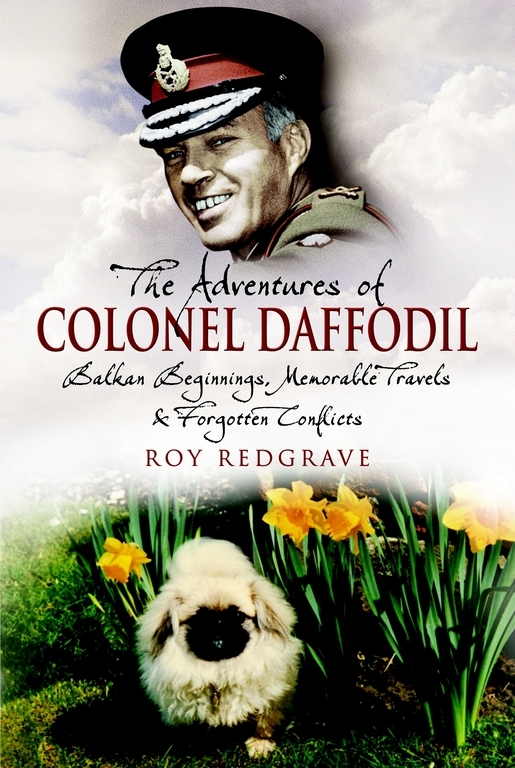

I am indebted to Douglas Liversidge, Commander Angus Erskine RN and Sir Alexander Glen, who have all died in recent years, for telling me about their experiences in the High Arctic.

I am grateful to Olav Farnes for his recollections and to Tom Hartman for his painstaking checking of Inuit and Romanian spellings and for the presentation of this book. I have been encouraged by the enthusiasm and sage advice of my publisher Brigadier Henry Wilson.

My heartfelt thanks for the memory of loana Hart, my sister, who checked the first six chapters before she died a few months ago. My constant solace throughout the years it has taken me to decide to conclude this book has been entirely thanks to the persuasion, patience and understanding shown by my wife, Valerie, to whom I dedicate this book.

AFTERTHOUGHTS

Sadly, there were no more Olgas to give my travels a touch of the unexpected. It was always the people I met who made each journey worthwhile. I soon discovered that in every community there was a man in a humble position of authority who carried great responsibilities and the need to make bold decisions, at least in the eyes of his village. It might be the village constable or the local fisherman who was expected to be the first to take his dog sledge to test the thickness of the freshly frozen ice. The villagers all relied on his judgement.

Sometimes they might call for help from the best hunter when their flocks of sheep were being ravaged by a rogue wolf or pack of wild dogs. It might be a frontier guard who has to decide whether to allow a smuggler whom he knows pass and then risk the sack, or to arrest him and fear for the safety of his family. He often has lonely decisions to take, which to him and the community he serves appear momentous, but to an outsider who does not know the implications seem to be quite straightforward.

I have faint memories of other adventures, for instance going to a theatre in Macao, China, to see a cultural dance. My wife, Valerie, was the only woman among a sea of Chinese males, all wearing dirty mackintoshes. The star of the show was a young lady from East Germany called Kiki Railroad, who did a striptease dance on a red motorbike inside a glass water tank to much clapping and excited chatter.

In North Cyprus at Kantara Castle in the Kyrenia Mountains I was showing a busload of tourists round when a gentleman had a heart attack. There was not a telephone or house in sight. Not wishing to alarm the passengers, the tour manager, Fiona Guertz, and I put him on the back seat between us and said that he was not feeling well. I told the driver of the ancient bus to get us off the mountain fast. He got the message. At every hairpin bend the body, for he was by now dead, slid off the bench. I jammed his legs behind the struts of the seat in front. Then we thought, what if rigor mortis sets in before we get to a village? To cut a long story short, we had to drive round Famagusta trying to get someone to take the body off us!

Other memorable journeys include Brazil with its purpose-built capital city, Brasilia. All government offices were protected by a moat and all buildings stood on concrete pillars to protect them from hostile crowds. No wonder people preferred to live in Rio and enjoy its fabulous beaches.

In Kyoto, Japan, in the spring when the blossom was out, I was directed to where I could spend a penny and tucked myself away in the corner of a long building. I was horrified to be joined by four giggling ladies who came and stood on either side of me. There was a forced landing in Cameroon, a close call with a hippo at Juja, a farm in Kenya, butterflies in Brunei, the gold museum in Bogota, Indian embroidery in Guatemala and albatross and tiny penguins in New Zealand. It has all been wonderful and unforgettable. Travel breaks down barriers. I am sure if Daffodil had lived she would still be running ahead of me.

Chapter 1

DANUBE DEBUT

My Romanian grandfather, Mihai Capsa, was aged twenty-one when, long before dawn on 22 February, 1866, he joined a group of officers who forced their way into the royal palace in Bucharest. There was no bloodshed and complete surprise was achieved. Not unexpectedly, they found their ruler in bed with a lady whose notoriety was such that he was obliged to sign a document of abdication which the intruders had thoughtfully brought with them. One wonders what on earth had been going on in the royal bedchamber that proved so unacceptable to the exasperated officials of the fledgling country.

Nevertheless, within a very short time Colonel Alexander Cuza was on his way to Giurgiu on the Danube with a small travelling escort of cavalry to make sure he caught the next steamship back to Germany.

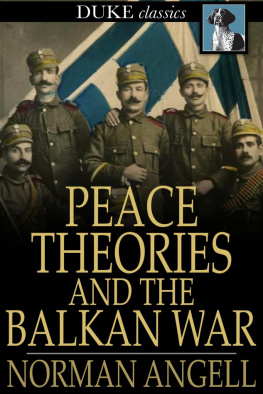

Six years earlier, in 1860, Moldavia and Wallachia had been granted independence within the Ottoman Empire. Both principalities chose the same man to be ruler and thus achieved an uncomplicated union to create a new Romania. Michael the Brave had tried to achieve this in 1600 and was sentenced to death by the Turks for daring to challenge their authority.

Colonel Alexander Cuza had been a popular choice to be the first ruler in 1859. Well aware of his own shortcomings, he warned his people, Gentlemen, I fear you will not be satisfied with me. Nevertheless, he started well. He removed all traces of feudalism, which still bound peasant farmers to their landlords. They were given plots of land based on the number of cattle they possessed. He secularized the Greek Orthodox monasteries which substantially increased the revenues to the State. This done, he decided to enjoy himself. He chose to ignore the corruption, favouritism, fraud and general ineptitude of his officials, which resulted in none of his reforms ever being successfully carried out. Very soon the new nation that had made such a promising start was heading towards economic disaster. Hence the dawn raid on the palace and his departure up the Danube.

Romania, then, was a difficult place to reach overland. There was no railway and the roads were awful. The only way to reach Bucharest from Central Europe in any comfort was down the River Danube. The Danube Steamship Company ( Donau Dampfschiffart Gesellschaft ) had been formed in 1829 by two British engineers.

There were many hazards, especially where the river breaks through the Carpathian Mountains at the Iron Gates. Negotiating the turbulent rapids, whirlpools and submerged rocks required ships captains with steady nerves. In winter the river remained frozen for up to two months. In summer the water level could drop so much that cargoes had to be off-loaded downstream to be collected later.

It is interesting to note that of the 1,190 vessels which travelled regularly between 1885 and 1895, the British owned 738. There were very few towns on the Romanian bank of the river because it flooded up to 15 miles inland, creating swamps in which millions of mosquitoes bred. The nearest landing point to Bucharest was Giurgiu where travellers gave up the comforts of the ship for a horsedrawn carriage which took two days to complete the journey.

Bucharest was founded by a legendary shepherd called Bucur who wandered across the plain with his family and flocks until he reached the River Dimbovitza where he set up camp. Bucur is said to have built a small church with a mushroom belfry. In so doing, he showed himself to be much more energetic than many of his successors. My Romanian great-grandfather was called Bucur or Bucus, a name supposed to have Albanian origins meaning Joy.