 1914; in this same year or the next she began the play The Sacred Prostitute; shortly thereafter, she embarked upon another drama, The Pamperers. While dates of composition are rarely given in Loys papers, certainties include 1921 for The Stomach and The Oil in the Machine? as well as 1925 for one draft of Gate Crashers of Olympus. Loys lecture Gertrude Stein was given at Natalie Barneys salon in 1927, and there exists good evidence that In Maine: Greens Colony was written in the late 1920s or early 1930s. Loys thoughts on William Carlos Williams were mailed on June 5th 1948, while Tuning in on the Atom Bomb is evidently a product of World War II or its immediate aftermath. Lastly, Carolyn Burke claims that History of Religion and Eros was written during the years that Loy lived in New Yorks Bowery District, namely 19481953 ( BM 42223). A completely accurate chronology of the narratives and essays in this volume may never be compiled, but these dates alone clarify that Loy was writing a great deal of prose from the outset of World War I until the 1950sthe very period that encompasses her most productive writing years. Ideally, this book will thus contribute to a realignment and expansion of Loys poetic legacy.

Stories and Essays will certainly confirm Loys standing as a modernist. Loy directly addresses topics shunned by her forebears or considered anew by her contemporaries, including abortion, aesthetics, avant-gardism, the body, class, consumption, evolution, gender relations, genius, iconoclasm, metaphysics, power, sexuality, subjectivity, transcendence, and war. Artistic and ideological movements like Futurism Imagism, and Dada also make appearances. Loys criticism continues these preoccupations, and extends them to figures central to the shaping of modernism such as Brancusi, Braque, Eliot, Havelock Ellis, Freud, Joyce, Lawrence, and Picasso. But more than these ready associations with the modernism to which Loy is so often allied, these works illustrate how Loy gradually came to question twentieth-century mores. Some readers may be surprised to discover Loy taking a religious turn not unlike that of Eliot; while this interest clearly defines History of Religion and Eros, it is also apparent in the Socratic dialogue Mi & Lo, where Loys philosophy, like Platos, is informed by the human relationship to the divine. The religiosity of Loys late oeuvre does not mesh comfortably with the scabrous hijinks of earlier satirical fictions like The Stomach; nor does Loys faith sit easily with our presumptions about modernist secularism. But this facet of her writing has only recently begun to be addressed, and is part and parcel of a conversion to Christian Science that Loy enacted well before she started writing ( BM 117).

Next page