Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the following friends and colleagues who assisted with sources of information: Andrej Angrick, Rainer Frbe, Peter Klein, Dieter Pohl, Ian Whittaker and Michael Wildt. For providing some of the illustrations, thanks also go to Michael Miller, Marc Rikmanspoel, Ian Sayer and, especially, Max Williams. We are also indebted to the British Armys Medical Services Museum at Aldershot, for allowing us to use the photograph of Himmlers death mask.

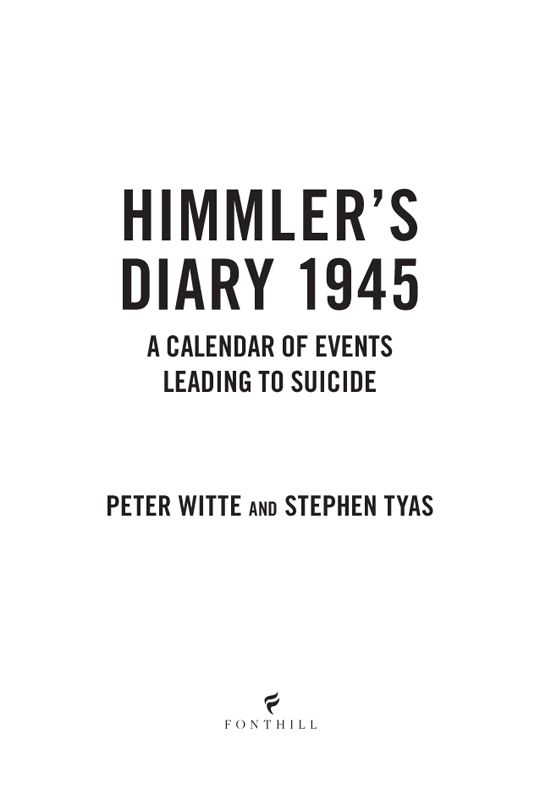

Fonthill Media Limited

Fonthill Media LLC

www.fonthillmedia.com

First published in the United Kingdom and United States of America 2014

Copyright Peter Witte and Stephen Tyas 2014

ISBN 978-1-78155-257-5

The right of Peter Witte and Stephen Tyas to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission in writing from Fonthill Media Limited

Typeset in 10pt on 12pt Minion Pro

Printed and bound in England

Connect with us

facebook.com/fonthillmedia facebook.com/fonthillmedia |  twitter.com/fonthillmedia twitter.com/fonthillmedia |

CONTENTS

Methodology and Sources

Methodology and Terminology

In presenting this research we have employed a three-fold methodological approach. First, there is a statement about the military situation over which Reichsfhrer-SS Himmler had no control. On some days there were no changes in the general military situation and therefore when this is the case these statements are omitted. Secondly, we made extensive use of Himmlers own desk diary in which he noted his meetings and appointments. These are handwritten entries by Himmler and can therefore be treated as entirely accurate. Unfortunately with the quickening pace of Allied armies advancing across Germany, Himmler made his last entry on 14 March 1945 before sending his diary to safety at his home in southern Germany. Lastly we have noted Events which are statements from various sources which involve actions and activities that included Himmler. Primarily these are from similar wartime diaries (Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels and Nazi Party leader Martin Bormann who also acted as Hitlers secretary), early post-war interrogations of Himmlers personal staff including his adjutants (Werner Grothmann and Heinz Macher) and the later memoirs and biographies of Nazi leaders and others who met Himmler during 1945.

In comparing and contrasting the widely different sources there is rarely any dispute between the timings and occurrences taking place. Where dates and times are obviously wrong, we have pointed this out. The timetable of events leading up to Himmlers death from the time of his capture has been re-constructed from British army sources.

Any publication involving non-English sources is fraught with language pitfalls and difficulties. To avoid making this terminology even more difficult we have maintained throughout a certain amount of German terms that are self-explanatory. For instance, Reichsfhrer-SS has no pertinent or correct English term and therefore we have maintained the original German term. To complicate matters Reichsfhrer-SS was abbreviated in different ways by individuals whose works we have quoted; thus we have RFSS, RF-SS, RfSS, Rf.SS and Rf-SS and all mean Reichsfhrer-SS. Rather than change the quotations we decided to keep to historical accuracy of the quoted work.

Similarly many works translated from German into English appear to have created their own literary terminology. Typically this occurs with the German word fhrer when used as a suffix, and seen translated as a capitalized noun Fuhrer (quoted with and without umlaut) when attached to someones SS-rank. Throughout we have quoted whatever has been

used.

This brings us to the German use of the Fhrer as an individual. It was common parlance among Germans alikefrom the man in the street to Heinrich Himmlerthat their shared use of the Fhrer always meant Adolf Hitler. The diaries of Himmler, Goebbels and Bormann all mention meetings with the Fhrer and no other information was necessary to indicate this meant Hitler. We have endeavoured to keep to correct names where possible. It is Joseph Goebbels and not Josef Goebbels, it is Adolf Hitler and not Adolph Hitler.

All SS ranks have no literal English translation, SS-Sturmbannfhrer may translate as SS Storm Troop Leader but its more precise equivalent is SS-Major. A list of SS ranks and their typical recognizable equivalents is included at the end. Similarly a list of abbreviations is also included.

The Sources for this Work

The primary sources we have used in writing this book are freely available in archives in Germany, Britain and the USA. Some were declassified decades ago; some more recently. For the first time, we have brought them together in a coherent chronology of events. In common with all government ministers, Heinrich Himmler found his life in government was not always his own and therefore there was a need to regulate his life through his desk diary. There are many diaries by Himmler that have proved invaluable to historians when documenting his life from the early days through to 1945, though the last entry is 14 March 1945. The diary entries quoted are little more than lines on a page with his occasional mistakes. For historians they show where Himmler was and, just as importantly, who he was with. A combination of times and people can establish why. Himmler regarded his diaries as part of his archive and for security reasons he had them sent south to Bavaria where they were lodged at his home in Gmund on the Tegernsee. Discovered when US troops searched the house after the war, they were recovered as part of the American Captured German records programme. In the 1950s, these records were returned to the West German government and placed in the Federal German Archives (Bundesarchiv). These original paper diaries of Heinrich Himmler are today lodged in the archives at Berlin-Lichterfelde.

The second and no less unique primary source we have used are the German police decrypts held at the National Archives at Kew (London). These decrypts are the only remaining record of German messages from the 1945 period still in existence, the originals having been either destroyed by air-raid damage or purposely burned at the time. Because British and American air raids on German cities and installations destroyed, among other things, the communications infrastructure that enabled teleprinter operations, the SS and police became reliant on radio operations capable of being intercepted in the ether. British wireless operators intercepted thousands of German messages and this particular stream of German police decrypts, deciphered at Bletchley Park, have proved extremely useful in tracking Himmlers movements and orders sent by radio. These German radio messages were originally declassified in 1997; a second series of separate German radio messages assembled by Britains Secret Intelligence Service (MI6) were declassified several years later along with another unique set of deciphered radio messages entitled Decrypts of Intercepted Diplomatic Communications. These diplomatic messages have a value in showing how Hitler and Himmler varied their responses to different foreign audiences; for example, we have quoted examples of Chinese and Japanese diplomatic messages that reveal information not provided by German sources.

facebook.com/fonthillmedia

facebook.com/fonthillmedia twitter.com/fonthillmedia

twitter.com/fonthillmedia