Submarines are designed to steal upon surface targets, their submerged, unseen presence giving them a distinct advantage over their unsuspecting prey. While underwater, subs are blind to each other. Their purpose is not to hunt enemy submarines.

This operations success is credited in newspaper articles, magazine features, television documentaries, and Internet sources as one of the more dramatic accomplishments of Project ULTRA, the British effort to crack the Nazi Enigma codebut those accounts are inaccurate, or just partly accurate, as are other details of U-864s mission that have been presented in popular media.

What is particularly unfortunate amid the blurring of fact has been historys complete omission of the crucial role of the Norwegian underground in the events that occurred in a remote stretch of the North Sea on February 9, 1945. The errors committed in previous accounts of U-864s missionand destructionmight present a tidy and linear narrative, but war is messy, and the actions of many who fought it can be obscured when squeezed into the time line of an hour-long television script or five-hundred-word newspaper article relying on that script for its information.

This book tells the story of U-864s mission as it really happened, and in doing so gives overdue credit to the forgotten heroes of Norway who helped end it.

1.

February 9, 1945

Kristoffer Karlsen had climbed the rocks in time to see the blast hurl a tall, white spout of water into the air about two miles from shore. The cold wind slicing through him, he watched it rise more than sixty-five feet above the chop in a vertical column, and then saw a thick jet of smoke follow it skyward.

Though only twelve years old, Kristoffer knew at once what he was witnessing as a long, dark shape broached the surface, rearing briefly into sight before it settled back into the depths. Decades would pass before his belief was officially confirmed, but he could not have been any surer than he was when it happened.

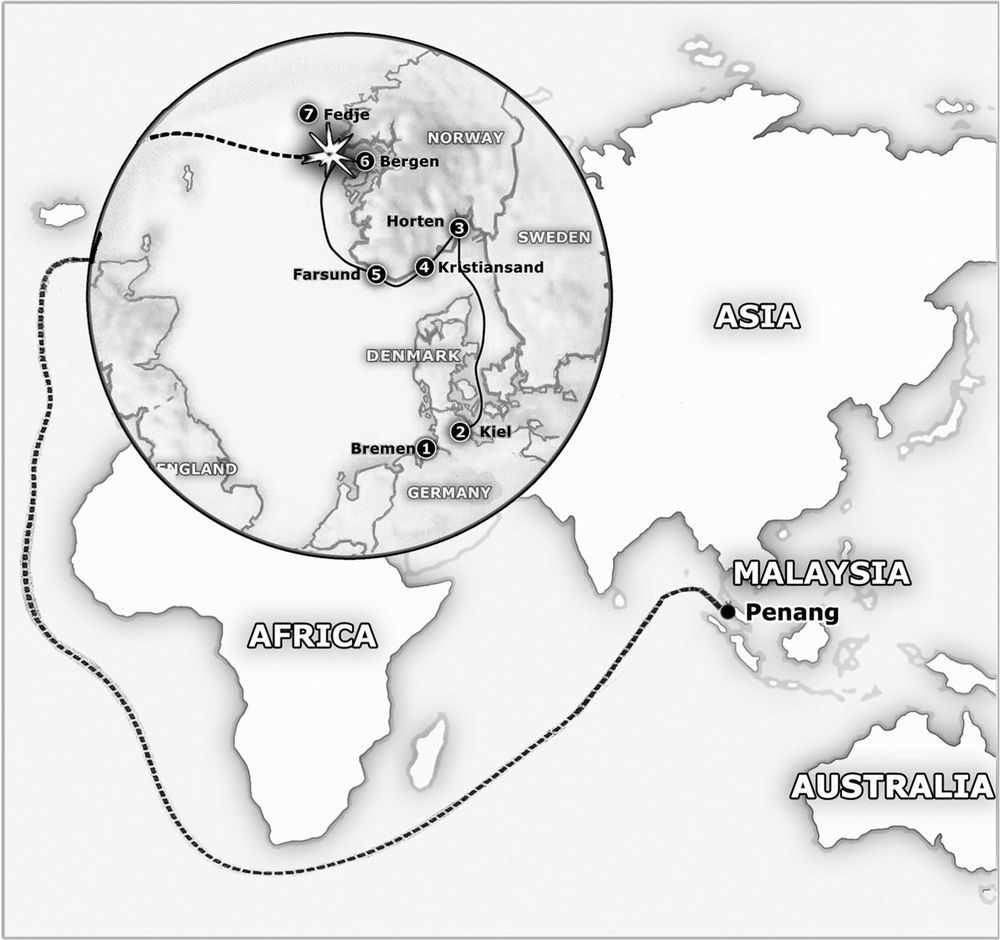

A windswept little island of less than five square miles, Fedje sat off the western coast of Norway in the North Sea, inhabited by several hundred fishermen, whalers, and their families, along with the scattered sheep and cattle in the modest pastures outside their cottages. The coastline was boulders and gravel; the interior, swamps, moors, and peat bogs; the surrounding ocean dotted with an archipelago of over a hundred bare, stony islets and humpbacked reefs. With timber for heating and cooking a scarcity, the islanders had discovered the value of harvesting the abundant peat as fuel; high in carbon, the spongy turf burned more efficiently than firewood. Beneath the sward, or outer layer, was the tarry black material that islanders would dig up with a hand spade, cut into strips or squares, and then dry for later use.

Kristoffer had been out gathering peat with his grandmother when he went up atop the bluff on the west side of the island, wanting to enjoy the view of the sea. He was not surprised to learn afterward that his fellow islanders had failed to notice the explosion; it was wartime , and they were under occupation, and things of that sort had in a sense become commonplace. The Germans had invaded the country when Kristoffer was just a boy of seven, garrisoning over three hundred soldiers here on an island whose population barely doubled their number. The occupiers had blown concrete bunkers and gun emplacements into the hillsides; they had thrown up barracks and target ranges on private land, fenced them off with barbed wire, and planted mines around them to keep out the families that had lived there; they even created a railway to haul granite blocks blasted from their quarries to the site where they had erected a radar tower in Vinappenthe islands highest point, 140 feet above sea level.

The smoke and noise, then, were nothing extraordinary or startling to the members of Fedjes tiny fishing community. But if they remained unaware of the event Kristoffer had observed, the garrisoned German soldiers had a very clear and immediate reaction. The boy noticed them break into hurried activity, sounding a general alarm and rushing to their bunkers and gun emplacements. With a sweeping view of the ocean from north to south, and their men on the alert for British naval and merchant convoys, they could not possibly have missed the explosion from their overlooks on the western shore.

Kristoffer Karlsen would never know what further action, if any, the incident prompted from the Germans. But in the weeks, months, and years afterward, the off shore submarine wreckage became widely known to the islanderswhether through Karlsen telling the story, or German soldiers interacting with the locals in the village pub, or local fishermen whod glimpsed pieces of the wreckage from their boats. There were persistent rumors of it carrying Nazi gold, atomic bomb components, even Hitlers last will and testament in its stowage areas. The stories long outlasted the war, as did the submarines secrets.

It was only in 2003 that the vessels presence and exact location was officially charted by the Royal Norwegian Navy, thanks again, in large part, to a Fedje inhabitants chance discovery.

2.

At first Karstein Kongestol was baffled and frustrated by the situation. Cast from his small fishing boat to a depth of five hundred feet, his net had gotten snagged on something large and heavy, caught so stubbornly that it thwarted his repeated attempts to pull it free. A strapping islander and professional fisherman, Karstein had good strength in his arms. But hed been about to give up and detach the lines.

As fate would have it, the net jerked loose on what would have been his last crack at recovering it. His exertions had left it in tatters , although he found his curiosity piqued while hauling it in over the keel. Tangled in its ragged strands was what appeared to be a tarnished, lichen-encrusted lump of brass about the size of a mans fist. But on closer inspection, Karstein realized the object was some sort of valve. Imprinted on the bottom of the fitting were measurements, serial numbers, and a German swastika.

When hed steered his cutter back to shore, Karstein brought the fitting into his small wooden boathouse, storing it away there with his line, gear, buckets, and tools.