First published in Great Britain 2003 by

LEO COOPER

an imprint of Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley, S. Yorkshire, S70 2AS

Copyright 2003 by Sydney Hudson

ISBN 0 85052 947 6

PRINT ISBN: 9780850529470

PDF ISBN: 9781783377664

EPUB ISBN: 9781783379866

PRC ISBN: 9781783379668

A CIP record for this book is available from The British Library

Typeset in Meridien by

Phoenix Typesetting, Burley-in-Wharfedale, West Yorkshire.

Printed by

CPI UK

For the morning will come. Brightly will it shine on the brave and true, kindly upon all who suffer for the cause, glorious upon the tombs of heroes. Thus will shine the dawn.

From Winston Churchills Speech

to the French Nation, 21 October 1940.

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

This book is a personal account of various events leading up to the Second World War, others which occurred during the war, together with a number of incidents which took place after the war but which had a connection with it.

The reader may well ask why I have waited for more than half a century to relate my story. I can only explain that I was involved in various matters totally unconnected with anything that happened during the war and simply never got round to something in the nature of an autobiography. It is only quite recently that I have had sufficient time on my hands. It also seems a pity that some rather interesting events should go untold. Though it is probably the case that my memory of these distant events has necessarily faded, it may also be that I have been able to judge different happenings in a better perspective than if I had been telling my story nearer to the time they took place.

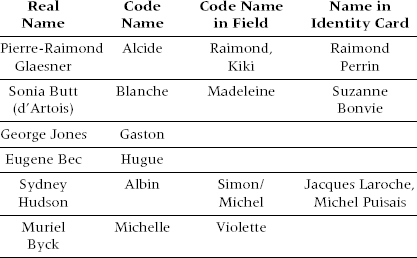

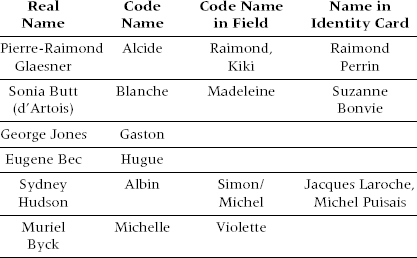

GUIDE TO CODE NAMES AND ALIASES

The operation in the Sarthe was code-named Headmaster.

SOE F Section Personnel

The operation in Thailand was code-named Coupling.

Our senior Thai organizer was named Snoh Nilkamhaeng, code-named Chew.

I used my real name and code-name Michel and nickname Soapy. Hudson was too much for the Thais who called me Khun (Mr) Sun!

INTRODUCTION

When my father was about 22 years old he became ill with TB, or consumption, as it was termed in those days. His worried family despatched him on a round-the-world cruise with stopovers at various places in the Antipodes. Apparently it took him about a year. When he got back his family were alarmed to see that he looked iller than ever. The doctor diagnosed his TB as being in the last stages and informed him that he had six months to live, adding that if he would take a cure in Switzerland he might last a year! Opting for a year rather than six months he moved to Arosa at that time famous for its sanatoria and at the end of the year minus one lung he was cured of TB and subsequently lived to age 73! He decided, nevertheless, to live in Switzerland and met my mother while she was holidaying with her family in Arosa. They were married, I was born and we lived in Montreux where my fathers business was centred. Of course everything was interrupted by the outbreak of the First World War in August, 1914. We hurriedly returned to Britain and settled down temporarily in Eastbourne, in a large house belonging to my grandfather. At the age of four I can remember my uncles in army officers uniform and my aunts as VAD nurses. My mother was head cook in a hospital and my father, unable to pass a medical for active service, worked in a convalescent soldiers camp. However, neither of these two latter occupations lasted long as my father, with his knowledge of languages and connections with Switzerland was posted as a Vice-Consul to the Legation in Montreux. We travelled via Lyon and I well remember seeing an enormous review of French soldiers from our hotel window. It was the spring of 1916 and, I suppose, was intended to be a morale-boosting exercise. The losses on the Western front were piling up and the population was already under pressure.

Everything seemed relatively peaceful in Switzerland. True, food was apparently rationed, but at the age of six this was the least of my worries! There were quite a number of Allied soldiers who had been wounded and, by international agreement, interned in the French-speaking canton of Vaud. Among them was a Belgian cousin of my family who had been badly wounded in the head and lost an eye. He was a jolly person, in spite of his injuries, and after the war became a monk.

I was given French lessons and, playing with Swiss children, soon began to converse happily with them. After about a year in Montreux my father was transferred to St Gallen in German Switzerland where his duties involved reading the newspapers printed in Germany and questioning persons who had come from that country. All with a view to gleaning any information which might be useful to the British Intelligence services operating through the Legation in Berne.

Shortly after arriving in St Gallen I contributed to my parents other worries by becoming extremely ill with bronchitis. When I finally recovered it was in a somewhat enfeebled state and the doctor considered that mountain air would be good for me. My mother and I were installed at fathers one-time place of cure Arosa. We stayed there until the end of the war. Of course, because the area was German-speaking the interned, wounded prisoners of war, were German. They were in uniform and we looked at them rather askance, but they seemed harmless enough!

Our stay in Arosa was uneventful enough except for one curious personal psychological phenomenon. I was now eight years old and was, I suppose, externally fairly normal. Unknown to my parents, perhaps related to my spell of bronchitis, I had two secret terrors. One was that mountains neighbouring Arosa would fall on us they were actually miles away. My other terror was that the hotel in which we lived would go on fire. Both these terrors, unspoken but real enough to me, vanished completely when we left Arosa at the end of the war.

It was May 1919. My fathers job as Vice-Consul had come to an end; he had become a correspondent of the Morning Post and had also set up an English language weekly The English Herald Abroad. His office was in Montreux. There was a considerable number of Britons living in Switzerland in those days. They had their own grocer, Mr Whitely, and their own tailor, Mr Moore. I can remember the latter providing me with a plus-four suit very smart and typically British.

We lived in Villars-sur-Ollon. From there my father could easily commute to Montreux and it provided a marvellous Alpine environment. We lived contentedly there for two decades. It was a particularly good place for summer and winter sports. I played golf and tennis in the summer with occasional interludes for mountain climbing. In the winter I skied and played ice hockey. All of this obviously left me little time for any educational studies!

During all these years I was subject to two contrasting influences. My family was British and we spoke English at home and I was brought up with English history and literature. Once out of the house, however, my environment was totally Frenchspeaking except for a couple of months of the year. In December the British arrived for the winter sports. For a few weeks I became quite friendly with some of them but of course they went home when their holidays were over.

When I was about 18 years of age my father started to develop an agency for importing British goods into Switzerland. I joined him in this and I gradually became quite interested in the business.

In summary I can say I was bi-lingual, was friendly with people from many walks of life but had no real friends. Sometimes this saddened me a little when I thought of it. In time I grew accustomed to a situation which made me something of a loner.

Next page