Acknowledgements

In writing this book, I quickly came to realize how much I owe to other people: family, friends, colleagues and some sources who, because of the sensitivity of certain aspects of this book, must remain anonymous. To the latter group I am constrained to simply thanking you for having given me so much help.

To my wife Lorraine, I wish to say sorry for having caused you so much anxiety in 1982. To my two sons, Justin and James, I wish to say thank you for being such a tower of strength and support to your mother when she most needed it. To my daughter Kate I am most grateful for your patience and dedication in proofreading the manuscript.

I am particularly grateful to the following for reinforcing my own memory with their recollections, anecdotes, photographs and records from their flying logbooks and other sources: David Balchin, Alan Bennett, Simon Branch-Evans, John Cummins, Peter Imrie, Lyn Middleton, John Middleton, David Morgan, Nigel North, Bill Pollock and Simon Thornewill.

I would also like to express my appreciation to the following:

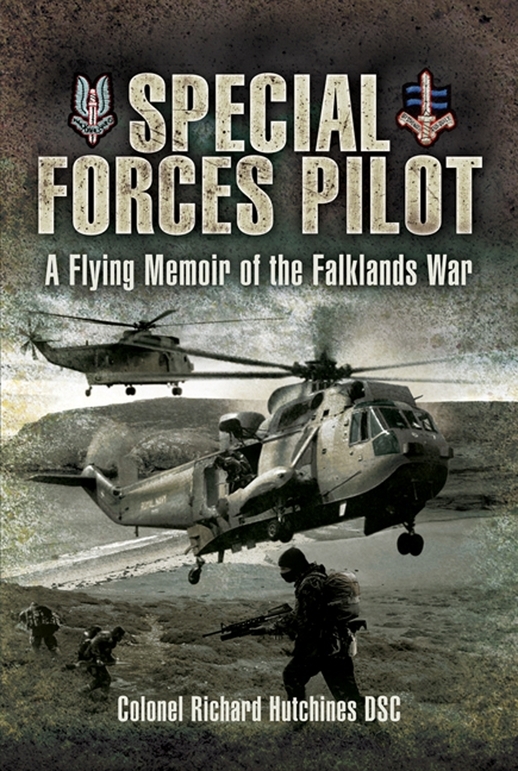

Edward Hamilton and Christine Cox for granting permission to reproduce the late John Hamiltons painting of the Pebble Island Raid on the jacket to this book.

The MoD, in particular Rear Admiral Ian Moncrief, for granting permission to reproduce Admiralty Charts. The charts at Maps 1, 3 and 4 are reproduced by permission of the Controller of Her Majestys Stationery Office and the UK Hydrographic Office.

The Press Association for granting permission to reproduce the photograph of my family during the Investiture at Buckingham Palace.

Professor Nigel West for granting permission to quote extracts from The Secret War for the Falklands .

Extracts from One Hundred Days by Sandy Woodward, 1992 are reprinted by permission of HarperCollins Publishers Ltd.

Epilogue

With 846 Squadrons programme as busy as ever, life at Yeovilton resumed a semblance of normality come the autumn. That was up to the moment when one morning, during the last week of October, I received a phone call from Colonel John St J. Grey, Colonel Operations, on the Staff of the Commandant General Royal Marines. Colonel Grey invited me to meet him in the MoD the following week, but could not discuss the purpose of my visit on the phone. How mysterious, I thought.

The following week I dutifully travelled to London and called on the Colonel who informed me that I was to receive a short briefing from an Air-Vice Marshal in preparation for returning to Chile at the invitation of the Chilean Government. Colonel Grey accompanied me to the meeting with the Air-Vice Marshal, an encounter which can best be summarized as businesslike and frosty. The Air-Vice Marshal wasted no time on pleasantries, but instead launched into a tirade criticizing the Royal Navys conduct of NVG flying operations during the Falklands War. He concluded by informing me that it was a role of the RAF to support Special Forces and not the Royal Navy, and that the RAF should have flown the NVG operations in support of Special Forces and not the Royal Navy. When I pointed out that two sets of NVG had been loaned to the crew of the one Chinook to have survived the attack on SS Atlantic Conveyor , and the helicopter promptly hit the surface of the sea whilst the crew were flying with goggles, Colonel Grey intervened and politely asked the Air-Vice Marshal to finish his briefing.

In a nutshell, President Reagan was planning a round of visits to Latin American countries to mend fences and build bridges after his governments support to the UK during the Falklands War. I was to return to Chile in November to locate and destroy all equipment that had been buried at our last location on top of the hill overlooking Punta Arenas. The Chilean Government was keen to pre-empt the possibility of any embarrassment that would arise should an inquisitive civilian happen to stumble across British military equipment in Punta Arenas at the time of President Reagans visit to Chile.

On Tuesday, 16 November I flew to Miami on a BA flight arriving early evening. Following an overnight stay in an airport hotel, I flew on a LanChile flight to Santiago via Lima, Peru, arriving late on the Wednesday evening. On arrival, I was met by Sid Edwards who briefed me on the programme for the remainder of my time in Chile. Early the next morning, we flew on a LanChile flight to Punta Arenas where we were met by two officers from Chilean Air Force Intelligence, one of whom introduced himself as Ernesto. We drove to a lay-by close to the Carabineros headquarters, where I had been six months earlier, where the vehicle was parked. The three of us then set off on foot to walk up the hill, retracing my steps from several months earlier. After thirty minutes we arrived on top of the hill and I quickly found the location where, on 25 May, I had buried the bergens containing spare clothing, sleeping bags, a tent and, most importantly, the fifty ampoules of diamorphine. Alas, someone had got there before us. It was readily apparent from the maturity of the growth of vegetation in the immediate area that the site had been discovered many weeks earlier, perhaps within a few days of Wiggy, Pete and me vacating the position at the end of May. There was no kit to be recovered and no diamorphine. Without further ado, my Chilean minders and I walked back down the hill, got into the car and drove to the home of Ernesto.

That evening my hosts treated Sid and me to an evening in a local fish restaurant where a good time was enjoyed by all. Later that night we returned to Ernestos home where I awoke during the early hours with severe stomach pains. It was not long before the contents of my stomach were down the loo and I spent the remainder of the night emptying the contents of my digestive system from both ends, sometimes simultaneously. Later that morning, somewhat the worse for wear, it was time to bid farewell to my hostess and travel to the airport to catch the flight to Santiago, a journey that I was dreading. I was accompanied on the flight by Ernesto. Once airborne, no sooner had the Captain switched off the seat belts sign, than I was occupying one of the lavatories, where I remained for the duration of the three-hour flight. Following our arrival in Santiago on the Friday afternoon, I was barely able to walk through severe dehydration. Ernesto arranged for a military car to collect us from the airport and I was driven immediately to the military hospital where I was diagnosed with acute food poisoning and admitted for a few hours, during which time intravenous drips were administered via both arms and legs simultaneously. Fully rehydrated, I was discharged later that night and was driven to an hotel in the centre of Santiago.

At 0900hrs on the Saturday morning, I was collected by car from the hotel and driven to the airport where I boarded a LanChile flight for the return journey to Miami, arriving at 1900hrs. There were no flights to London until Monday, 22 November so I spent the Sunday relaxing as best I could, nursing very tender insides. On the Monday I flew to London on a BA flight departing 1930hrs, arriving at Heathrow on the Tuesday morning at 0900hrs. Within a few hours I was back at my desk.

I was to reflect on my recent experiences over the next few days. The Falklands War had been an action-packed, short-lived and close-run adventure. The return visit to Chile had also been a short-lived adventure, characterized by mystery, excitement, disappointment, frustration and pain was this to be the norm for me from now on I wondered?

As the months turned into years, the interest of journalists in Operation Mikado gathered pace. From time to time I received phone calls from newspaper journalists and other writers asking me to reveal aspects of the operation, but I maintained my silence. It was not until 1996, with the publication of the Sunday Times article, that the story was placed in the public domain on the authority of the MoD. Whereas the account of events in Argentina, as briefed by the SAS to Nigel West, was a misrepresentation, the account of events in Argentina as written in this book is definitive.