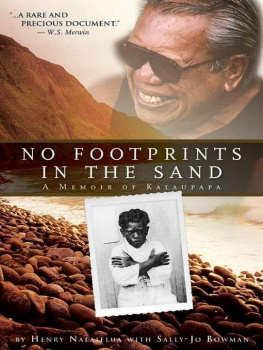

Most of the experience of those who have been afflicted with leprosy in Hawaiithe anguish and bereavement, and also the hope and loves and couragehas never been told. A truly personal account from within that history is a rare and precious human document. We are all indebted to Henry Nalaielua for the intimacy and candor of this narrative, and to Sally-Jo Bowman, who helped to bring it into words.

W.S. Merwin , Pulitzer Prize For Poetry ( The Carrier of Ladders )

Henry Nalaielua is surely a kupuna of the centuries, whose aloha is unconditional, even through times of escalating changes for Native Hawaiians. A historian, storyteller, composer, musician, singer, artist, diplomat and politically savvy health care advocatethis is how I know Uncle Henry. No Footprints in the Sand will now be woven into our historyfor all who call Hawaii home. A must read for Hawaii health care providers.

Emmett Aluli , Molokai physician

No Footprints in the Sand is the inspiring story of a life well lived despite physical affliction, separation from family, the injustice of exile. Henry Nalaielua has faced the challenges of that life with courage, honesty, dignity, and unfailing good humor. In the whole history of Kalaupapa there have been but a handful of books by, or about, the ordinary people who lived and died on that painful shore. No Footprints in the Sand ranks among the best.

Alan Brennert , Molokai

NO FOOTPRINTS

IN THE SAND

A M EMOIR OF K ALAUPAPA

NO FOOTPRINTS

IN THE SAND

A MEMOIR OF KALAUPAPA

BY HENRY KALALAHILIMOKU NALAIELUA

WITH SALLY-JO KEALA-O-ANUENUE BOWMAN

2006 Moolelo Aina LLC

3rd Printing

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information retrieval systems, without prior written permission from the publisher, except for brief passages quoted in reviews.

ISBN 978-0-9779143-0-2

ISBN 978-0-9844212-3-7 (Amazon Kindle format)

ISBN 978-0-9844212-4-4 (.epub electronic format)

Library of Congress Control Number:

2006932700

D ESIGN

Jayson Harper

Darin Isobe

Lora Lamm

PacificBasin Communications

P RODUCTION

Maggie Fujino

E DITOR

Tamara Leiokanoe Moan

C OVER PHOTOGRAPHY

Monte Costa

Hawaii State Department of Health (inset)

B ACK COVER PHOTOGRAPHY

Ray Jerome Baker/Bishop Museum

All paintings by Henry Nalaielua,

reproductions courtesy of

Kaohulani McGuire and Lianne Sing

Additional photos courtesy of

Anwei Law Skinsnes, IDEA

Watermark Publishing

1088 Bishop Street, Suite 310

Honolulu, HI 96813

Toll-free 1-866-900-BOOK

www.bookshawaii.net

sales@bookshawaii.net

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3

Printed in the United States

Contents

For Gena

Prologue

Kalaupapa 2010

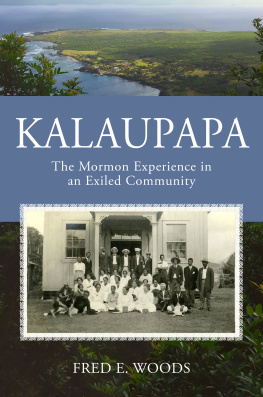

This wind-beaten peninsula off the rugged north coast of Molokai juts into wild seas, bounded at its back by cliffs nearly 2,000 feet high. The elements dominateocean, sky, wind, rain, the cycles of the sun by day and year, the stars and moon by night. In the absence of much civilization, its easy to feel the natural power of the earth. Todays visitors often remark on the peace and serenity of the place, rare qualities in the twenty-first century.

But this small triangle of land is known more for its historical sorrow as Hawaiis leper settlement, though it also has another history long predating that. Since 1984 it has been both a Hawaii State Health Department facility and a U.S. National Historical Park, with park access limited to guided tours.

Henry Kalalahilimoku Nalaielua, Jr. lived in this place nearly all of his long life. He spent only his first ten years with his family. His parentsHenry Sr., half-Hawaiian and half-Chinese, and Annie Helela Nalaielua, three-fourths Hawaiian and maybe part Tahitianhad Henry and five older children. When Henry was diagnosed with Hansens disease in 1936, the news was a virtual death sentence to a prison from which there would be neither escape nor parole. The crime: Leprosy. The ultimate prison: Kalaupapa.

In 1866 the first shipment of patients arrived at Kalaupapa under the new Hawaiian Kingdom quarantine law that tried to address the burgeoning epidemic that affected mostly native Hawaiians. Until the mid-twentieth century, health authorities insisted the disease was virulently contagious. Every experimental treatment came to naught. For those reasons, almost no patients ever returned from the Settlement.

For many decades, the disease was called by its Biblical name, leprosy. Now its called Hansens disease. Since the late 1940s modern antibiotic drugs have controlled or cured it. And medical researchers have discovered its not nearly so contagious as people used to think.

In the century of sorrow, more than 8,000 patients came to the Settlement. The last new patients arrived in 1969.

The Settlements population peaked in 1890 at 1,213, a figure that included kokua , or healthy individuals who came voluntarily with family members diagnosed with the disease. Some 8,000 are buried in the seaside graveyard or near the churches. Now Kalaupapas population is less than 100. Fewer than 20 are patients, the rest medical professionals or other service personnel. With more historic buildings than people, Kalaupapa is a ghost town in the making.

When Henry came here as a kid of 15after 5 years in Kalihi Hospital, a Hansens disease quarantine station on Oahuit was bigger than most shoreline villages in Hawaii, and not unlike them in many ways. But he couldnt help but notice one big difference.

The sand beach that stretches nearly a mile beyond the wharf was always laid smooth by the tide. Hansens disease plays havoc with feet, ulcerating them, crippling them. Such feet walk poorly. And in sand they cannot walk at all. Most patients in Henrys time left no footprints in that golden sand. In a few more years, he would be among those unable to walk the beaches.

Henry, born in 1925, was 80 when we finished his story. The oldest patients then were 99, the two youngest, 63. Soon the Settlement will be nothing but history.

I first met Henry in 1993, when we both happened to be staying overnight as guests of Dr. Emmett Aluli at his Hawaiian Homestead home near Hoolehua on topside Molokai. I was working on a magazine project with Emmett. Henry had attended meetings of a health board on which he sat with the doctor, and would fly down to Kalaupapa the next morning.

Fortunately I took Henrys address and phone number, because two years later I needed him. In 1995 I got two magazine assignments to write about Kalaupapa. The person I thought would be the key to spending extended time there was not available. Henry was my long shot. Would he remember me? Would he be receptive?

I called, establishing who I was in my family in that classic Hawaiian way reminiscent of our forebears reciting their genealogies at first meeting. I knew that, because of many regulations, most visitors to Kalaupapa spend only four hours there. I told Henry that to do a proper job of my assignments I would need two or three days at Kalaupapa. And I would need to bring Honolulu photographer Monte Costa with me.

A silence followed on the phone. I was thinking, If he doesnt help me, Ill have to tell those editors I promised them stories I cant produce.