For Caroline, Julia, Victoria, Max,

Gemma and Nicholas

First published in Great Britain in 2009

By Pen and Sword Aviation

an imprint of

Pen and Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Alan White, 2009

ISBN 978 1 84884 021 8

ISBN 978 1 78303 672 1

The right of Alan White to be identified as the author of this work

has been asserted by him in accordance with the

Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted

in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying,

recording or by any information storage and retrieval

system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Printed and bound in England

by Biddles

Pen and Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of

Pen and Sword Aviation, Pen and Sword Maritime, Pen and Sword

Military, Wharncliffe Local History, Pen and Sword Select,

Pen and Sword Military Classics and Leo Cooper.

For a complete list of Pen and Sword titles please contact

Pen and Sword Books Limited

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Contents

Preface

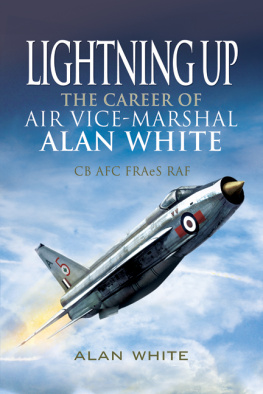

T his book is not an autobiography. I did not set out to write one. It is simply a record of a career in the Royal Air Force of a pilot who happened to be fortunate enough to fly fighter aircraft, and survive an occasional brush with Lady Luck.

I was not destined to fire my guns, having been too late for the Korean War and too old for the Falklands, and involved with little in between other than with some aspects of the Cold War and with a couple of minor dust-ups in the Far East. There was a time when I would have welcomed an opportunity to engage in aerial conflict. But one grows wiser with experience and time, and that foolishness passes.

I retain the greatest admiration for those who did and do find themselves flying in hostile skies, often with the odds stacked against them. Their courage humbles those who, like me, merely flew.

Acknowledgements

I am greatly indebted to my good friend Don McClen for encouraging me to write this book and for continuing to do so after he had ploughed through my first draft. His candid criticisms and helpful suggestions provided the essential catalysts for its successful completion.

I should also like to record and acknowledge the considerable help I have had in quite a variety of ways, from the confirmation of some of my hazy recollections, to the provision of facts, the sourcing of photographs, and the drawing of maps. The following acquaintances and friends all have my gratitude:

Hugh Alexander, National Archives, Kew

Peter Biddiscombe, old pal on 247 Squadron

Richard Calvert, friend and former squadron commander

Sebastian Cox, Head of Historical Branch (RAF)

Bill Duffin Hon Sec of the Independent Researchers Association

Paul Jackson FRAeS, Editor in Chief, Janes All the Worlds Aircraft

Norman Roberson, Honorary Secretary, 20 Squadron Association

Henry Roberts, amateur cartographer

Mick Rogers, Honorary Secretary 247 Squadron Association

Stewart Scott, author

Jerry Seavers, friend since 20 Squadron days

Eunice Wilson Archivist to 247 (F) Squadron Association

C HAPTER O NE

Just Out for a Spin

S itting on the top-deck of a Belfast City bus one miserably wet afternoon in January 1953, peering through its condensation-steamed windows, I found myself wondering what the hell I thought I was doing. I was on my way to Sydenham, now Belfast City Airport, to have my first experience of flying my familiarisation trip with Queens University Air Squadron. The rain was pelting down. The heavy dark cloud looked menacingly low. It had all been so totally different a few days earlier when I, and several other undergraduate would-be aviators, had spent a happy afternoon meeting the squadron instructors, having an introductory briefing, and being shown over the aircraft on which we were to be taught to fly. The prospect of flying had then been very appealing. In the present conditions it had no attraction at all and I seriously hoped that my trip would be cancelled.

About an hour and a half later, worrying weather notwithstanding, I was briefed and kitted out. I had fur-lined boots on my feet, a leather flying helmet and goggles on my head, and I had been handed a Mae West a bulky yellow flotation jacket to put on. I had been supervised as I trussed myself tightly into the harness of a parachute-pack shaped to fit in the aircraft seat and, with that pack swinging awkwardly below and behind me, I shambled out from the dry comfort of the squadrons accommodation to one of its four Chipmunks.

Climbing cumbrously into the front cockpit I was somewhat relieved to see that the rain was slackening and that the gloom was lightening away to the west but at that moment even a totally cloudless sky might not have dispelled the apprehension I felt about going up in this mini-machine whose cockpit hardly fitted me and which, besides, smelled slightly of sick.

Oddly, although I had been impressed by an older cousin who had come to spend a few days with my parents in the mid-1940s, proudly displaying Flying Officers tapes and pilots wings on his uniform, I cant recall feeling any great urge to follow in his footsteps. At school I had been fired with the idea of making a career in the Army but I had been armlocked by my father into deferring that ambition in favour of reading for a degree; he had even set me up with a meeting at the home of a friend of his, a professor at Queens, whose task was clearly to persuade me that a university education would be a much better bet than an immediate plunge into a military career.

While it would be wrong to say that I had had no interest in aeroplanes or in flying, I had never really given any thought to the possibility of getting airborne. My interests were elsewhere and, the moment I was old enough, I had joined the Territorial Army. The idea of the University Air Squadron (UAS) came three years later and owed more to the persuasive patter of a friend than to a burning desire on my part to learn to fly. And I doubt that his enthusiasm was initially any greater than mine as his principal argument for attempting to join was that: They have a great Mess and its open on a Saturday night long after the pubs in Belfast close.

UASs were set up the first at Cambridge in 1925 and anyone applying to join had to display both the aptitude to cope with flying lessons and the qualities that the RAF was seeking in its own recruits. We thus found that joining wasnt simply a matter of presenting ourselves as keen applicants for membership of a university club.

The first hurdle to acceptance was the medical examination, a fairly lengthy affair that covered everything from the history of our health, through its current state, to possible future infirmity. During the course of it I was asked if I ever got sick in cars or on buses and this gave me a momentary twinge of concern; I had been sick every time I got into a car when I was a child, but I didnt volunteer this last, hopefully irrelevant, piece of information as I had long since grown out of the tendency. Besides, as rough seas and boats didnt bother me I reasoned, optimistically, that aircraft would be unlikely to do so either. Happily, we were both pronounced fit and able to see and hear to the required standards.

The next hurdle was the Aptitude Test. This required the would-be aviator rapidly to interpret a series of diagrams and photographs briefly displayed to him. The diagrams, designed to test the applicants ability to solve general mechanical and mathematical problems, were in the format of a standard Intelligence Test. The photographs, which showed the standard flight instrument panels of RAF aircraft doing just about everything except flying straight and level, focussed the testing process more precisely. I had no idea how I scored on the Intelligence Test but I was relieved, and indeed smugly pleased, to find that I could read the instrument panels without difficulty.

Next page