Contents

For the many thousands who have enjoyed

the reincarnated Muir

in Yosemite and elsewhere,

and most especially

for my loving and

much loved

Connie.

For all his lofty thoughts, for all his contributions and discoveries, I suspect that John Muir would long ago have faded into relative obscurity, save for his amazing adventures. Muir engaged wildness with perhaps more enthusiastic love and passionate courage than any other American before or after him. Usually alone, with little more than bread and tea for sustenance, often without coat or blanket, Muir eagerly explored the mountains of the American West. His written accounts of the events that befell him during his travels are astounding, amazing and almost unbelievable.

In fact, as an actor who regularly dramatizes many of these adventures, I am most often asked, Do you think Muir really did that? Well, I do. So did his contemporaries; no one who knew him or traveled with him doubted his word. Questioning Muirs veracity is commonplace enough nowadaysthe strength and stamina required to undertake these adventures suggest to many exaggeration, and to some, outright fabrication. My years of research suggest, however, that Muir was not only truthful in his writing, but in some instances quite modest.

Given the sheer quantity of Muirs work, remarkably little of it involves personal narrative. Much is descriptive commentary common to travelogues of the day (though generally of much better quality), some is scientific study and opinion, and a good deal is general sermonizing about the healthful effect of engaging wildness. Muir was often hounded by editors and friends to write more of his adventures and less of everything else, but he was reluctant to do so, confiding in his journals that he preferred to be a sort of prism, a flake of glass through which the light passes.

Except for the scootchers of his childhood (the games of daring that he and the other children enjoyed), Muir never seemed to seek adventure for adventures sake. His rationale was constantcuriosity and study were what motivated him, and wonder, exhilaration and learning were the rewards. Examples abound. He confronted and charged a large bear, hoping to make it bolt so that he could study his gait in running; eager to see as many avalanches as possible, he was caught up in one; tossed violently about the Yosemite Valley floor during Californias biggest earthquake, he was sure he was going to learn something; and anxious to learn more of this curious hill, he climbed a 500-foot wall of ice beneath the great Yosemite Fall.

The risks were real, but measured with the eye of a true mountaineer. Accidents in the mountains, he wrote, are less common than in the lowlands, and these mountain mansions are decent, delightful, even divine, places to die in, compared with the doleful chambers of civilization. Few places in this world are more dangerous than home. Fear not, therefore, to try the mountain-passes. They will kill care, save you from deadly apathy, set you free, and call forth every faculty into vigorous, enthusiastic action.

The Wild Muir was conceived as a book offering only wilderness adventures in which Muirs life or limb was threatened. When the final selections had been made, however, not all of the stories satisfied the original criteria. A purist, knowing of Muirs rugged constitution and his skill and ease in the out-of-doors, might consider it misleading to include the famous tree ride. His feelings were certainly those of sheer delight, not fear or threat. And three of these episodeshis brush with death at the bottom of the well, the industrial accident that nearly blinded him in Indianapolis, and the fever encountered in Floridawould be more properly labelled mis-adventures.

In all, twenty-two extraordinary, death-defying stories are included here. Written in his own words, they begin in childhood and continue chronologically through Muirs fifty-second year. The accounts all share Muirs zest for living and for everything that he encountered, and reflect some of his best and most engaging writing. The Victorian flourish and sense of leisure common to much of his prose are notably absent from this collection.

Besides Muirs writings, two other accounts supporting and amplifying Muirs versions of events are included in this volume. The first, part of a government report describing Muirs return from the violent storm on Mount Shasta, has never before been published (to the best of my knowledge). It provides several details of his suffering that Muir either neglected to mention or found unimportant. The other, S. Hall Youngs wonderful account of the rescue on Glenora Peak, gives us a sharply observed view of Muir as the vigorous mountaineer. It comes from Youngs Alaska Days with John Muir, and makes a fine counterpoint to Muirs version of the same episode.

The real purpose of The Wild Muir, however, is not to provide biography, to answer or raise questions, to fill in historical gaps, or to add to the endless conjecture about the true character of John Muir (though it does all of these things to some degree). It is simply to provide the reader a rousing good time. Twenty-two rousing good times. May you enjoy the adventure!

Lee Stetson

El Portal, California

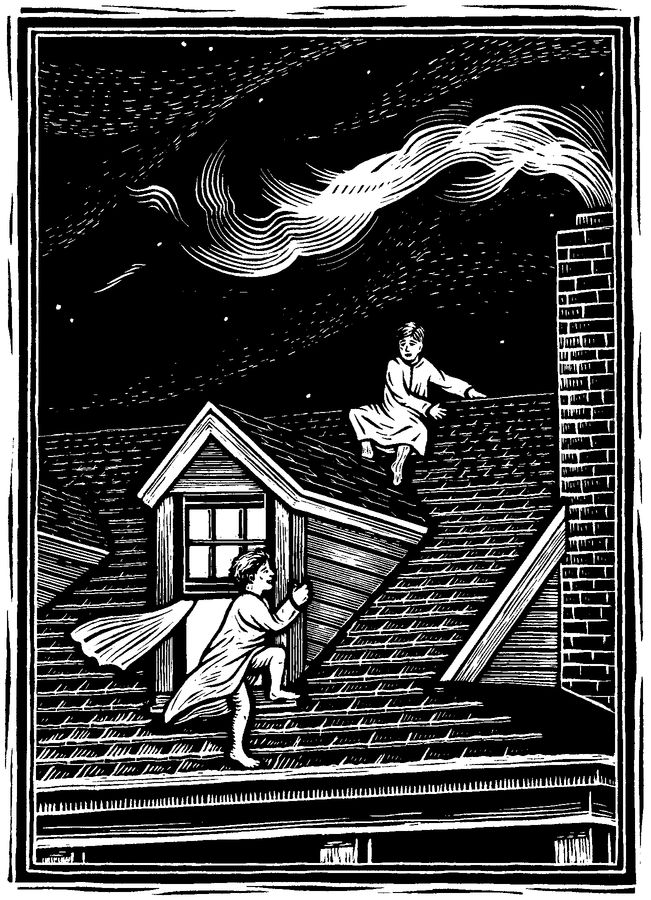

Born in Scotland on April 21, 1838, John Muir made early excursions into life- and limb-endangering activities that were undoubtedly typical of any high-spirited boy in the small town of Dunbar, on the North Sea. Muir called these games of daring scootchers. From The Story of My Boyhood and Youth comes this account of the future mountaineers first ascents, and of his first rescue of a fellow adventurer.

While Muir is still relatively unknown in Scotland, the East Lothian District Council in Dunbar has honored its native son; his early seashore playground has been preserved as the John Muir Country Park, and the attic of the Muir home has been set aside as a museum. Even more appropriately, in 1984 the John Muir Trust was established to acquire wild lands in Britain.

WHEN I WAS A BOY IN SCOTLAND I was fond of everything that was wild, and all my life Ive been growing fonder and fonder of wild places and wild creatures. Fortunately around my native town of Dunbar, by the stormy North Sea, there was no lack of wildness, though most of the land lay in smooth cultivation. With red-blooded playmates, wild as myself, I loved to wander in the fields to hear the birds sing, and along the seashore to gaze and wonder at the shells and seaweeds, eels and crabs in the pools among the rocks when the tide was low; and best of all to watch the waves in awful storms thundering on the black headlands and craggy ruins of the old Dunbar Castle when the sea and the sky, the waves and the clouds, were mingled together as one.

One of our best playgrounds was the famous old Dunbar Castle, to which King Edward fled after his defeat at Bannockburn. It was built more than a thousand years ago, and though we knew little of its history, we had heard many mysterious stories of the battles fought about its walls, and firmly believed that every bone we found in the ruins belonged to an ancient warrior. We tried to see who could climb highest on the crumbling peaks and crags, and took chances that no cautious mountaineer would try. That I did not fall and finish my rock-scrambling in those adventurous boyhood days seems now a reasonable wonder.