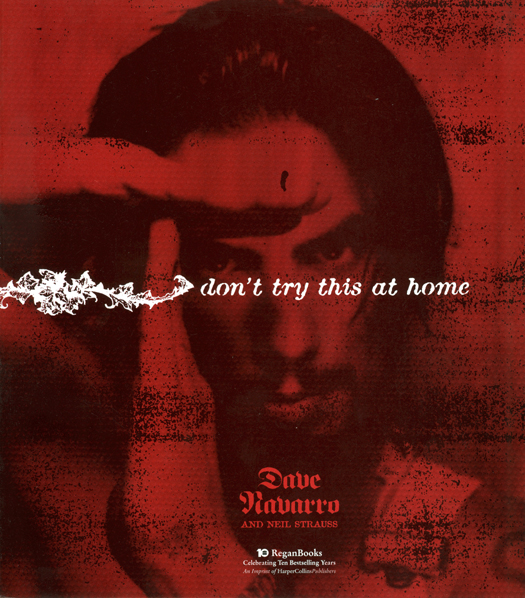

In memory of

Jen Syme and DArcy West

Contents

Do you know what to do when somebody shoots up too much?

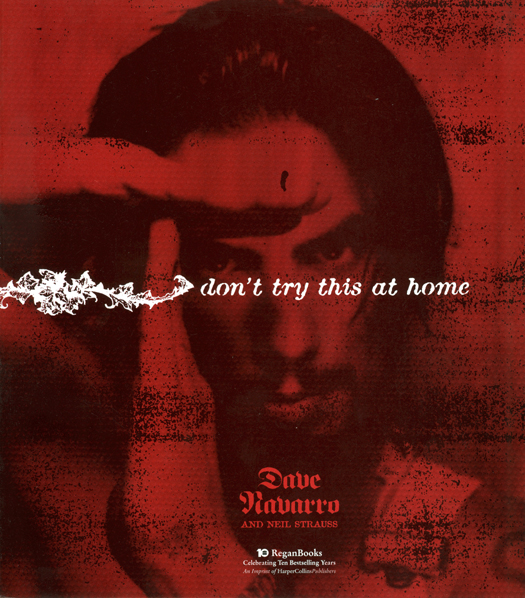

Thats the first question Dave Navarro asked as we began this collaboration on June 1, 1998, making it clear that I had more than a life story on my hands: I had a life. Not a series of past events filtered through the dirty grate of memory, but a heart that was still beating. To document the beating of that heart was the goal, and if the past was relevant at all, it was only as the blood that coursed through that heart and gave it a reason to beat. Or to not beat. Because at times, that heart didnt want to beat.

That night, Navarro showed me what he called his Spread movie. It began with a phone call to a rehab center. Navarro told the operator that he was in trouble and needed help badly; the operator said shed call back later. The rest of the movie was a series of scenes he had filmed to the accompaniment of his music. It centered around three images: a spoon in a bowl of Jell-O, symbolizing the nourishment of his past; a spoon with a rock of cocaine, symbolizing the nourishment of his present; and a picture of his mother, the bond that connected both spoons. In the movie, he shoots up with a picture of his mother in the background, an image all the more disturbing if you consider that Navarros mother was murdered by an ex-boyfriend, a man Navarro had grown to trust. Occasionally, the camera would pan to a computer screen, which displayed the phone number of his lawyer and directions on how to find a certain song in his CD changer.

The movie seemed disgusting not because of the images, but because of Navarros eagerness to exploit a tragedy for the sake of a self-aggrandizing art film. At least, thats what I thought until Navarro said it wasnt an art film. It was his will. The song in the CD changer, which he wanted played over and over at his funeral, was This Is How We Do It by Montell Jordan.

That was my checkout movie, he said. It was supposed to be a note of explanation before I ended it. I was going to take a bunch of pills afterward, because I thought it wouldnt be as ugly as being found with a needle in my arm and blood all over the place. I got the idea from Final Exit, which I always considered a how-to manual. But when I started editing the video, somehow it showed me there was something to live for, there was something else I could do creatively. I realized that because I was getting picky about certain scenes and wanted to reshoot parts. I guess I cared.

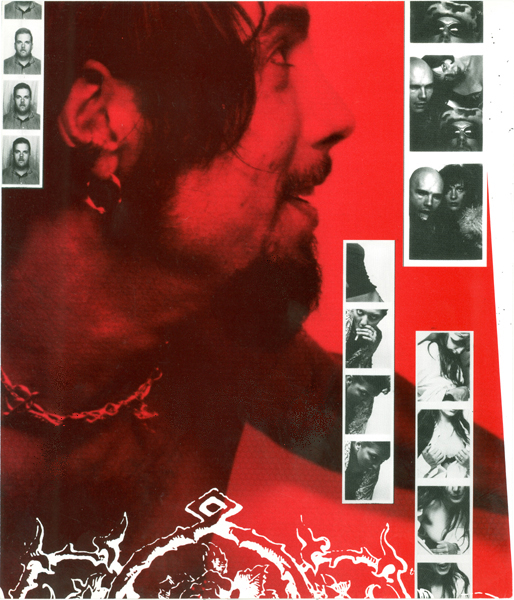

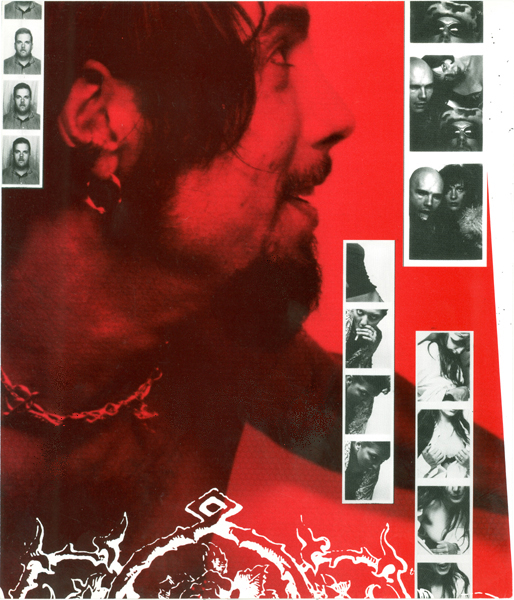

Navarro stood up and rolled thick black curtains across his picture window overlooking L.A. (I bought a house with a picture window so I could imagine myself pissing on L.A.), as if that would keep the sun from rising. And it did, at least for us and Mary, a statuesque, raven-haired drug dealer who sat mutely on the floor with her arms wrapped around her knees. A beautiful South Dakota girl too smart for her hometown, she moved to Los Angeles seeking a new life and somehow wound up selling drugs to people like Navarro, Leif Garrett, and Marilyn Manson. Sitting limply at her feet was her ladybug backpack and a needle dragon, a felt animal-shaped zipper bag containing syringes instead of the pencils for which it was intended.

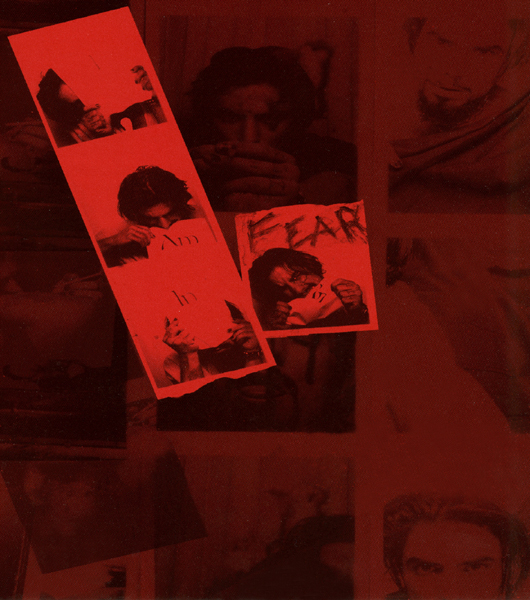

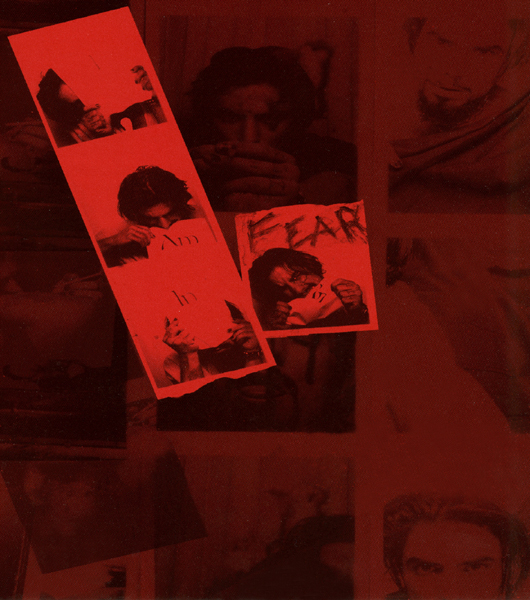

All does not seem well at Navarros Hollywood Hills home. But at the same time, things have never been better. Since a messy split with the Red Hot Chili Peppers and the suitably named Janes Addiction Relapse tour, Navarro has been in a strange transition. In the months leading up to June, everything changed for him. His career as a guitarist in two famous rock bands ended; he had a messy parting with the label that was going to release his solo project; he turned his back on the friends and relatives closest to him; he suffered a rough breakup with his girlfriend, Adria; he started shooting up coke and heroin again; and he bought a photo booth.

Socially artistically, and chemically, Navarro restructured his entire lifeor had it restructured for himwith the photo booth serving as a way of systematizing the friends, dealers, prostitutes, and strangers passing in and out of it. By the end of this yearlong book project, a process piece chronicling twelve months of his life in photo-booth strips, essays, and conversations, the outcome of these changes will become clear. This is a story that will either have a happy ending or a tragic one: there is no in-between.

Maybe Ill die and make the book a bestseller for you, Navarro said that first night. It would have been easy to laugh off the comment or think of it as a self-pitying plea designed to make the listener feel uncomfortable, but it was not a joke or a test. As he spoke, he tied off his left arm with an RCA cable and plunged a syringe into his arm, tapping the plunger as the phone rang. He picked it up, needle dangling from his skin like a cigarette from someones lips, and put the caller, Marilyn Mansons drug-addled bassist Twiggy Ramirez, on speakerphone. Twiggy had just snorted a fingernail-size line of Ketamine, a cat tranquilizer, and was freaking out. His walls and Star Wars toys were closing in on him, the red wine wasnt bringing him down, and he wanted to come over.

One of the biggest changes Navarro made in his life this month was in transforming his Hollywood Hills house into a cross between a crack den, an after-hours club, a halfway house, and Andy Warhols Factory. It became a fucked-up focal point for wretched freaks and glamorous stars to gather and discover that inside, the freaks feel like stars and the stars like freaks. The house is best summarized by the road sign perched one hundred feet uphill: DEAD END: NO TURNAROUND.

Next page