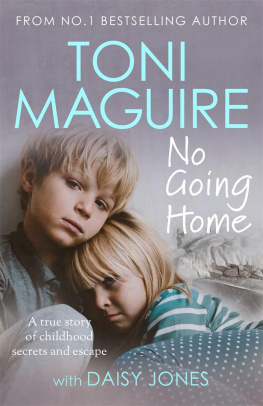

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

To our agent, Jennifer Di Chiara, who believed in us from the very beginning.

To our publisher, Rowman & Littlefield/Taylor Trade, editor Rick Rinehart, Jessica Kastner, Meredith Dias, Sara Given, Evan Helmlinger, and the rest of the Taylor staff, who saw merit in our work and have given this fledgling team their full help and support.

To Judy Donaldson, who lent her keen editing skills during the early stages.

To Jamie Blaine, who advised and encouraged us through his own experiences as a published writer.

To TEAM DAISY: Jane Tennille, Frank Engs, Marie Cranmer, and Michael Donaldson, all of whom have given their love and support throughout this entire project (and who have given us many laughs too).

And to my sisters: Jane, Louisa, and Melissa, who helped sharpen my focus when some of my memories were a bit fuzzy around the edges.

CHAPTER 1

Montgomery, Alabama, 1946

THE HUGE STEEL WHEELBARROW CRASHED DOWN ON MY TINY index finger and nearly severed it at the joint. I lay on the floor of our neighbors garage as my friends looked on in horror. Only seconds before we had been playing an innocent, silly game: We were running in and out of the narrow confines of the garage, chasing each other and laughing, when I slipped and knocked over the wheelbarrow. It crushed my finger to a bloody pulp.

What happened next is pretty much a blurred mix of my friends mother hurrying to my side, being rushed to the hospital with what was left of my finger plunged into a glass of ice and water, and then being in the glaring light of an examination room. When the shock subsided, the pain took over. But what was almost worse than the pain was seeing the worried faces of my parents as they huddled by my bed, talking with the doctors. I knew that if the adults were this concerned, the accident must have been serious.

Despite the limits of reconstructive surgery in the 1940s, the doctors at our Montgomery hospital did everything they could to save my finger. But the end of my right index finger eventually succumbed to gangrene and had to be amputated. Being only five years old, I couldnt understand why the bandage on my index finger was shorter than the other fingers on my hand. When the doctors came in to examine it and change the bandages, I would always look away. Finally, I summoned up the courage to ask my parents why my index finger was shorter than the rest. With tears in their eyes, they gently explained what had happened.

I realize that many people would not think an incident like this was so terribly tragic. Children have accidents all the time many far worseand my life was never in danger. But even at such a young age, I had already begun to show promise of having musical talent, especially on the piano. Our family thrived on musicparticularly my fatherand they loved nurturing my growing passion for it. What would this accidentthe partial loss of a fingerdo to my budding music capability?

Determined to make the best of the situation, Mother and Daddy enlisted the services of a renowned New Orleans plastic surgeon, Dr. Neil Owen, to attempt to reconstruct my finger. We would make the three-hundred-mile drive down to New Orleans from Montgomery for what would end up being thirteen surgeries by Dr. Owen over several years. Those surgical procedures would prove to be long, painful ones in many ways. Ether, the primary anesthesia used for surgery in the 1940s, made me violently ill with nausea and vomiting when I woke up from a procedure. A piece of bone was removed from my hip to replace the finger bone that had been lost, and in order to encourage new skin tissue growth over the transplanted bone, my finger was sewn to an incision in my stomach for six weeks.

I have a photo that Daddy took of me during this phase. Im smiling up at the camera from my hospital bed with my arm bandaged tightly to my waist to keep the finger in place where it is stitched to my stomach. Captured forever through the lens is Daddys love and concern for his firstborn child and his determination to do whatever was needed to make things rightno matter the cost. Years later I realized that the numerous surgeries must have cost my parents an enormous amount of money money that we probably didnt have. And later, when financial ruin finally caught up to our family, I felt guilty that the expenses from my accident had most likely contributed to it.

I experienced a tremendous amount of shame in the earlier stages of the reconstruction process when the finger still looked like a misshapen blob of fat and skin. It caused my classmates to shrink away in disgust, and a few even took it upon themselves to helpfully let me know my maimed finger was ugly. In response, I began to craft a skill that I perfected throughout the rest of my life: hiding my finger. I learned to look people straight in the eye and give them a big, dazzling smile. After all, I reasoned, if they only looked at my face they wouldnt notice the finger!

Thinking back, this smoke-and-mirrors behavior probably benefited me later in life when I became a performer, because I learned early how to divert attention to the most positive parts of myself. Through those thirteen surgeries, Dr. Owen was able to shape my index finger into something that looked less ugly, but it never again was a normal finger. I successfully hid this flaw from almost everyone for the rest of my life; I wore a stick-on nail during TV and concert appearances and deftly held my hand in certain ways so that it wasnt noticeable. Even some people who were very close to me never knew about it, or if they did, they never mentioned it. It was a secret that I carried with me everywhere, and I would know immediately if someone happened to look at my hand and notice something was wrong.

I was almost finished with the reconstructive surgeries when Mother took me for my first piano lesson with Miss Lilly Byron Gill. Miss Gill was a kind and gracious lady in her sixties who, in her youth, had studied with the famed composer and pianist Ignacy Paderewski. She taught her students in her Victorian-era house with long velvet drapes, sparkling chandeliers, and elaborate carved furniture, all of which whispered of faded grandeur from another time. Nervously, I showed my stunted finger to Miss Gill, worried about how she would react. To my relief she was completely undaunted and welcomed me as a piano student with open arms.

I wonder what would have happened if, instead of believing that I could overcome this slight handicap, Miss Gill had looked at my misshapen finger and told my parents to save their moneythat Id never be able play piano. If she had, my life would have been very different.

For years Miss Gill treated me as any other promising student and never, over the many years I studied with her, made me feel any less capable than if Id had ten perfectly formed fingers. Under her tutelage, I grew into a very good classical pianist, knowing how to make my maimed finger work so that it didnt hamper my ability to play. I loved playing music for people, but I still never wanted them to see that the hands creating it were less than perfect.

In many ways, Montgomery, Alabama, still looks the same as it did when I lived there in the 1940s and 50s. Majestic magnolia trees still tower over the sidewalks in the neighborhood where we lived, scenting the air with their sweet, heady perfume; and just as they did decades ago, neatly trimmed azalea hedges continue to bank the foundations of lovely old homes. Our house on Felder Avenue looks so unchanged that I almost expect to see the front door fly open and me or my sisters scramble down the steps on our way to a lesson or to meet friends at the park.

But the Montgomery where I grew up was still clinging to the past; it was beaten, yes, but still defiant. Steadfast in old southern customs, the city was charged with racial tension, and it turned a deaf ear to the prophetic whisper of the civil rights movement only a decade away. Segregation ruled almost every aspect of life, from schools to hospitals and even bathrooms and water fountains. Although I didnt understand it at the time and accepted it as just the way things were, I was always uncomfortable with segregation. My family would never utter a racial slur in public or private, and my sisters and I were taught to treat everyone, including our household help who were mostly black, with the same respect regardless of color. But even as a child, I couldnt help but notice the stark polarity between my communitys black and white residents.