Thank you for downloading this Simon & Schuster eBook.

Join our mailing list and get updates on new releases, deals, bonus content and other great books from Simon & Schuster.

C LICK H ERE T O S IGN U P

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

Contents

For Mary and Luke

List of Illustrations

ILLUSTRATIONS IN THE TEXT

PLATE SECTION

A Note on Quoting the Plays

Quotations from Shakespeares playswith the exception of King Lear are cited from David Bevington, ed., The Complete Works of Shakespeare, 6th ed. (New York, 2008). For King Lear I quote from Stanley Wellss edition, based on a text prepared by Gary Taylor (Oxford, 2000), that derives from the 1608 quarto and so is closer to what was staged in 1606 (and is divided into twenty-four scenes, rather than five acts). Like almost all recent editors, Bevington and Wells modernize Shakespeares spelling and punctuation; Ive done the same with the words of Shakespeares contemporaries throughout the book.

PROLOGUE

January 5, 1606

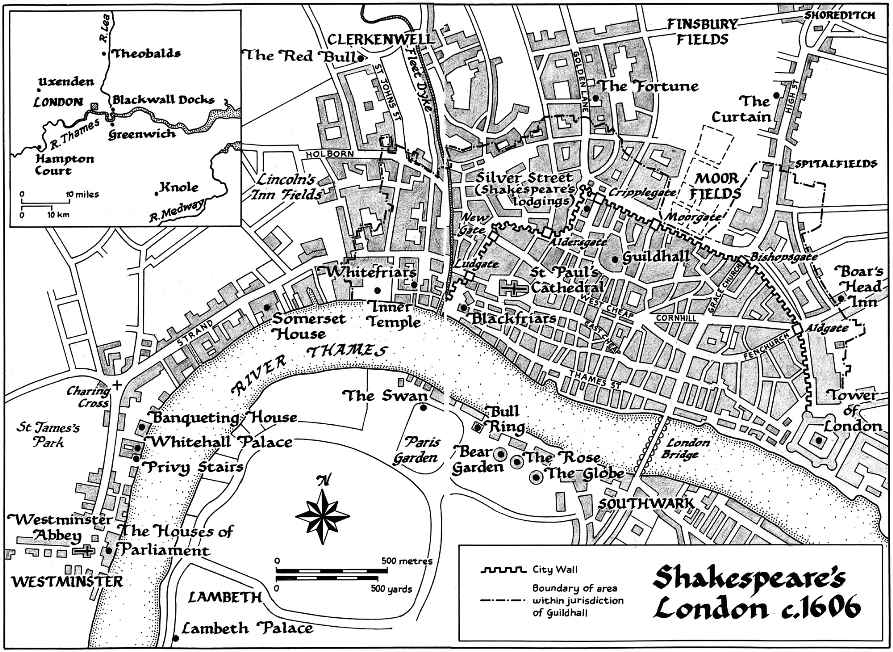

O n the evening of January 5, 1606, the first Sunday of the new year, six hundred or so of the nations elite made their way through Londons dark streets to the Banqueting House at Whitehall Palace. The route westward from the City, leading past Charing Cross and skirting St. Jamess Park, was for most of them a familiar one. Many had already visited Whitehall more than a half dozen times since Christmas, the third under King James, who had called for eighteen plays to be staged there this holiday season, ten of them by Shakespeares company. They took their places according to their status in the seats arranged on stepped scaffolds along three sides of the large hall, while the Lord Chamberlain, white staff in hand, ensured that no gate crashers were admitted nor anyone seated in an area above his or her proper station. King James himself sat centrally on a raised platform of state facing the stage, surrounded by his closest entourage, his every gesture scrutinized, rivaling the performers for the crowds attention.

This evenings entertainment was more eagerly anticipated than any play. They were gathered at the old Banqueting House to witness a dramatic form with which conventional tragedies and comedies now struggled to compete: a court masque. With their dazzling staging, elegant verse, gorgeous costumes, concert-quality music, and choreographed dancingoverseen by some of the most talented artists in the landmasques under the new king were beyond extravagant, costing an unbelievable sum of three thousand pounds or more for a single performance. To put that in perspective, it would cost the crown little more than a hundred pounds to stage all ten of the plays Shakespeares company performed at court this Christmas season.

The actors in this evenings masque, aside from a few professionals drawn from Shakespeares company, were prominent lordsand ladies too. The entertainment thus offered the added frisson of watching women perform, for while they were forbidden to appear on Londons public stages, where their parts were played by teenage boys, that restriction didnt apply to court masques. Those lucky enough to be admitted to the Banqueting House saw young noblewomen perform their parts in breathtaking outfits designed by Inigo Jones, bedecked in jewels (one onlooker reported that I think they hired and borrowed all the principal jewels and ropes of pearl both in court and city). For many of these women, including those who had commemorative paintings done of them wearing these costumes, this chance to perform in public would be one of the highlights of their highly constrained lives.

The building in which they performed was perhaps the only disappointment. Back in 1582, when the Duc dAlenon had come courting, Queen Elizabeth ordered that a temporary Banqueting House be constructed in time for his reception. From a distance the large building, a long square, 332 foot in measure about, looked imposing, constructed of stone blocks with mortared joints. But as visitors approached they would have seen that a trompe loeil painting disguised what was actually a flimsy structure, built of great wooden masts forty feet high covered with painted canvas. As the years passed, Elizabeth saw no reason to waste money replacing it with something more permanent, and by the time that James succeeded her, the temporary frame that had stood for a quarter century was in disrepair.

Shakespeare knew the old venue well and had played there fourteen months earlier on November 1, 1604, when his last Elizabethan tragedy, Othello , had had its court debut. Over the years he had performed often at Whitehall and would have recognized many of those in attendance. We can tell from the impact this masque had on his subsequent work that Shakespeare had secured for himself a place in the room that January evening. There probably wasnt a better vantage point for measuring the chasm between the self-congratulatory political fantasy enacted in the masque and the troubled national mood outside the grounds of Jamess palace. Insofar as most of his plays depict flawed rulers and their courts, he may have been as intent on observing the scene playing out before him as he was in viewing the masque itself.

The new king hated the old building; it was one more vestige of the Tudor past to be swept away. A few months after this masque was staged James commanded that it be pulled down and a more permanent strong and stately stone edifice, befitting a Stuart dynasty, be built on the site. In the short term, while there was little he could do about its rotting frame, James could at least replace Elizabeths unfashionable painted ceiling. She favored a floral and fruit design; he had it re-covered with a more stylish image of clouds in distemper.

King James was no less committed to repairing some of the political rot his predecessor had left behind, and this evenings masque was part of that effort. Five years had passed since Queen Elizabeth had put to death her one-time favorite, the charismatic and rebellious Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex. His execution still rankled Essexs devoted followers, and their further exclusion from power and patronage under James had left them bitter and alienated. Essex had left behind a young son, now fourteen, who bore his name and title, around whom they might rally. Essexs militant followers had to be neutralized in order to forestall division within the kingdom. But James couldnt simply restore them all to favor (as he had with the most prominent of them, the imprisoned Earl of Southampton), even if there were enough money, offices, and lands to do so, for that would unsettle the balance of favorites and factions at court. And he couldnt imprison or purge them all either. That left one solution: binding enemies together through an arranged marriage. James would play the royal matchmaker, marrying off Essexs son, now a ward of the state, to Frances Howard, the striking fifteen-year-old daughter of the powerful Earl of Suffolk, who had served on the commission that had sentenced Essex to death. That evenings masque, intended to celebrate their union, doubled as an overt pitch for the political union of England and Scotland, a marriage of the two kingdoms that James eagerly sought and knew that a wary Parliament would be debating later that month.